U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

| < Previous | Table of Content | Next > |

No single design feature can ensure that a streetscape will be attractive to pedestrians. Rather, the best places for walking combine many design elements to create streets that "feel right" to people on foot. Street trees, separation from traffic, seating areas, pavement design, lighting, and many other factors should be considered in locations where pedestrian travel is accommodated and encouraged. This lesson provides an overview of these design elements, with examples of successful streetscapes throughout the United States.

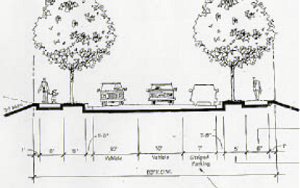

All urban sidewalks require the following basic ingredients for success: adequate width of travel lanes, a buffer from the travel lane, curbing, minimum width, gentle cross-slope (2 percent or less), a buffer to private properties, adequate sight distances around corners and at driveways, shy distances to walls and other structures, a clear path of travel free of street furniture, continuity, a well-maintained condition, ramps at corners, and flat areas across driveways. Sidewalks also require sufficient storage capacity at corners so that the predicted volume of pedestrians can gain access to and depart from signalized intersections in an orderly and efficient manner.

For two people to walk abreast, 5 feet is the bare minimum for sidewalk width. |

Sidewalks require a minimum width of 5.0 feet if set back from the curb or

6.0 feet if at the curb face. Any width less than this does not meet the minimum

requirements for people with disabilities. Walking is a social activity. For

any two people to walk together, 5.0 feet of space is the bare minimum. In

some areas, such as near schools, sporting complexes, some parks, and many

shopping districts, the minimum width for a sidewalk is 8.0 feet. Thus, any

existing 4.0-foot-wide sidewalks (permitted as an AASHTO minimum) often force

pedestrians into the roadway in order to talk. Even children walking to school

find that a 4.0- foot width is not adequate.

The desirable width for a sidewalk is often much greater. Some shopping districts require 12, 20, 30, and even 40 feet of width to handle the volumes of pedestrian traffic they encounter. Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. has 30-foot sidewalk sections to handle tour bus operations, K Street in Washington, D.C. has 20-foot sections to handle transit off-loading and commercial activity, the commercially successful Paseo de Gracia boulevard in Barcelona, Spain has 36 to 48 feet in most sections.

Designers must pay close attention to minimums, and only use variances below these levels for short sections. On the other side of the width equation, overly ample sidewalk widths are rarely justified. It is essential to work out the peak volumes of transit discharge, the likely commercial appeal of an area, and the influence of large tour buses and other factors when designing public space. Chapter 13 of the Highway Capacity Manual covers the topics of sidewalk width and pedestrian level of service.

Including ammenities such as newspaper stands and kiosks along corners creates lively, more defined spaces; however, they should not interrupt the flow of pedestrian traffic. |

Be sure to calculate the commercial need for outdoor cafes, kiosks, corner gathering spots, and other social needs for a sidewalk. Sidewalk widths have not been given sufficient attention by most designers. When working in a commercial area, designers should always consult property owners, chambers of commerce, and landscape architects to make certain that the desired width is realistic. Corner or mid-block bulb-outs can be used to their advantage for creating both storage space for roadway crossings and for social space.

The safety needs of motorists and bicyclists in the roadway must be considered when determining the desirable widths of adjacent sidewalks. There is compelling evidence that generous lane width (12- foot) standards applied to downtown and commercial streets are counterproductive and lead to faster traffic.

AASHTO specifically permits 10- or 11-foot travel lanes on arterials in commercial districts, and also permits turning lanes to be restricted to 10 feet. Truck volumes and the volume of bicycles must also be factored into this equation. As a general rule, when speeds are at or near bicycle speeds (15 to 20 mph), then bike lanes may not be as essential as the appropriate width of sidewalk. The designer is reminded that in Central Business Districts (CBD), the pedestrian volume may be 50 to 90 percent of total traffic. When these needs are not met, the commercial and social success of the community is lessened, and safety may be compromised.

Although most sidewalks are made of concrete, in some instances, asphalt can provide a useful surface. On trails, joggers and some others prefer asphalt. As a general rule, however, the long life of concrete, and the distinct pattern and lighter color are preferred. Paver stones can also be used, and in some applications, they have distinct advantages (see section later in this lesson).

A border area should be provided along streets for the safety of motorists and pedestrians as well as for aesthetic reasons. The border area between the roadway and the right-of-way line should be wide enough to serve several purposes, including provision of a buffer space between pedestrians and vehicular traffic, sidewalk space, snow storage, an area for placement of underground utilities, and an area for maintainable esthetic features such as grass or other landscaping. The border width may be a minimum of 5 feet, but desirably, it should be 10 feet or wider. Wherever practical, an additional obstaclefree buffer width of 12 feet or more should be provided between the curb and the sidewalk for safety and environmental enhancement. In residential areas, wider building setback controls can be used to attain these features. (AASHTO, A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways & Streets, 1990)

The preferred minimum width for a nature strip is 5 to 7 feet. A nature strip this wide provides ample storage room for many utilities. The width provides:

A tree set back from the roadway 4.0 feet meets minimum AASHTO standards for fixed objects when a barrier curb is used (30 mph or less), and is adequate for most species. The area is ample for most snow storage. When this preferred minimum cannot be achieved, any width, down to 4.0 feet or even 2.0 feet, is still beneficial.

The width of a natural buffer provides the essential space needed for situations such as protecting pedestrians from out-of-control vehicles. |

Nature strips, especially in downtown areas, may be a good location to use paver stones for easy and affordable access to underground utilities. In downtown areas, nature strips are also a convenient location for the swing-width of a door, for placement of parking meters, hydrants, lampposts, and other furniture.

Another way to achieve border width and the needed buffer from traffic is to provide bike lanes. This 5-foot space creates a minimal safe width to the sidewalk, even when at the back of the curb; reduces the effects of noise and splashing; and provides a higher level of general comfort to the pedestrian.

On-street parking has two distinct advantages for the pedestrian. First, it creates the needed physical separation from the motorist. Second, on-street parking has been shown to reduce motorist travel speeds. This creates an environment for safer street crossings.

On the back side of sidewalks, a minimum width buffer of 1to 3 feet is essential. Without such a buffer, vegetation, walls, buildings, and other objects encroach on the usable sidewalk space. With just several months of growth, many shrubs will dominate a sidewalk space. This setback is essential, not only to the walking comfort of a pedestrian, but to ensure essential sight lines at each residential and commercial driveway.

Pedestrians require a shy distance from fixed objects, such as walls, fences, shrubs, buildings, parked cars, and other features. The desired shy distance for a pedestrian is 2.0 feet. Allow for this shy distance in determining the functional width of a sidewalk.

Note that attractive windows in shopping districts create momentary stoppage of curious pedestrians. This is a desired element of a successful street. These window watchers take up about 18 to 24 inches of space. The remaining sidewalk width will be constrained. This is often desirable on sidewalks not at capacity. But if this stoppage forces pedestrians into the roadway, the sidewalk is too narrow.

Parked cars can also serve as a buffer between the sidewalk and the street. |

Newspaper racks, mail boxes, and other street furniture should not encroach into the walking space. Either place these items in the nature strip, or create a separate storage area behind the sidewalk, or in a corner or mid-block bulb-out. These items need to be bolted in place.

Parking meters on a narrow sidewalk create high levels of discomfort. In a retrofit situation, place meters at the back of the walk, or use electronic parking meters every 50 or 100 feet.

Parking garages on commercial district walks are ideally placed away from popular walking streets. If this cannot be done, keep the driveways and curb radii tight to maximize safety and to minimize the discomfort to pedestrians.

If possible, grade should be kept to no more than 5 percent, and, terrain permitting, avoid grades greater than 8 percent. When this is not possible, railings and other aids can be considered to help elder adults. The Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) does not require designers to change topography, but only to work within its limitations and constraints. Do not create any man-made grade that exceeds 8 percent.

Since falls are common with poorly designed stairs, every effort should be made to create a slip-free, easily detected, well-constructed set of stairs. The following principles apply: Stairs require railings on at least one side, and they need to extend 18 inches beyond the top and bottom stair. When an especially wide set of stairs is created, such as at transit stations, consider rails on both sides and one or two in mid-stair areas. Avoid open risers, and use a uniform grade with a constant tread to rise along the stairway length. All steps need to be obvious. Stairs should be lit at night. A minimum stairway width is 42 inches (to allow two people to pass). The forward slope should be 1 percent in order to drain water. Stairs in high nightlife pedestrian centers can be lit both above and at the side.

"Landscaping should be provided for esthetic and erosion control purposes in keeping with the character of the street and its environment. Landscaping should be arranged to permit sufficiently wide, clear, and safe pedestrian walkways. Combinations of turf, shrubs, and trees are desirable in border areas along the roadway. However, care should be exercised to ensure that guidelines for sight distances and clearance to obstructions are observed, especially at intersections." (AASHTO, A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways & Streets, 1990)

Landscaping can also be used to partially or fully control crossing points of pedestrians. Low shrubs in commercial areas and near schools are often desirable to channel pedestrians to crosswalks or crossing areas. Sidewalks must be graded and placed in areas where water will not pond or where large quantities of water will not sheet across.

Sidewalks along rural roadway sections should be provided as near the right-of-way line as is practicable. If a swale is used, the sidewalk should be placed at the back of the swale. If a guardrail is used, the sidewalk must be at the back of the guardrail. There will be times in near-urban spaces where the placement of sidewalks is not affordable or feasible. Wide paved shoulders on both sides of the roadway will be an appropriate substitute in some cases. However, the potential for growth in near-urban areas requires that rights-of-way be preserved. When sidewalks are placed at the back of the right-of-way, it may be necessary to bring the walkways forward at intersections in order to provide a roadway crossing where it will be anticipated by motorists. Security issues are also important on rural area sidewalks, so street lighting should be given full consideration. This lighting can act as part of the transitional area alerting higher speed motorists that they are arriving in an urban area.

Bridge crossings are essential to pedestrians and bicyclists. Whenever possible, the sidewalks should be continued with their full width. Sidewalks on bridges should be placed to eliminate the possibility of falling into the roadway or over the bridge itself. Sidewalks should be placed on both sides of bridges. Under extreme conditions, sidewalks can be used on one side only, but this should only be done when safe crossings can be provided on both ends of the bridge. When sidewalks are placed on only one side, they should be wider in order to accommodate large volumes of pedestrian traffic.

Management of land on the corner is essential to the successful commercial street. This small public space is used to enhance the corner sight triangle; to permit underground piping of drainage so that street water can be captured on both sides of the crossing; to provide a resting place and telephone; to store pedestrians waiting to cross the roadway; and to provide other pedestrian amenities. Well-designed corners, especially in a downtown or other village-like shopping district can become a focal point for the area. Benches, telephones, newspaper racks, mailboxes, bike racks, and other features help enliven this area. Corners are often one of the most secure places on a street. An unbuilt corner, in contrast, is often a magnet for litter and it erodes the aesthetics of the street.

For

both safety and security reasons, most sidewalks require street lighting.

Lighting is needed for both lateral movement of pedestrians and for detection

by motorists when the pedestrian crosses the roadway. As a general rule, the

normal placement of street luminaries, such as cobra heads, provide sufficient

lighting to ensure pedestrian movement. However, in commercial districts,

it is often important to improve the level of lighting, especially near ground

level. Successful retail centers often use low street lamps in addition to

or in lieu of high angle lamps. Some designs permit both the high angle highway

lamp and the low angle street lamp on the same pole.

For

both safety and security reasons, most sidewalks require street lighting.

Lighting is needed for both lateral movement of pedestrians and for detection

by motorists when the pedestrian crosses the roadway. As a general rule, the

normal placement of street luminaries, such as cobra heads, provide sufficient

lighting to ensure pedestrian movement. However, in commercial districts,

it is often important to improve the level of lighting, especially near ground

level. Successful retail centers often use low street lamps in addition to

or in lieu of high angle lamps. Some designs permit both the high angle highway

lamp and the low angle street lamp on the same pole.

Pedestrians on a pedestrian-oriented street design (shopping district) require three sources of lighting. The first is the overall street lighting, the second is the low placement of lamps (usually tungsten) that reach between and below most trees, and the third is the light emitted from stores that line the street. The omission of any one of these lights can result in an undesirable effect, and can reduce the desire to walk or shop at night.

Lights are needed in all areas where there are crosswalks or raised channel islands. Lighting can be either direct or can be placed to create a silhouette effect. Either treatment aids the motorist in detecting the pedestrian.

Pedestrians are less attracted to a commercial zone, or any area where there are dark spots. The potential to be victimized keeps many pedestrians from traveling through an area at night. Thus, lighting from shops, street lamps, and highway luminaries are essential to the success of a commercial district. Even one dark spot along a block may force some pedestrians to the opposite side of the street.

Pedestrians on a pedestrian-oriented street (shopping district) require three sources of lighting. |

Sidewalks are recommended on both sides of all urban arterial, collector, and most local roadways. Although local codes vary, AASHTO and other national publications insist that separation of the pedestrian from motorized traffic is an essential design feature of a safe and functional roadway.

Although the AASHTO Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (Greenbook) does not fully address the issue of sidewalk placement, in lightly developed areas, the Greenbook does recommend that rights-of-way be preserved on all arterial and collector roadways. Although AASHTO and many other organizations suggest that some short sections of local streets can have sidewalks on one side only, the designer should consider that single-side sidewalks can create unwanted motorist/pedestrian conflicts.

Many communities, such as Tallahassee, Florida, have small ($250,000), but significant, sidewalk construction funds set aside for community development and pedestrian safety. When prioritizing missing sidewalks, it is important to provide sidewalks to fill gaps on arterials and collectors at the following locations:

A typical neighborhood lot sidewalk of 5 feet and two street border trees raise the cost of the undeveloped lot by 1to 3 percent. In comparison, residential lot streets with sidewalks and trees often show an increased property value of $3,000 to $5,000.

The above discussion provides a basis for meeting the most basic needs of a pedestrian. In many parts of a city, it is essential to create highly successful walking corridors. The following elements are often found to be desirable to achieve robust commercial activity and to encourage added walking versus single-occupant motor vehicle trips. One or two very attractive features create a highly successful block ... and one or two highly offending or unsafe conditions will leave one side of the street nearly vacant.

It is hard to imagine any successful walking corridor fully void of trees. The richness of a young or mature canopy of trees cannot be matched by any amount of pavers, colorful walls or other fine architecture, or other features. Although on higher speed roads (40 mph and above) trees are often set at the back of the sidewalk, the most charming streets are those with trees gracing both sides of a walkway. This canopy effect has a quality that brings pedestrians back again and again. If only one side can be achieved, then on low-speed roadways, again the trees are best if placed between the walkway and the curb. A 4-foot setback from the curb is required.

In older pre-WW II neighborhoods, trees were often placed every 25, 30, or 35 feet apart. It is essential to keep trees back far enough from the intersection to leave an open view of traffic. With bulb-outs, this can often allow trees near the corner.

The designer of this pre-WW II neighborhood in Birmingham, AL knew the value of street trees. |

Colorful brick, stone, and even tile ceramics are often used to define corners, to create a mood for a block or commercial district, or to help guide those with visual impairments. These bricks or pavers need to be set on a concrete pad for maximum life and stability.

Paver stones can also be used successfully in neighborhoods. Denmark is one of many European countries that use concrete 1-meter-square paver stones as sidewalks. These stones are placed directly over compressed earth. When it is time to place new utilities, or to make repairs, the paver stones are simply lifted, stacked, and replaced when the work is complete.

Retail shops should be encouraged to provide protective awnings to create shade, protection from rain and snow, and to otherwise add color and attractiveness to the street. Awnings are especially important in hot climates on the sunny side of the street.

There are many commercial actions that can help bring back life to a street. Careful regulation of street vendors, outdoor cafes, and other commercial activity, including street entertainers, help enliven a place. The more activity, the better. One successful outdoor cafe helps create more activity and, in time, an entire evening shopping district can be helped back to life. When outdoor cafes are offered, it is essential to maintain a reasonable walking passageway. The elimination of two or three parking spaces in the street and the addition of a bulbed-out area can often provide the necessary extra space when cafe seating space is needed.

Alleys can be cleaned up and made attractive for walking. Properly lit and planned they can be secure and inviting. Some alleys can be covered over and made into access points for a number of shops. The tasteful and elegant Bussy Place alley in Boston was a run-down alley between buildings. With a roof overhead and a colorful interior with escalators, this alley is now the grand entry to a number of successful downtown shops. Other alleys become attractive places for outdoor cafes, kiosks, and small shops.

Victoria, on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, has a host of 30 or more alleys that channel a major portion of its pedestrian traffic between colorful buildings and quaint shops. Some alleys that were originally hard-wood bricks are now polished and provide a true walk through history.

The expansion of a mid-block set of crossings can help make these alleyways a prime commercial route and can lessen some of the pedestrian activity on several main roads.

Small tourist centers, navigational kiosks, and attractive outlets for other information can be handled through small-scale or large-scale kiosks. Well-positioned interpretive kiosks, plaques, and other instructional or historic place markers are essential to visitors. These areas can serve as safe places for people to meet and can generally help with navigation.

Public play areas and interactive art can help enliven a corner or central plaza. One especially creative linear space in Norway provided a fence and a 40- foot-long jumping box. Children were invited to see how far they could jump, and compare their jump with record holders, kangaroos, grasshoppers, dogs, and other critters.

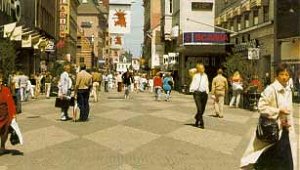

A number of European cities are reclaiming streets that are no longer needed for cars. Cars still have access to many of these streets before 10:00 a.m. and after midnight. Other streets in both the East and West are being converted to transit and pedestrian streets (e.g., 15th Street Mall in Denver). These conversions need to be made with a master plan so that traffic flow and pedestrian movements are fully provided for. There are many streets in America that have been temporarily converted to pedestrian streets and later, following a lack of use, were then converted back to traffic. There are many instances where it is not possible to generate enough pedestrian traffic to keep a street "alive." Under these conditions, the presence of on-street auto traffic creates security for the pedestrian.

Alleys can be made attractive and can serve as access points to shops.

Many plazas constructed in the recent past have been too large and uncomfortable for pedestrians, serving more to enhance the image of the building on the lot. Some of these are products of zoning laws that encouraged plaza construction in exchange for increased building height. However, bonus systems haven't ensured that the "public space" will actually be a public benefit. Decisions have been based on inches and feet, instead of on activity, use, or orientation. The result has been a number of plazas with problems: some are windswept, others are on the shady side of buildings, while others break the continuity of shopping streets, or are inaccessible because of grade changes. Most are without benches, planters, cover, shops, or other pedestrian comforts. To be comfortable, large spaces should be divided into smaller ones. Landscaping, benches, and wind and rain protection should be provided, and shopping and eating should be made accessible.

Small protected spaces provide separation from noise and traffic. |

It has been demonstrated that no extra room should be provided. In fact, it is usually better to be a bit crowded than too open, and to provide many smaller spaces instead of a few large ones. It is better to have places to sit, planters, and other conveniences for pedestrians than to have a clean, simple, and "architectural" space. It is better to have windows for browsing and stores adjacent to the plaza space, with crosscirculation between different uses than to have the plaza serve one use. It is better to have retailers rather than offices border the plaza. And, finally, it is better to have the plaza be a part of the sidewalk instead of separated from the sidewalk by walls.

Where is the best place for a plaza? Plazas ideally should be located in places with good sun exposure and little wind exposure, in places that are protected from traffic noise and in areas that are easily accessible from streets and shops. A plaza should have a center as well as several sub-centers.

The planner should inventory downtown for spaces that can be used for plazas, especially small ones. Appropriate spaces include: space where buildings may be demolished and new ones constructed, vacant land, or streets that may be closed to traffic or may connect to parking.

New stores can sometimes be set back 8 to 10 feet from the street to allow plaza space in exchange for increased density

Some suggestions for planners and developers of plazas include the following:

In some European countries, streets have been turned over to pedestrians.

Choose an existing public space that currently does not encourage walking and redesign it to better accommodate pedestrians. Your plan should be developed at a conceptual level. You should prepare a plan view drawing with enough information to identify major existing features, proposed improvements, and impacts. Profile and cross-section view drawings are also helpful in presenting particular details required to construct your proposed improvements. Aerial photographs and U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps often provide a good background for overlaying proposed improvements.

Streets with a raised median will usually have lower pedestrian

crash rates.

Conduct a pedestrian capacity analysis for the Piedmont Park case study location (as described in Exercise 3.8 of Lesson 3) using procedures described in the Highway Capacity Manual. The four major park entrances, as indicated on the Site Location Map, should be evaluated to determine the pedestrian level of service (LOS). In order to conduct this evaluation, the following assumptions should be utilized:

Text and graphics for this lesson were derived from the following sources:

Florida Department of Transportation, Florida's Pedestrian Planning and Design Guidelines, 1997.

Oregon Department of Transportation, Oregon's Bicycle and Pedestrian Plan, 1995.

Richard Untermann, Accommodating the Pedestrian, 1984.

Wilmington Area Planning Council, Mobility- Friendly Design Standards, 1997.

For more information on this topic, please refer to:

AASHTO, A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways & Streets, 1990.

Institute of Transportation Engineers, Design and Safety of Pedestrian Facilities, 1998.

Office of Transportation Engineering and Development, Pedestrian Design Guidelines Notebook, Portland, OR, 1997

| < Previous | Table of Content | Next > |