U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

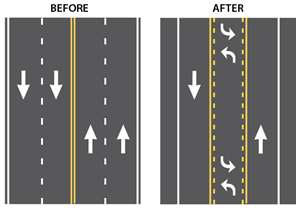

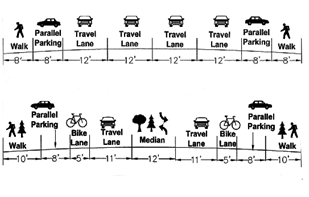

Road Diets reallocate travel lanes and utilize the space for other uses and travel modes. The most common type of Road Diet reduces the number of through lanes from four to two and adds a center two-way leftturn lane (TWLTL). Other uses for the reallocated space include

Example of a Road Diet

A painted center median with left-turn bays and pedestrian safety islands were installed along Luten Avenue from Amboy Road to Hylan Boulevard to calm traffic and enhance safety for all road users

This roadway configuration, incorporating a protected bike lane and a raised bus stop, could be achieved by implementing a Road Diet

This document describes the benefits and highlights real-world examples of agencies including Road Diets within new or revised transportation policies and guidance.

A single Road Diet project can yield numerous safety, operational, and multimodal benefits. Additionally, developing Road Diet-related policies and guidance – and therefore encouraging implementation on a large scale – can result in widespread advantages:

Improve Safety. Increasing Road Diet implementation can translate to more lives saved. An FHWA study1 found that converting a road from four to two though lanes with a center TWLTL can reduce overall crashes by 19 to 47 percent.

Save Time. Agency-standardized guidance or policy allows engineers to use an approved Road Diet template, framework, or set of design criteria that can jumpstart the design and implementation process. Non-standardized or "first time" designs tend to require more levels of management scrutiny and approval.

Save Money. Road Diets are already a relatively inexpensive countermeasure, but incorporating them into policies can provide the foundation for combining Road Diets with other efforts (e.g., resurfacing) to reduce costs further.

Increase Multimodal Use. Road Diets can raise property values and improve the "livability" of an area by reallocating space for bicycle or pedestrian facilities along a corridor. Systemic or wide-spread Road Diet implementation can create safer and more convenient pedestrian and bicyclist transportation networks.

Facilitate Public Acceptance. A Road Diet policy can build public confidence in the treatment. Such documentation can set a foundation for communication between the agency and the public and convey the Road Diet's benefits.

Many agencies across the United States have already incorporated Road Diets into their policies and guidance documents. Some developed standalone Road Diet documentation, while others chose to incorporate Road Diets into broader, pre-existing policies. The following sections provide examples of different types of Road Diet policy integration:

Standalone policies turn Road Diets into one of an agency's first-tier solutions. The following resources are examples of standalone Road Diet policies and guidance documents developed by State and local agencies.

Florida Department of Transportation's (FDOT) Statewide Lane Elimination Guidance2, 3, provides Road Diet and space reallocation guidance (referred to as lane eliminating). These documents include examples and impacts of Road Diets in Florida, a description of FDOT's Road Diet review process, and a discussion of issues associated with the improvement.

Maine Department of Transportation's (MaineDOT) Guidelines to Implement a Road Diet or Other Features Involving Traffic Calming4 provides Road Diet guidance for Maine municipalities. The document includes a brief overview of the treatment, Maine specific implementation guidance, an overview of the countermeasure's limitations, and a list of minimum study requirements.

Michigan Department of Transportation's (MDOT) Road Diet Checklist5 is a step-by-step list used by agency personnel when considering a Road Diet's appropriateness and applicability in a given situation.

St. Louis County's (Missouri) Road Diet Policy6 provides factors to consider when determining if a Road Diet is feasible for a location, including average weekly traffic (AWT) volumes, directional peak hour volumes, left turns, intersection impacts, alternate bypass routes, bus transit, bicyclists, and pedestrians.

Including Road Diets into an agency's Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP), overall transportation planning process, or design guidance distinguishes the countermeasure as a broader safety improvement strategy. The following are examples of how States have incorporated Road Diets into agency plans, guidance and practices.

Strategic Highway Safety Plans (SHSPs) can facilitate and promote Road Diets within an agency by incorporating the treatment into the agency's safety improvement approach. Several States refer directly to Road Diets in their SHSPs while others use a different name for the same improvement, including:

The table below lists State SHSPs that include Road Diets, the alternate terminology used, and the SHSP emphasis or focus area where it is discussed. All States' SHSPs can be found on FHWA's Office of Safety website.7

| State | Terminology | Emphasis or Focus Area |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Lane Conversion | Highways |

| Arkansas | Road Diet | Bicyclists, Pedestrians |

| District of Columbia | Road Narrowing | Pedestrian |

| Idaho | Lane Narrowing | Intersection |

| Michigan | Lane Conversion | Intersection |

| Minnesota | Road Diet | Bicyclists, Pedestrians |

| Missouri | Lane Narrowing | Intersection |

| New Jersey | Road Diet | Lane Departures, Bicyclists, Pedestrians |

| Ohio | Road Diet | Bicyclists, Pedestrians |

| Rhode Island | Road Diet | Achievements |

| South Dakota | Road Diet | Intersections |

| Washington | Road Diet | Bicyclists |

Many State and local agencies incorporate Road Diets into broader polices and guidance like design manuals, Complete Street plans, bicycle and pedestrian plans, or speed management and traffic calming plans. The legend below indicates the types of plans in which agencies have incorporated Road Diets for the following examples.

![]()

Incorporating Road Diets into resurfacing efforts can significantly reduce costs associated with the treatment. When a Road Diet includes shifting pavement markings within the existing right-of-way during a resurfacing project, internal planning and design costs are the only expenses incurred. Consequently, some State and local agencies have incorporated Road Diets into their routine review of all roads scheduled for repaving.

City of Oakland's Checklist for Complete Streets / Paving Project Coordination22 is completed for each roadway segment proposed for paving. Road Diets are one of the main elements considered on the checklist.

Rhode Island DOT23 recognized that during resurfacing and restriping, there would be no additional cost to alter pavement markings within the existing right-of-way to incorporate a Road Diet. They now plan their Road Diet installations as part of the overlay.

Seattle DOT24 monitors the city's resurfacing projects to see whether streets scheduled for upcoming roadway overlay projects are good candidates for Road Diets.

Virginia DOT's Northern District25 considers roads that are scheduled for repaving as opportunities to reallocate road space for bicycle lanes and other purposes before new pavement markings are installed.

Federal Highway Administration's (FHWA) Workbook for Building On-Road Bike Networks through Routine Resurfacing Programs26 assists communities in jump-starting their bicycle network development by utilizing Road Diets and capturing space reallocation opportunities as part of routine resurfacing.

A few State DOTs have either conducted research or partnered with universities to further their Road Diet policy development. Iowa, Kentucky, and Michigan DOTs used the findings from State-specific Road Diet studies to improve Road Diet guidance within their respective agencies.

Michigan State University's Safety and Operational Analysis of 4-lane to 3-lane Conversions (Road Diets) (2012)27 was developed for the Michigan Department of Transportation. The study examines the safety- and delay-related impacts of Road Diet conversions in Michigan. It includes guidelines for determining Road Diet feasibility based on ADT and peak hour volume. The study found that four- to three-lane Road Diet conversions could cause delays on roads with ADTs greater than 10,000 and peak hour volumes over 1,000. In almost all instances, crashes reduced after the Road Diet was implemented. This enabled researchers to develop a Michigan-specific Road Diet crash modification factor (CMF).

University of Kentucky's Guidelines for Road Diet Conversion (2011)28 was developed for the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. The study focused on evaluating and comparing the operation of three- and four-lane roads at signalized intersections. Out of the four Road Diets studied, three demonstrated a safety improvement. Based on this and other findings, the researchers developed operational and safety guidance targeted at helping agencies determine when a Road Diet conversion is appropriate, and increased their recommended maximum ADT threshold from 17,000 to 23,000. The guidance also provides suggested cross-section designs, recommendations for designing the transition to and from a Road Diet configuration, and a flow chart for determining appropriate implementation actions.

Iowa State University's Guidelines for the Conversion of Urban Four-Lane Undivided Roadways to Three-Lane Two-way Left-Turn Lane Facilities (2001)29 was developed for the Iowa Department of Transportation. During the study, researchers summarized previous research on Road Diet conversions located both throughout the United States and in Iowa, analyzed the operational impacts along an idealized conversion corridor, and provided guidelines for Road Diet conversion feasibility. Before-and-after crash results indicated that four- to three-lane Road Diets can increase safety without yielding a reduction in LOS. Based on the analysis, the researchers developed feasibility determination factors including roadway function, traffic volume, and LOS.

For more information about any of these resources or for technical assistance related to Road Diets, please contact FHWA's Road Diet Program Manager:

Rebecca Crowe

FHWA Office of Safety

(202) 507-3699

Rebecca.Crowe@dot.gov

Note: You will need the Adobe Reader to view the PDFs on this page.

1 FHWA "Evaluation of Lane Reduction 'Road Diet' Measures on Crashes." FHWA Report No. FHWA-HRT-10-053. (Washington, D.C: 2010) [ Return to note 1. ]

2 Florida Department of Transportation, Phase 1: Resource Document – Statewide Lane Elimination Guidance, February 2014. Available at: http://www.dot.state.fl.us/rddesign/CSI/Files/Lane-Elimination-Guide-Part1.pdf. [ Return to note 2. ]

3 Florida Department of Transportation, Statewide Lane Elimination Guidance, December 2014. Available at: http://www.dot.state.fl.us/rddesign/CSI/Files/Lane- Elimination-Guide-Part2.pdf [ Return to note 3. ]

4 Maine Department of Transportation, Guidelines to Implement a Road Diet or Other Features Involving Traffic Calming, April 2016. Available at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/road_diets/guidance/docs/maineDOTroad_diet.pdf [ Return to note 4. ]

5 Michigan Department of Transportation, "Road Diet Checklist," MDOT 1629 (02/15). Available at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/road_diets/guidance/docs/mdot_chklist.pdf. [ Return to note 5. ]

6 St. Louis County, MO, Department of Transportation, "St. Louis County Road Diet Policy," (St. Louis County, MO: September 2015). Available at: https://www.stlouisco.com/Portals/8/docs/document%20library/highways/publications/Road_Diet_Policy.pdf. [ Return to note 6. ]

7 FHWA. Office of Safety, "Web-links to State SHSPs" web page. Available at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/hsip/shsp/state_links.cfm [ Return to note 7. ]

8 AASHTO, Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities, 4th Edition (Washington, DC: 2012). This publication is available for purchase at: https://bookstore.transportation.org/item_details.aspx?ID=1943 or 1-800-231-3475. [ Return to note 8. ]

9 Charlotte Department of Transportation, Urban Street Design Guidelines, adopted October 22, 2007. Available at: http://charmeck.org/city/charlotte/Transportation/PlansProjects/pages/urban%20street%20design%20guidelines.aspx. [ Return to note 9. ]

10 Chicago Department of Transportation, Chicago Streets for Cycling Plan 2020 (n.d.). Available at: http://www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/cdot/bike/general/ChicagoStreetsforCycling2020.pdf. [ Return to note 10. ]

11 Scott, Beck, Rabidou. Complete Streets in Delaware: A Guide for Local Governments. (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Institute for Public Administration), prepared for the Delaware Department of Transportation. Available at: http://www.ipa.udel.edu/publications/CompleteStreetsGuide-web.pdf. [ Return to note 11. ]

12 City of Evansville, Indiana and the Evansville Metropolitan Plannng Organization, Evansville, Indiana Bicycle and Pedestrian Connectivity Master Plan (n.d.). Available at: http://www.evansvillempo.com/Docs/BikePed/Evansville_BPCMP_Final_Plan.pdf. [ Return to note 12. ]

13 Genessee County Metropolitan Planning Commission, Genesee County Complete Streets Technical Report (n.d.). Available at: http://gcmpc.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/Complete_Streets/Complete_Streets_Technical_Report_Approved_withAppendix.pdf. [ Return to note 13. ]

14 Los Angeles County, Model Design Manual for Living Streets (Los Angeles County: December 2011), funded by the Department of Health and Human Services through the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation. Available at: http://modelstreetdesignmanual.com/ model_street_design_manual.pdf. [ Return to note 14. ]

15 MnDOT Office of Traffic, Safety and Technology, Minnesota's Best Practices for Pedestrian/Bicycle Safety, Report No. 2013-22 (September 2013). Available at: http://www.dot.state.mn.us/stateaid/trafficsafety/reference/ped-bike-handbook-09.18.2013-v1.pdf. [ Return to note 15. ]

16 New York City Department of Transportation, Street Design Manual, Updated 2nd Edition, (New York: January 2016). Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/nycdot-streetdesignmanual-interior-lores.pdf. [ Return to note 16. ]

17 New York Department of Transportation, Engineering Division, Office of Design, Highway Design Manual, "Chapter 18, Appendix A - Capital Projects Complete Streets Checklist (18a-2)" (New York: 2015). Available at: https://www.dot.ny.gov/divisions/engineering/design/dqab/hdm/hdm-repository/chapt_18a.pdf [ Return to note 17. ]

18 Ohio Department of Transportation, Location & Design Manual Volume 1, "300 Cross Section Design," (Columbus, OH: January 2016). Available at: http://www.dot.state.oh.us/Divisions/Engineering/Roadway/DesignStandards/roadway/ Location%20and%20Design%20Manual/ Section_300_Jan_2016.pdf. [ Return to note 18. ]

19 Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Pennsylvania's Traffic Calming Handbook, Publication No. 383 (July 2012). Available at: http://www.dot.state.pa.us/public/PubsForms/Publications/PUB%20383.pdf. [ Return to note 19. ]

20 City of Salisbury Department of Land Management and Development and the NCDOT Divison of Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation, Salisbury Comprehensive Bicycle Plan, (Salisbury, NC: July 2009). Available at: http://www.salisburync.gov/Departments/CommunityPlanning/DevelopmentServices/ Documents/ SalBikePlan_FINALSUBMITTAL.pdf. [ Return to note 20. ]

21 Seattle Department of Transportation, "Road Diets", Seattle.gov. Accessed May 2016. Available at: http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/pedestrian_masterplan/pedestrian_toolbox/tools_deua_diets.htm. [ Return to note 21. ]

22 City of Oakland, City of Oakland Checklist for Complete Streets / Paving Project Coordination (unpublished). Available at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/road_diets/guidance/docs/oakland_chklist.pdf. [ Return to note 22. ]

23 For additional details and information, please contact Sean Raymond, Sean.Raymond@dot.ri.gov. [ Return to note 23. ]

24 For additional details and information, please contact Dongho Chang, Dongho.Chang@seattle.gov. [ Return to note 24. ]

25 For additional details and information, please contact Randy Dittberner, Randy.Dittberner@VDOT.Virginia.gov. [ Return to note 25. ]

26 Federal Highway Administration, Incorporating On-Road Bicycle Networks into Resurfacing Projects, FHWA-HEP-16-025 (Washington, DC: 2016). Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/publications/resurfacing/resurfacing_workbook.pdf. [ Return to note 26. ]

27 Lyles, R. W. , Safety and Operational Analysis of 4-Lane to 3-Lane Conversions (Road Diets) in Michigan, Michigan State University, RC-1555 (Lansing, MI: 2012). Available at: http://nacto.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/safety_and_operation_analysis_lyles.pdf. [ Return to note 27. ]

28 Stamatiadis, N. Guidelines for Road Diet Conversions, University of Kentucky, KTC-11-19/SPR-415-11-1F (Lexington, KY: November 2011). Available at: http://www.ktc.uky.edu/files/2012/06/KTC_11_19_SPR_11_415_1F.pdf. [ Return to note 28. ]

29 Knapp, K. K., et al. , Guidelines for the Conversion of Urban Four-lane Undivided Roadways to Three-lane Two-way Left-turn Lane Facilities, Center for Transportation Research and Education, CTRE Management Project 99-54 (Ames, IA: 2001). Available at: http://www.ctre.iastate.edu/reports/4to3lane.pdf. [ Return to note 29. ]

March 2016

FHWA-SA-16-074