U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

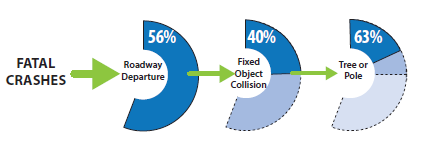

Roadway departures account for the majority of all fatal crashes occurring in the United States. In fact, 56 percent1 of fatal crashes fit the roadway departure definition: a crash which occurs after a vehicle crosses an edge line or a center line, or otherwise leaves the traveled way.2 Of this data set, 40 percent involved a collision with a fixed object.3 Roadside trees and utility poles comprise 63 percent of the fixed objects struck, making them the most harmful event in 14 percent of all fatal crashes.4

Given this overrepresentation, it is reasonable to suggest that managing roadside trees and utility poles would be common strategies to reduce fatal crashes; however most transportation agencies have indicated that they find it challenging to mitigate these obstacles.5 A few State departments of transportation (DOT) apply some level of roadside management in this area and their practices are examined here in greater detail.

Mitigating tree and utility pole-related crashes could significantly support States' efforts to reduce fatal crashes; however, these two roadside features are arguably the most elusive of all fixed objects to control for the following reasons:

Coupled with reduced maintenance and operations budgets and personnel within the DOTs, these reasons lead to tree removal and utility pole relocation becoming lower roadside management priorities.

Figure 2. Photo. Utility poles and trees in close proximity to the roadway.

A comprehensive investigation of roadside tree and utility pole management has consistently rated among the highest priorities of experts in roadside safety design. Problem statements pertaining to this subject matter, however, generally receive lower funding priority when presented to the transportation community at large, resulting in a shortage of available resources on the topic. This report is intended to provide agencies with examples of successful management practices until additional research is conducted. These practices range from complex, multi-million dollar contract solutions to in-house efforts that can be accomplished with minimal resources, and have been drawn from every region of the United States as well as from previous research.

It should be noted that measures taken to reduce or eliminate tree and utility pole-related crashes will vary based on many factors, including location (e.g., urban versus rural), proximity to traffic, appropriateness of certain countermeasures, and environmental and historical factors.

The practices described within this report are not all-inclusive; they are merely a snapshot of multiple methods gleaned from a cross-section of the industry. In a comprehensive roadway departure survey conducted by FHWA in 2014, States indicated their levels of engagement with all aspects of roadway departure, including crashes into trees, utility poles, and other fixed objects. Practices cited in this report were identified from the survey responses and through a limited literature review.

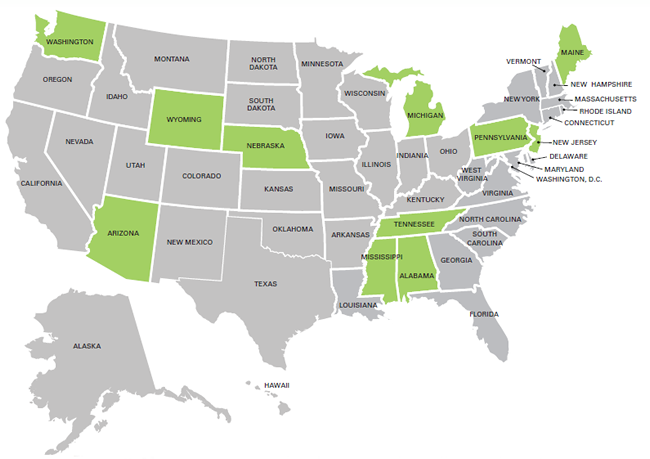

Figure 3. Map. Distribution of states with noteworthy roadside tree

and utility pole management practices.

Twenty-eight States and the District of Columbia responded to the survey. As a first pass, researchers selected the 15 States that responded to the tree and utility pole questions. They prioritized the States on this shortlist by applying a basic points system to the survey answers.

Although the survey results were useful to help identify States addressing these issues, the survey itself was somewhat limiting. Although most questions had an "other" option and offered the opportunity to explain, few States provided additional information. For the most part, respondents seemed constrained by the multiple choice format. However, even with the limitations of the survey, it was reasonable to assume that the States most responsive with tree and utility pole countermeasures would be the most likely to yield best practices.

To identify States with notable tree and utility pole management practices in addition to those participating in the survey, researchers conducted a limited literature review. This effort added an additional State to the draft list based upon a tree management program not disclosed within the survey.

Investigators were concerned, however, about the possibility of a best practice lying within a State that did not respond to the survey. For instance, neither a single State in New England nor a State in the Northern Mountain region answered a tree or utility pole question in the survey. Since these two regions are among the most densely forested in the country, it seemed likely that some best practice countermeasures would be present there. Through previous professional experience with, and additional literature search for this region, the team discovered the potential for additional best practices from a public-private partnership (P3) and an additional State.

Researchers conducted telephone interviews with officials in most of the states chosen from the survey, to learn about their tree and utility pole management practices in greater depth. One State submitted a written response to investigators and the team researched a few other resources independently.

There is a hierarchy of roadside safety countermeasures presented by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) "Roadside Design Guide" and generally accepted across the industry.7

For the purpose of this report, however, there are some significant differences that must be noted:

Therefore, the AASHTO hierarchy will be distilled down to the following categories of countermeasures, in line with the FHWA Roadway Departure Strategic Plan.8

Additionally, there are proactive and reactive measures that practitioners can implement to prevent or reduce tree and utility pole-crashes. Practices aligning with the three countermeasure categories above are presented as reactive in Chapter 2, as they are implemented or applied only after agencies have experienced crashes. Chapter 4 captures proactive practices that influence designs and mitigate safety concerns before they arise.

1 Federal Highway Administration, Office of Safety, "Roadway Departure Safety," 2010-2013 last modified September 1, 2015. Available at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/roadway_dept/.

2 Federal Highway Administration, FHWA Roadway Departure (RwD) Strategic Plan, (Washington, DC: March 2013), p.3.

3 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety Highway Loss Data Institute, "Roadway and Environment: Collisions with Fixed Objects and Animals," last modified, 2016. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/roadway-and-environment/fatalityfacts/fixed-object- crashes.

4 Ibid.

5 Unpublished results from a Roadway Departure Focus States Initiative survey conducted under FHWA contract DTFH61-10-D-00024, Task Order 12-003 in October 2014.

6 Neuman, T., et al, NCHRP Report 500: Guidance for Implementation of the AASHTO Strategic Highway Safety Plan, Volume 3: A Guide for Addressing Collisions with Trees in Hazardous Locations, Washington DC: Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, 2003, pp.I-3, I-4.

7 American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), Roadside Design Guide, 4th Edition, Washington, DC: AASHTO, 2011, pp.1-4.

8 Federal Highway Administration, FHWA Roadway Departure (RwD) Strategic Plan, (Washington, DC: March 2013), p.2.

9 FHWA, Center for Accelerating Innovation-Every Day Counts, "Safety EdgeSM," last modified: October 21, 2015. Available at: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/edc-1/safetyedge.cfm.

| < Previous | Table of Contents | Next > |