U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

U.S. Department of Transportation

December 2006

| < Previous | Table of Contents | Next > |

All visits were coordinated in advance with host agencies. Appendix C contains the set of amplifying questions provided in advance of the scan visits. The agenda and format for visits varied somewhat but typically included an entrance conference at the State DOT headquarters featuring an overview of the scan's purpose and scope by one of Scan Team cochairs. Representatives from FHWA Division Offices and DOT headquarters accompanied the Scan Team throughout the visits. The Scan Team met with personnel of DOT offices in all States, either at the district/region or central office. The involvement of project-level personnel provided useful insights into the development, design, and implementation of resurfacing projects. Additionally, the Scan Team met with county engineers in Washington State, New York, and Iowa. Appendix D includes the names and contact information for key contacts in host States and counties.

All transportation agencies have some similarities; yet, each is also distinctive. Climate, cultural, demographic, economic, governance, and terrain factors all influence the operating environment, mission, and methods of a transportation agency. A number of factors that shape an agency's operating environment and its performance related to the scan subject are discussed below.

There are insufficient resources to address either all pavement preservation needs or all safety needs. Therefore, allocating resources among pavement and safety needs is difficult for all agencies.

The degree of emphasis-and level of investment-agencies commit to incorporating safety improvements in resurfacing varies substantially, even among the States visited. The degree of discretion that agency leaders and individual professionals exercise also varies. For several State DOTs, the level of safety investment is determined at the State level. For example, DOTs in Washington State and Colorado are guided by agency-wide safety expenditure amounts.

The eligibility guidance used by the NYSDOT and PennDOT are less specific. Geometric improvements that are made as part of resurfacing are not necessarily attributed to a safety improvement fund.

For States with less specific and definitive guidance, agency decision makers at all levels exercise substantial discretion. Extensive safety investments were made in some programs and projects; in other cases, safety improvements were modest. The differences related to perceptions about needs and priorities.

Every agency endeavors to preserve its roadways and improve safety; however, not every agency pursues these goals through integrated processes. Incorporating safety improvements into resurfacing involves consideration of funding, priorities, observable results, delivery schedules, and tort liability issues). In the face of competing objectives, resource allocations must align with public priorities. The Scan Team noted that leadership is needed to force resolution of priorities among competing needs and to integrate separate functional domains (e.g., maintenance and safety bureaus). Leadership can also play a critical role in securing resources and determining eligibility. In the States visited, career professionals and executives have successfully developed and implemented programmatic approaches to balancing and integrating their pavement preservation and safety improvement goals.

The evolution and development of agency practices were discussed with several of the agencies visited. In some States, integration of safety into resurfacing is outlined in the DOT-FHWA Stewardship Agreement. In other cases, it was determined that an integrated strategy was the logical means to pursue two goals. Resurfacing is often the only improvement an agency will make to a road segment during a 5- to 20-year period. Therefore, resurfacing projects are the best (and perhaps only practical) opportunity to enhance safety. Mobilization, traffic control, and contract administration costs are not substantially increased by incremental contract items. Agency executives with cross-functional responsibilities, either Statewide or for a specific geographic area, were generally supportive of integrating safety into resurfacing.

DOT staffs in the States visited also tended to embrace both functions (i.e., pavement preservation and safety improvement) as inherent organizational responsibilities. For some agencies, the notion of integrating safety into pavement projects was deeply ingrained and unquestioned. Other agencies are in transition and working through the policy and technical issues related to making safety investments through a program with a traditional infrastructure focus.

"There might not be another DOT activity at the project location for another 10 years."

Paul Jesaitis

Project Development Engineer

Colorado DOT

Agencies have to account for resources and demonstrate progress toward established goals. All State DOTs visited had information systems related to infrastructure conditions (e.g., pavement management systems) and safety. Pavement-related measures include lane-miles paved, tons of asphalt placed, and ride quality (typically measured using the International Roughness Index). DOTs also have safety goals and plans. Example safety measures are crashes per reporting period (typically one year), crash rates, annual fatalities, fatal crash rates, pedestrian-involved crashes, pedestrian fatalities, and impaired driver-related crashes.

In general, agencies can readily relate pavement preservation investments to outcomes. The type and interval of resurfacing and restoration interventions are the dominant factors affecting pavement conditions. Conversely, the link between specific safety outcomes and investments is less certain. Reported safety statistics are influenced by many factors, such as legislation (e.g., seatbelt and helmet use, speed limits), enforcement efforts, weather patterns, and reporting thresholds. These factors, and the random nature of crashes, make it very difficult to isolate the effect of safety countermeasures, especially over short intervals (e.g., year-to-year) and at specific locations. Consequently, reported safety improvements are often stated in terms of investments and visible features. For example, agencies may report rumble strip installation (measured in units of length) as a measurable safety improvement. There is little doubt that rumble strips, in aggregate, prevent crashes and the associated consequences. However, it is a difficult and subjective exercise to estimate the number of fatalities and injuries averted by the installation of specific rumble strips during a reporting period. One agency safety manager indicated that the absence of clear safety investment-results relationships makes it difficult to attain additional resources.

During the scan, detailed measurement plans were observed in New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington State. PennDOT uses a business planning process and relevant parts of the two district business plans were reviewed during the scan. The plans tend to be outcome oriented and tied to the organization's global goals, which include specific safety objectives and maintenance outcomes. WSDOT has a rigorous reporting process and submits quarterly reports, known as Grey Notebooks to the Washington State Transportation Commission. These reports provide information on capital program expenditures, system performance and condition, safety, and a host of other measures. Pavement conditions are reported as the percent of pavements in good condition; for 2003, the level was at 90 percent. Washington State traffic fatalities and fatality rates are reported, along with a comparison to other States. Each of the States visited monitors and reports basic performance and results but the detail and frequency of reports varies substantially.

Resurfacing and pavement restoration projects are initiated with a primary purpose of improving roadway surface conditions and extending the utility of existing pavement structures. This is true in every State and county visited. NYSDOT also has a program to resurface roadways with high wet-road crash levels and low skid resistance. The role of Pavement Management Systems (PMS) in resurfacing project initiation varies by DOT. The UDOT uses its PMS to identify the next scheduled pavement intervention for every State-maintained road segment. This information is organized into a Plan for Every Section of Road and serves as the primary basis for the annual resurfacing program. In Colorado, each CDOT regional office identifies resurfacing project priorities. These priorities are reviewed by the central PMS section. The regional office and PMS section lists typically do not match identically and the two groups collaborate to develop a final list. The PMS section attempts to have 70 percent of its recommended mileage programmed. For most States, PMS condition data is one of several sources of information considered in developing the annual resurfacing program. The observations of maintenance personnel and input from the public and elected officials are also factors in programming projects. PMS includes extensive inventory data, including valuable safety management and project development information. PennDOT's PMS provides information on pavement edge drop-offs.

Pavement resurfacing and restoration strategies range from surface treatments to multicourse overlays. Several States use their PMS for preliminary identification of intervention alternatives. The final determination of a pavement strategy is typically based on field observations and, in some cases, materials testing and analysis. Superpave mixes are commonly used for overlays. Stone Matrix Asphalt mixes are used occasionally for resurfacing major routes in Washington State.

Inadequate pavement cross slopes and superelevation rates are often addressed in conjunction with resurfacing. Pavement edge drop-offs are typically, but not always, addressed with either shoulder backup or sloped pavement edges (e.g., Safety Edge).

Each agency has a unique approach to scoping and designing resurfacing and restoration projects. For transportation agencies, project development is a business process. As such, the project development process covers the assignment of roles, funding amounts and eligibility, timing of actions and schedules, and a host of technical guidance.

"Our process is a rational basis for reaching decisions without being unduly burdensome or paper intensive."

Bryan Allery

Traffic & Safety Engineer

Colorado DOT

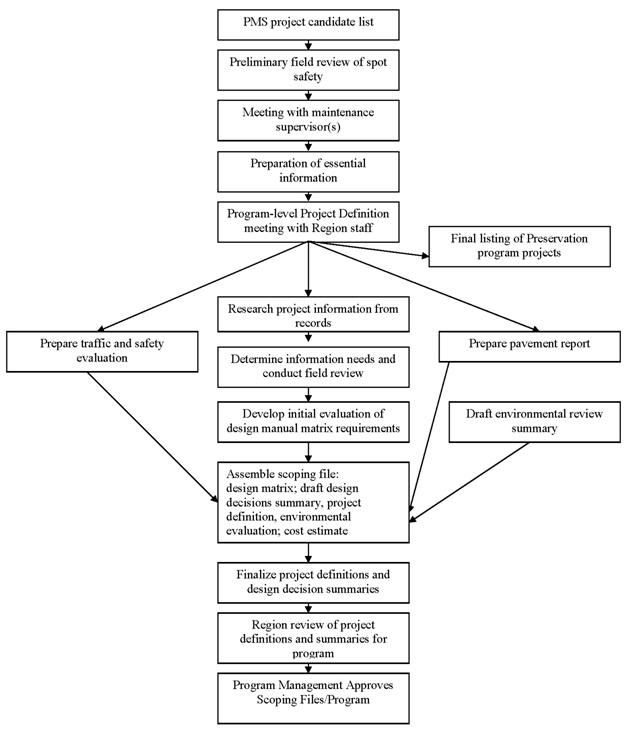

All State DOTs visited are decentralized organizations; however, the distribution of roles and responsibilities between headquarters and field offices varies from State to State. Agencies attempt to involve personnel with the necessary skills and perspectives and still deliver projects in a timely fashion. Nearly all Iowa and Pennsylvania resurfacing project development decisions are made by local DOT units (e.g., regions/districts). Colorado and Utah DOT Traffic and Safety headquarter personnel perform project safety analyses and develop recommendations. In the WSDOT process, headquarters develops design guidance and approves project definition (Program Management is a headquarters bureau). Figure 2 provides a simplified flow chart of WSDOT's pavement preservation project development process.

Figure 2. Simplification of WSDOT pavement preservation project development process.

Several agencies have different types of pavement restoration programs and distinct project development processes exist for each. For capital-funded 3R projects, PennDOT uses the project development process and criteria in its Design Manual. Less formal procedures, which vary by district, are employed for maintenance-funded projects. NYSDOT has project development guidance for each restoration program (i.e., 1R, 2R, nonfreeway 3R, freeway 3R). A series of factors (e.g., pavement needs, safety record, scope of improvement, right-of-way needs, impacts, controversy) are used to determine which program a specific project should be processed under. At the time of the scan, UDOT was developing a process diagram for resurfacing projects to be used in lieu of the current flow chart, which applies to all projects but is considered unnecessarily complex for resurfacing projects.

The specter of tort liability looms over every transportation agency. The influence of tort claims on resurfacing project decisions varies substantially among the agencies visited and is largely a result of the prevailing legal climate (e.g., statutory limits on the nature and magnitude of agency liability). In general, agency procedures and project-level documentation were viewed as an integral part of the agency's tort management strategy.

Numerous transportation agency personnel indicated concern about litigation and expressed the opinion that a litigious environment contravenes public interest. Several engineers expressed reluctance to make any geometric improvements unless all applicable criteria were attained. Several engineers expressed the opinion that simple resurfacing involves less tort exposure than projects that alter infrastructure but do not result in attainment of all applicable criteria. Even well-informed, well-considered, and well-documented deviations (e.g., design exceptions) are considered risky. Tort concerns were expressed most strongly in New York and Washington State.

Roadway infrastructure modification can trigger environmental processing and permitting requirements. Several transportation engineers indicated that the substantive environmental protection requirements were considered out-of-balance with seemingly minor impacts. Implementation of the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), Phase II Stormwater Program is particularly challenging. Various States indicated that NPDES implementation provisions discourage cross-section improvements (e.g., widening, paving shoulders). The time and staff effort needed to develop documentation and secure permits is at cross purposes with transportation agency goals of expedient project development and delivery.

The Scan Team observed several measures to manage the environmental process for resurfacing projects. CDOT includes environmental specialists on project teams and WSDOT is developing geographic information systems (GIS) overlays to identify environmentally sensitive areas (e.g., threatened and endangered species habitat, wetlands). Programmatic permits, where applicable, are very beneficial.

Compliance with the ADAAG is a major cost and organizational challenge for many agencies, including all State DOTs. The status of compliance and strategies for attaining compliance varies substantially among the States visited. As a result of litigation, the UDOT is developing an inventory of curb ramps along State highways that will be used to identify noncompliant facilities. After the inventory is complete, dedicated contracts will be let to install compliant curb ramps. CDOT provides ADA compliance measures in other projects, including resurfacing. A number of ADA measures were observed in CDOT resurfacing projects during the scan. When included in resurfacing projects, the cost of ADA compliance items is typically assessed to the same fund category.

| < Previous | Table of Contents | Next > |