U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Download Version

PDF [1.94 MB]

This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document.

The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement.

1. Report No. FHWA FHWA-FLH-10-0011 |

2. Government Accession No. |

3. Recipient’s Catalog No. |

|||

4. Title and Subtitle Road Safety Audit Toolkit for Federal Land Management Agencies and Tribal Governments |

5. Report Date September 2010 |

||||

6. Performing Organization Code |

|||||

7. Authors Dan Nabors, Kevin Moriarty, and Frank Gross |

8. Performing Organization Report No. |

||||

9. Performing Organization Name and Address Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. (VHB) |

10. Work Unit No. |

||||

11. Contract or Grant No. DTF61-05-D-00024 |

|||||

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Office of Safety |

13. Type of Report and Period Covered |

||||

14. Sponsoring Agency Code |

|||||

15. Supplementary Notes: This report was produced under the FHWA contract DTF61-05-D-00024. The Contracting Officer’sTechnical Manager (COTM) was Chimai Ngo, FHWA Office of Federal Lands Highway. The project team gratefully acknowledges the input provided by the following individuals over the course of this project: Jeff Bagdade, Mike Blankenship, Victoria Brinkly, Rebecca Crowe, Edward Demming, Peter Field, Thomas Fronk, Christoph Jaeschke, Salisa Norstog, Norah Ocel, Jennifer Proctor, Gerald Fayuant, Steve Suder, Dennis Trusty, and Scott Whiemore. |

|||||

16. Abstract Road Safety Audits/Assessments (RSAs) have proven to be an effective tool for improving safety on and along roadways. As such, the use of RSAs continues o grow throughout the United States. The success has led to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) including the RSA as one of its nine “proven safety countermeasures”. Federal Land Management Agencies (FLMAs) and Tribes are beginning to witness the benefits of conducting RSAs. However, FLMAs and Tribes often face unique conditions, staffing, and funding constraints that do not allow resources to be devoted to improving roadway safety. The “Road Safety Audit Toolkit for Federal Land Management Agencies and Tribal Governments” is intended to be used by FLMAs and Tribes to overcome these obstacles. Information, ideas, and resources are provided in key topic areas including how to conduct an RSA, common safety issues and potential improvements, establishing an RSA program, and incorporating RSAs into the planning process. The Toolkit serves as a starting point, providing information to FLMAs and Tribes about partnerships needed to build support, available funding sources for the program and improvements, tools to conduct RSAs, and resources to identify safety issues and select countermeasures. Worksheets and other sample materials have been provided to aid in the RSA process including requesting assistance, scheduling, analyzing data, conducting field reviews, and documenting issues and suggestions. Examples of programs and experiences of other agencies have also been included throughout to provide examples of successes and struggles in implementing RSAs and improving safety for all road users. |

|||||

17. Key Words Safety, Road Safety Audit, Toolkit, Federal Land Management Agencies (FLMAs), Tribes |

18. Distribution Statement No restrictions. This document is available to the public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161. |

||||

19. Security Classif. (of this report) Unclassified |

20. Security Classif. (of this page) Unclassified |

21. No. of Pages: 66 |

22. Price |

||

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72) - Reproduction of completed pages authorized

Road Safety Audits/Assessments (RSAs) are a valuable tool used to evaluate road safety issues and to identify opportunities for improvement. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) defines an RSA as a “formal safety performance evaluation of an existing or future road or intersection by an independent, multidisciplinary team.” RSAs can be used on any type of facility during any stage of the project development process.

RSAs examine roadway and roadside features that may pose potential safety issues.

Some element of safety is considered on every project. However, sometimes conditions on or adjacent to Federal and Tribal lands merit a more detailed safety review. For example, traffic volumes on a roadway may be higher than intended or may carry a higher percentage of trucks and other heavy vehicles due to unanticipated growth. These conditions can divide a Tribal community or interject a set of complexities to an unfamiliar visitor. RSAs examine these conditions in detail by pulling together a multidisciplinary team that looks at the issues from different perspectives – perspectives which are often not a part of a traditional safety review. RSAs also consider safety from a human factors point of view which aims to answer the following questions: How and why are people reacting to the roadway conditions? What do people sense and how do they react to those senses? What are the associated risks with those elements? The multidisciplinary team approach helps to answer these questions. Interactions between all road users (e.g., pedestrians and motor vehicles, commuter traffic and recreational vehicle traffic, bicycles and motor vehicles, etc.) are investigated to determine potential risk and to identify programs and measures to help reduce those risks and create safer environments for all road users.

Partner Agencies

RSAs have proven to be a leading tool for improving safety on and along roadways. As such, the use of RSAs continues to grow throughout the U.S. A decade ago, few states had experience conducting RSAs; now each state has had some experience with the RSA process. The success has led to FHWA including the RSA processas one of its nine “proven safety countermeasures.” Federal Land Management Agencies (FLMAs) and Tribes are beginning to witness the benefits of conducting RSAs. FHWA Federal Lands Highway (FLH) division offices have helped plan or conduct RSAs on facilities owned by the National Park Service (NPS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Forest Service (FS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and several Tribes. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has included RSA findings in planning and programming documents. Western Federal Lands Highway Division (WFLHD) has used RSAs in their project selection process. Tribes such as the Tohono O’odham Nation have worked with State and local agencies to conduct RSAs and implement RSA findings. However, while RSAs have secured a foothold with FLMAs and Tribes, more opportunities exist to promote RSAs as a tool to address safety on and adjacent to Federal and Tribal lands. Some examples include introducing FLMAs and Tribes to the RSA process, initiating full-fledged programs within agencies, and incorporating RSAs into the planning process, thus promoting a more comprehensive approach to addressing safety.

RSAs on Federal or Tribal facilities may encounter unique geometric and roadside conditions with significant historical, cultural, and environmental constraints.

Conducting an RSA does not require a large investment of time or money. RSAs require only a small percentage of the time and money needed for a typical roadway project. Furthermore, by gaining a better understanding of the safety implications of roadway and roadside features, RSAs can be used to prioritize locations with safety issues which help identify the best use for funding. Other benefits include encouraging multidisciplinary collaboration beyond the RSA, which promotes a better understanding of road user needs and safety.

RSAs will help save lives and reduce injuries. The success of RSAs has led to FHWA adopting the process as one of its nine “proven safety countermeasures.” The success has been realized by many FLMAs and Tribes, which are planning and/or conducting a number of RSAs with various partners.

Perhaps the best way to describe the effectiveness of RSAs is through a benefit/cost (B/C) ratio. A benefit/cost ratio is a measure to compare the benefits derived from the reduction of crashes to the cost of conducting an RSA and implementing crash reduction strategies. Benefit/cost ratios may be used as the ultimate measure of the project’s success. The following case studies show the potential benefits of conducting RSAs.

RSA Success Stories

|

Roadway

|

Intersection

|

This Toolkit is intended to be used by Federal land agencies and Tribal governments as guidance and to provide information, ideas, and resources in key topic areas to lead the effort to improve safety through the use of the RSA:

The Toolkit serves as a starting point, providing information to FLMAs and Tribes about identifying an RSA champion, partnerships needed to build support, available funding sources (for both the program and improvements), tools to conduct RSAs, and resources to identify safety issues and select countermeasures. Worksheets and other sample materials have been provided to aid in the RSA process, including requesting assistance, scheduling, analyzing data, conducting field reviews, and documenting issues and suggestions. Examples of programs and experiences of other agencies have also been included throughout to provide examples of successes and struggles in implementing RSAs and improving safety for all road users.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| “4 E’s” | Engineering, Education, Enforcement, and Emergency Medical Services |

| ADOT | Arizona Department of Transportation |

| B/C | Benefit/Cost |

| BIA | Bureau of Indian Affairs |

| BLM | Bureau of Land Management |

| CCP | Comprehensive Conservation Plan |

| CFLHD | Central Federal Lands Highway Division |

| COG | Council of Governments |

| DOI | United States Department of the Interior |

| DOT | Department of Transportation |

| EFLHD | Eastern Federal Lands Highway Division |

| EMS | Emergency Medical Services |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration |

| FLH | Federal Lands Highway |

| FLMA | Federal Land Management Agency |

| FS | United States Forest Service |

| FTA | Federal Transit Administration |

| FWS | United States Fish and Wildlife Service |

| GMP | General Management Plan |

| HSIP | Highway Safety Improvement Program |

| IHS | Indian Health Service |

| IRR | Indian Reservation Roads Program |

| ITCA | Inter Tribal Council of Arizona |

| LTAP | Local Technical Assistance Program |

| MPO | Metropolitan Planning Organization |

| NCHRP | National Cooperative Highway Research Program |

| NEPA | National Environmental Protection Agency |

| NPS | National Park Service |

| NRDOT | Navajo Region Division of Transportation |

| PLHD | Public Land Highway Discretionary Program |

| RFP | Request for Proposal |

| RPC | Regional Planning Commission |

| RSA | Road Safety Audit/Assessment |

| SRTS | Safe Routes to School Program |

| STIP | Statewide Transportation Improvement Program |

| STP | Surface Transportation Program |

| TE | Transportation Enhancement |

| THSIP | Tribal Highway Safety Improvement Project |

| TIP | Transportation Improvement Program |

| TTAP | Tribal Technical Assistance Program |

| TTIP | Tribal Transportation Improvement Program |

| UDOT | Utah Department of Transportation |

| WFLHD | Western Federal Lands Highway Division |

| WisDOT | Wisconsin Department of Transportation |

This chapter provides critical information needed to conduct an RSA. Special considerations for FLMAs and Tribal transportation agencies in each step of the 8-step RSA process are described to help improve safety on and adjacent to Federal and Tribal lands.

A Road Safety Audit/Assessment (RSA) is a formal safety performance examination of a future roadway project or an in-service facility that is conducted by an independent, experienced, multidisciplinary RSA team.

The primary focus of an RSA is safety while working within the context of the facility’s existing mobility, access, surrounding land use, and/or aesthetics. RSAs enhance safety by considering potential safety issues presented to all road users under all conditions (e.g., day/night and dry/wet conditions). By focusing on safety, RSAs ensure that potentially hazardous roadway and roadside elements do not “fall through the cracks.”

RSAs are commonly confused with other review processes, particularly traditional safety reviews. Traditional safety reviews are missing one or more of the key elements of an RSA. Table 1 compares the key elements of an RSA with the elements that are typically part of a traditional safety review or other safety study.

Table 1: What are RSAs?

| RSAs are: | RSAs are not: |

|---|---|

|

|

The RSA process may be employed on any type of facility and during any stage of the project development process, including existing facilities that are open to traffic. RSAs conducted during the pre-construction phase can be particularly effective because there is an opportunity to address a number of safety issues. RSAs conducted in later stages have less ability to address these issues.

In addition to vehicular traffic safety issues, RSAs can also be oriented to specific user groups such as pedestrians and bicyclists. The RSA would still consider all potential users but may have a particular consideration for the needs of a specific group.

Common factors leading to requests for RSAs during the existing road stage include high crash frequencies, high profile crash types or political influence, and significant changes in traffic characteristics (current or expected). A potential factor leading to the request for an RSA in the planning or construction phase includes novel designs for the area, such as the introduction of a roundabout. Another factor may be a major change in the surrounding land use that accompanies the project.

The selected project should be scoped in size so that the RSA can be accomplished in a reasonable amount of time, usually two to three days or one week at most. For a corridor, this is generally a corridor of one to two miles in length or a longer corridor that is concentrated on issues at four or five spots within the corridor. For intersection projects, the scope should be limited to a series of four or five intersections.

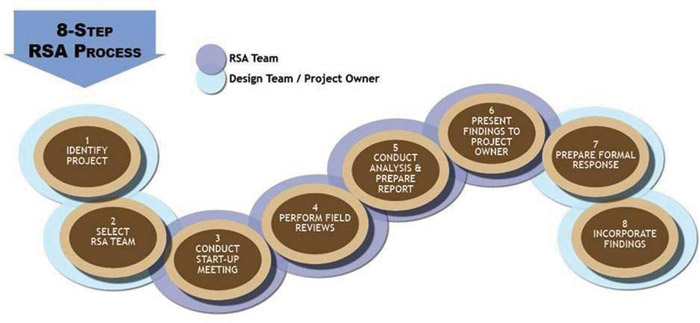

The FHWA Road Safety Audit Guidelines document (Publication FHWA-SA-06-06) describes the 8-step process for conducting RSAs. These steps are shown in Figure 1 illustrating the primary responsibilities of the project owner/design team and the RSA team. This section describes how these steps apply to an RSA conducted on or near Federal or Tribal lands.

Figure 1 : RSA Process

STEP 1: Identify Project or Existing Road for RSA

STEP 1: Identify Project or Existing Road for RSATypically, the facility or project owner identifies the location(s) to be reviewed during the RSA. Jurisdictional authority of facilities involving Federal or Tribal lands can be unique. It is common that RSAs conducted at the request of FLMAs or Tribal transportation agencies are on facilities with different ownership, such as a State or local agency. In this case, a facility or project identified by a FLMA or tribe would need to contact the owning agency to request an RSA. For instance, a request may be initiated because of safety concerns about a road running adjacent to or through a Federal or Tribal land.

If, however, the FLMA or Tribal government is the owner, the approach can be decided internally within the agency. Depending on factors such as available staffing and funding, one of the following approaches may be taken:

Once the facility or project is identified, the RSA scope, schedule, team requirements, tasks to be completed, report format and content, and response procedures should be defined.

The appropriate season for the RSA review should also be established. For example, special events, or seasonal conditions are important to consider for the timing of the RSA.

STEP 2: Select Independent and Multidisciplinary RSA Team

STEP 2: Select Independent and Multidisciplinary RSA TeamSelecting a knowledgeable RSA team is vital to the success of an RSA. The facility or project owner is responsible for selecting the RSA team or the RSA team leader. Regardless of ownership the assistance of other local agencies may be sought due to their familiarity with the area. It is important that the RSA team is independent of the operations of the road or the design of the project being assessed to assure two things: that there is no bias in the assessment and the project is reviewed with “fresh eyes.”

See the Resource Materials section for items to assist with identifying an approach to conduct an RSA:

The RSA team should include (but are not limited to) individuals with the following expertise:

Depending on different needs, the RSA team could include other specialists to ensure that all aspects of safety performance of the given facility can be adequately assessed.

The size of the RSA team may vary. The best practice is to have the smallest team that brings all the necessary knowledge and experience to the process for the specific location(s) being reviewed. As a general rule, the RSA team should be able to travel in one vehicle (except for police and EMS) so the team can review and discuss conditions in the field collectively.

Case Study

An RSA for the Navajo Nation in San Juan County, Utah included team members from the Navajo DOT, Navajo police, Utah DOT (UDOT), Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), Indian Health Services (IHS), FHWA, and the County. All members provided useful insights during the RSA process and several team members commented on the benefit of listening to and learning from their teammates who provided a different perspective on the safety issues and potential improvements. In particular, the public health representative contributed valuable information regarding road-user demographics as well as opportunities for educational improvements, such as road safety campaigns.

STEP 3: Conduct Start-up Meeting to Exchange Information

STEP 3: Conduct Start-up Meeting to Exchange InformationThe purpose of the start-up meeting is to ensure the project owner/design team and all RSA team members understand the purpose, schedule, and roles and responsibilities of all participants in the RSA. This meeting helps establish lines of communication between the RSA team leader and the project owner/design team. At the end of the meeting, all parties should have a clear understanding of the scope of the RSA to be undertaken and each of their roles and responsibilities. Specific topics of discussion may include:

If possible, the owner and/or design team should provide data describing the existing and planned conditions (if applicable) as well as the existing safety performance (e.g., crash records/data, traffic volumes, etc.). Ideally data will be provided prior to the start-up meeting for review/analysis by the RSA team. This will enable the team to ask detailed questions at the start-up meeting. Naturally the desired data may not be readily available; however, any information that can be provided to the RSA team is beneficial to the understanding of the location(s) to be reviewed and the potential safety issues.

See the Resource Materials section for items to assist with the start-up meeting:

STEP 4: Perform Field Reviews under Various Conditions

STEP 4: Perform Field Reviews under Various ConditionsThe RSA team should review the entire site (as well as plans if conducting an RSA of a design), documenting potential safety issues and project constraints (e.g. available right-of-way, impact on adjacent land). Issues identified in the review of project data (e.g., safety concerns related to crash clusters) should be verified in the field. Key elements to observe include:

The FHWA Road Safety Audit Guidelines and Pedestrian Road Safety Audit Guidelines and Prompt Lists provide prompts to help the RSA team identify potential safety issues and ensure that roadway elements are not overlooked.

A thorough site visit will include field reviews under various conditions. At a minimum, the RSA team should review the site during the following conditions:

See the Resource Materials section for items to assist with the field review:

STEP 5: Conduct RSA Analysis and Prepare Report Findings

STEP 5: Conduct RSA Analysis and Prepare Report FindingsThe RSA team conducts an analysis to identify safety issues based on data from the field visit and preliminary documents. The safety issues may be prioritized by the RSA team based on the perceived risk. For each identified safety issue, the RSA team generates a list of possible measures to mitigate the crash potential and/or severity of a potential crash. Chapter 2 provides more detailed information on this step of the process.

The RSA team then prepares a summary of the safety issues and related suggestions for improvement. Prior to preparing a report, the team may meet with the owner and/or design team to discuss preliminary findings (Step 6).

The RSA report should include a brief description of the project, a listing of the RSA team members and their qualifications, a listing of the data and information used in conducting the RSA, and a summary of findings and proposed safety measures. It should include pictures and diagrams that may be useful to further illustrate issues and countermeasures.

See the Resource Materials section for additional guidance on report content and format:

STEP 6: Present RSA Findings to Owner/Design Team

STEP 6: Present RSA Findings to Owner/Design TeamThe results of the RSA are presented to the owner/design team. The purpose of this meeting is to establish a basis for writing the RSA report and to ensure that the report will adequately address issues that are within the scope of the RSA process. This is another opportunity for discussion and clarification. The project owner/design team may ask questions to seek clarification on the RSA findings or suggest additional/alternative mitigation measures.

STEP 7: Prepare Formal Response

STEP 7: Prepare Formal ResponseOnce the owner and/or design team have reviewed the RSA report, they should prepare a written response to its findings. The response should outline what actions the owner and/or design team will take with respect to each safety concern listed in the RSA report. A letter, signed by the project owner, is a valid method of responding to the RSA report. The RSA findings may be presented in a public meeting or the report could be made available to the public to help garner support for the findings and the overall RSA process. This can be particularly beneficial on projects with a high degree of public involvement, such as pedestrian facilities.

STEP 8: Incorporate Findings into the Project when Appropriate

STEP 8: Incorporate Findings into the Project when AppropriateAfter the response to the RSA report is prepared, the project owner and/or design team should work to implement the agreed-upon safety measures or create an implementation plan. RSA findings can be incorporated into an agency’s planning process, as discussed in Chapter 4. An important consideration is to evaluate the RSA program and share lessons learned. An RSA “after action review” can be scheduled for the RSA team to evaluate the effectiveness of the suggested measures implemented and to evaluate if other measures are needed.

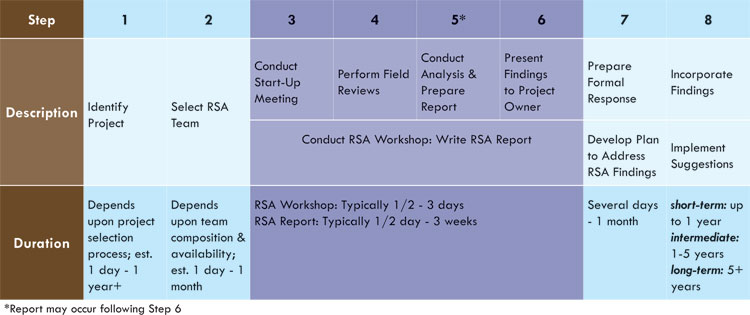

The time and cost to complete an RSA vary based upon conditions such as project extents, level of detail, logistics, and team size. Figure 2 presents a generalized timeline of the RSA process. Please note that the writing of the report does not necessarily have to occur in Step 5; it can be completed following the presentation of preliminary findings in Step 6.

Figure 2: RSA Time Requirements by Step

In total, the entire RSA process (Steps 1 through 8) could range from a month to a couple years. The cost to conduct an RSA depends largely upon the approach (discussed in Step 1) and the level of effort required by the RSA team.

Several Federal, Tribal, State, and local agencies have used RSAs as a tool for improving safety. Initially, it is important to identify a local champion, either internally or externally, to support the RSA and its outcome (see Chapter 3 for more details). If the RSA is on or adjacent to Federal or Tribal lands, the local champion should be able to communicate effectively with all parties involved. It is particularly important to communicate the need for and desired outcome of an RSA. The next challenge is to assemble an independent RSA team. Since independence is a requirement of an RSA, the agencies may contact the State and/or local DOT, Local and/or Tribal Technical Assistance Program (LTAP/TTAP) center, FHWA Division Office, FHWA’s RSA Peer-to-Peer Program, FHWA’s Federal Lands Division Office, or FHWA’s Offices of Safety and Federal Lands Highway for assistance in finding team members. Federal and Tribal transportation agencies may also find it helpful to contact staff from other nearby Federal agencies or Tribes with whom they may establish a reciprocal relationship.

RSAs conducted on or near Federal or Tribal lands may necessitate involvement from multiple agencies.

This chapter describes potential safety issues identified on Federal and Tribal lands as well as a list of potential low-cost countermeasures for addressing these issues. A basic prioritization methodology is also discussed.

Most issues on or adjacent to Federal and Tribal lands have both an engineering and behavioral element. For example, traffic types and volumes may be inconsistent with the intended roadway design due to changes in the functionality of the roadway and land use in surrounding areas. This may result in a roadway serving mostly commuter traffic, an increase in heavy vehicular traffic, or seasonal traffic peaks and variations. As such, shoulder widths and roadsides may not adequately address the increased risk to drivers. From a behavioral standpoint, lack of awareness of the intended purpose of the roadway may result in motorists not applying the appropriate driving techniques for the conditions. Furthermore, driver expectancy of other road users such as pedestrians and bicyclists may not reflect the intended usage.

The RSA team should determine the safety issues while considering the infrastructure and the behavior elements. Table 2 illustrates common safety issues and behavioral aspects relating to these issues on or near Federal and Tribal lands listed by roadway element. The RSA team is charged with determining specific roadway and behavioral issues for the specific project they are assessing. The documents in the Resource Materials section provide further detail with regard to the issues presented here and to other potential safety hazards that an RSA team should be aware of when conducting a field review.

Table 2 also presents common countermeasures that may be used to address road safety issues on or near Federal and Tribal lands. This list is not comprehensive; it is intended to provide general guidance to typical countermeasures. Note that the countermeasures identified in this list are primarily low-cost engineering measures, although a few relatively high-cost options are included because they are considered to be “proven” countermeasures. A few specific education and enforcement measures are identified as well, but a more general discussion of how to incorporate education, enforcement, and EMS countermeasures is provided in the following section. The documents in the Resource Materials section provide a much wider and detailed range of potential countermeasures and their effectiveness and should be used as guidance when considering safety measures during the RSA process.

Table 2: Common Safety Issues and Countermeasures

| Topic Area | General Issues |

Example Observations |

Example Countermeasures |

|---|---|---|---|

Cross-section |

Limited pavement width |

Narrow or no paved shoulders |

Improve/stabilize unpaved shoulders Install safety edge Install new paved shoulders or widen existing paved shoulders Install centerline or edgeline rumble strips or rumble stripes |

Pavement edge drops |

Vertical pavement edge drops greater than two inches |

||

Horizontal curves |

Sharp curves |

Limited sight distance |

Install advance curve warning (with/without advisory speed) Install centerline and edgeline pavement markings Improve delineation (e.g., chevrons, post-mounted delineators) Upgrade existing signs (size, retroreflectivity, location) Improve skid resistance with high-friction treatment (e.g., NovaChip, microsurfacing, etc.) |

Inadequate superelevation |

|||

Various levels of delineation |

Inconsistent and old signing |

||

Faded pavement markings; no edgelines |

|||

Roadside hazards |

Common roadside hazards located in close proximity to the roadway |

Trees, rocks, utility poles, guide wires |

The order of preference for treating roadside hazards (from most preferred to least preferred) (1) is to:

(1) American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Roadside Design Guide. 2002 3rd Edition with 2006 Chapter 6 Update. |

Steep embankments |

|||

Drainage features (inlets, headwalls, culverts) |

|||

Large bodies of water |

|||

Intersections |

Lack of driver expectancy |

Sight distance to the intersection |

Enhance driver expectation of intersections (e.g., advance pavement markings and/or signs, lateral rumble strips) Provide adequate sight distance to intersection Enhance conspicuity of signs and pavement markings (size, retroreflectivity, location, number) Improve line of sight at the intersection/provide clear sight triangles Reduce conflict points by installing turn lanes and consolidating driveways (access management) Provide lighting Consider roundabouts |

Obstructions in the sight triangle |

Sight distance at the intersection |

||

Driver behavior |

Poor gap acceptance at stop-controlled intersections |

||

Lighting |

Roadway and intersection lighting |

Inadequate or lack of lighting |

Install/improve lighting along roadway or at intersections |

Pedestrians and bicyclists |

Lack of designated facilities for pedestrians and bicyclists |

No sidewalks or shared use paths and limited shoulders |

Provide designated pedestrian and bicycle facilities Install or widen paved shoulder to a minimum of four feet for use by pedestrians and bicyclists Construct a shared use path Enhance driver awareness of pedestrians, bicyclists, and crossings (e.g., warning signs, pavement markings, standard and/or hybrid signals) Provide median refuge areas Provide educational information to road users with regard to safe use Enforce pedestrian and bicycle laws |

Driver behavior |

Lack of driver awareness of pedestrians and bicyclists |

||

Pedestrian and bicyclist behavior |

Lack of familiarity with road network and safety issues (tourists) |

||

Animals |

Open range livestock |

Roadside grazing |

Enhance driver awareness of animals and animal crossings (e.g., signs) Install animal/wildlife fencing to reduce the number of potential conflict points Construct wildlife crossings (i.e., overpasses and underpasses) along primary migratory/feeding routes Enact and enforce laws to prohibit grazing within the right-of-way Educate owners about animal control laws and liability |

Wildlife |

Annual migration routes |

||

Speed management |

High vehicle speeds |

Limited enforcement due to large jurisdictions |

Coordinate with local enforcement to conduct targeted speed enforcement Consider alternative measures (e.g., speed trailers) Install gateway treatments at the entrances to towns |

Vehicle mix |

All Terrain Vehicles (ATVs)/Snowmobiles Trucks and buses |

ATVs or snowmobiles on and along the roadway |

Provide educational information to road users with regard to safe operating/use Install warning signs and markings to indicate ATV/snowmobile crossings Inform ATV/snowmobile riders of appropriate/designated trails Coordinate with local enforcement Support educational campaigns by enforcing ATV/snowmobile operations Provide sidewalks or shared-use paths to separate non-motorized road users |

Access to facilities and communities |

Location |

Limited sight distance/awareness of facilities |

Enhance driver awareness of facilities/communities (e.g., advance warning signs and/or guide signs, gateway treatments) Clear sight triangles at entrances/exits Separate turning vehicles by installing left- and/or right-turn lanes Install shared use path or provide an adequate shoulder to separate pedestrians and bicyclists from motor vehicle traffic Conduct a parking study Identify current occupancy and determine needed capacity Identify opportunities to provide better connectivity between parking facilities and pedestrian/bicycle generators |

Parking |

Limited capacity (spillover) Lack of connectivity to destinations |

Safety issues cannot be completely addressed through engineering alone. The other “E’s” include education, enforcement, and emergency medical services (EMS). The RSA team should encourage and suggest measures that consider all “4 E’s” to address specific safety issues. Communication and coordination among the “E’s” is essential to ensuring safety is addressed at a comprehensive level. The agencies conducting RSAs may need to regularly assemble representatives from each of the “4 E’s” to ensure that countermeasures and strategies are complementing one another. Some examples of education, enforcement, and EMS countermeasures are presented below; NCHRP Report 622 provides a more complete description of countermeasures that may aid education, enforcement, and EMS safety strategies (see Resource Materials section for complete reference). Although the report is based on countermeasures targeting a State Highway Safety Office audience, the information provided may be applicable to safety issues observed by Federal and Tribal agencies.

Education – All road users must be aware of the safe and proper way to use roads. Due to the unique characteristics of Federal and Tribal land roadways, users need to be made aware of safe travel practices and potential hazards. Example methods of transferring this information include postings on the internet, brochures provided at visitor’s centers, and video messages. Additional information on effective education strategies may be acquired through outreach groups such as Tribal Technical Assistance Programs (TTAPs).

Enforcement – Laws are intended to control the operation of road users. Enforcing speed limit and compliance with signal/sign indications, as well as correcting wrong-way riding and impaired driving create a safer travel environment for all road users. Staffing and funding constraints may limit the ability of a Federal or Tribal land agency to provide comprehensive enforcement; however, efforts should be made to target specific issues or frequent or high-risk behaviors. This can be done by identifying prevalent factors that contribute to crashes along the roadway of interest and targeting behaviors that relate to those issues. For example, if alcohol was determined to be a primary contributing factor in 50 percent of fatal and injury crashes along a specific route, it may be appropriate to deploy a checkpoint to combat drinking and driving; this could be further targeted by identifying the time of day and day of week when this behavior is most likely to occur.

Law enforcement on RSAs is helpful to identify safety issues as well as to suggest targeted enforcement countermeasures.

Emergency Medical Services – The rural nature of many roadways on or near Federal or Tribal lands may play a major role in limiting the ability to provide timely medical treatment to people injured in a crash. Factors contributing to response time include the ability of other motorists to identify a crash and to notify emergency personnel, the ability of emergency personnel to quickly respond to the scene, and the ability to quickly transport the victim(s) to a trauma center. Adequate cell phone service coverage and routine patrols are a few methods that can help save a life in the event of a serious injury.

A prioritization process is useful for identifying the most pressing safety needs based on the findings of the RSA team. Table 3 is a matrix that can be used in the prioritization process. In general, issues associated with more frequent crashes and higher severity levels tend to be given higher priority. The prioritization can be based on historical crash data, expert judgment (provided by the RSA team), or a combination of the two.

Table 3: Issue Prioritization Matrix

| Frequency of Crashes | Severity of Crashes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Possible/Minor Injury |

Moderate Injury |

Serious Injury |

Fatal |

|

Frequent |

Middle-High |

High |

Highest |

Highest |

Occasional |

Middle |

Middle-High |

High |

Highest |

Infrequent |

Low |

Moderate |

Middle-High |

High |

Rare |

Lowest |

Low |

Middle |

Middle-High |

For many RSAs conducted in rural areas, reliable crash data are not available. Anecdotal information (e.g., from maintenance, enforcement call logs, land owners) and evidence of conflicts and crashes (e.g., skid marks and fence strikes) help to create a more complete picture of potential hazards, but cannot be quantified with any certainty. In these cases, the likely frequency and severity of crashes associated with each safety issue are qualitatively estimated, based on the experience and expectations of RSA team members. Expected crash frequency can be qualitatively estimated on the basis of exposure (how many road users would likely be exposed to the identified safety issue?) and probability (how likely was it that a collision would result from the identified issue?). Expected crash severity can be qualitatively estimated on the basis of factors such as anticipated speeds, expected collision types, and the likelihood that vulnerable road users would be exposed. These two risk elements (frequency and severity) are then combined to obtain a qualitative risk assessment.

This section describes the process to initiate an RSA program, including potential program structures, partners, and funding sources. Discussion on how to prioritize locations to conduct RSAs is also included. It presents potential challenges and provides suggestions for overcoming these challenges. Finally, it suggests performance measures that may be used to evaluate the progress and success of the program.

The successful integration of RSAs into any agency requires several important elements: management commitment, an agreed-upon policy/process, informed project managers, an ongoing training program, and skilled RSA team members. Program structures vary by agency depending on the goals and objectives as well as available resources and level of training. The FHWA Road Safety Audit Guidelines recommends an approach for introducing RSAs that typically includes:

There are numerous methods for prioritizing RSA locations. The method of choice will depend on the availability of staff and data resources, as well as the number of requests for RSAs. If RSA efforts are request-based, it is not necessary to waste valuable resources on a complex prioritization process when the number of requests is relatively low; it may suffice to simply prioritize locations on a first-come-first-served basis. As the number of requests increases, it will become necessary to prioritize and perhaps even screen locations, which requires a formal (and likely data-driven) process. This does not mean that the process has to be completely quantitative and objective. However, good transportation safety planning should focus RSA efforts on areas with the highest concentration of crashes, particularly deaths and injuries. Other factors to be considered can include timeframe, cost, relation to overall program goals, and stakeholder support. Chapter 2 of the FHWA Road Safety Audit Guidelines suggests an application of nominal (compliance to design standards) and substantive (crash performance) safety concepts to prioritize locations; please refer to that publication for more information.

An RSA program may be established by and housed at any one of a number of agencies. Regardless of where the program is housed, it is critical to identify a champion to lead and promote the RSA program (or at least the establishment of the RSA program) at the highest level of the organization. Depending on factors such as available staff, experience, and funding, FLMAs or Tribes may decide to identify a champion internally within their own agency or seek an external champion. A champion may be an individual or may be an entire agency or department of an agency. In any event, the champion should be knowledgeable of the RSA process and potential benefits so that RSAs can be introduced to others to promote awareness and foster support.

While the champion is responsible for introducing and promoting RSAs, there is a need to identify a support network to provide staff, funding, expertise, and public and political support. Table 4 identifies potential partners that could help establish, house, staff, fund, or support an RSA program.

Table 4: RSA Program Participation

| Potential Partners for RSA Program | House |

Staff |

Fund |

Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tribal/State/Local DOT |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Forest Service |

|

X |

X |

X |

National Park Service |

|

X |

X |

X |

Fish and Wildlife Service |

|

X |

X |

X |

Tribal Technical Assistance Program |

X |

X |

X |

X |

FHWA (including Federal Lands and Federal Aid Division offices) |

|

X |

X |

X |

BIA Division of Transportation |

|

X |

X |

X |

Public health agencies/officials |

|

X |

X |

X |

Public officials |

|

|

X |

X |

Other groups (e.g., community safety teams) |

|

X |

|

X |

Tribal Cultural Officials |

|

X |

|

X |

An important consideration when establishing an RSA program is funding, not only for the functionality of the program but also for the implementation of proposed safety improvements. A number of funding resources are provided in this section for initial guidance. In addition to these resources, it is recommended that Federal and Tribal agencies consult their local FHWA division, State DOT, and local Metropolitan Planning Organization/Council of Governments/Regional Planning Commission (MPO/COG/RPC) offices to learn more about available funding mechanisms. Up-to-date information on funding opportunities can also be obtained by visiting the following websites:

The Federal government provides funding assistance for eligible activities through legislative formulas and discretionary authority, including some 100 percent Federal-aid programs and programs based on 90/10 or 80/20 Federal/local matches. The Tribal Highway Safety Improvement Implementation Guide advises that the implementation plan for a Tribal Highway Safety Improvement Project (THSIP) or highway safety project will depend greatly on which funding sources the Tribes pursue, since each source has different program eligibility requirements. Some of the important safety-funding sources are presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Potential Funding Sources

| Source | Website |

Purpose / Use |

|---|---|---|

Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) |

Projects that improve safety. |

|

Surface Transportation Program (STP) |

Projects on Federal-aid highways, including the NHS, bridge projects on any public road, transit capital projects, and intracity/intercity bus facilities. Now limited to urban areas. |

|

Transportation Enhancement (TE) |

Projects involving pedestrian facilities and scenic highways. |

|

Safe Routes to School (SRTS) Program |

Enable and encourage children to walk and bike to school. |

|

National Scenic Byway Program |

Nationally or locally designated roads with outstanding scenic, historic, cultural, natural, recreational, and archaeological qualities. |

|

Indian Reservation Roads (IRR) Program |

Planning, design, construction, and maintenance activities addressing Tribal transportation needs. |

|

Park Roads and Parkways Program |

Design, construction, reconstruction, maintenance, or improvement of roads and bridges providing access to or within a unit of the National Park Service. |

|

Refuge Roads Program |

Design, construction, reconstruction, maintenance, or improvement of roads and bridges providing access to or within a unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System. |

|

Forest Highway Program |

Resurface, restore, rehabilitate, or reconstruct roads providing access to or within a unit of the National Forest or Grassland. |

|

Public Lands Highway Discretionary (PLHD) Program |

Planning, research, engineering, and construction of highways, roads, parkways, and transit facilities within, adjacent to, or providing access to reservations and Federal public lands. |

|

Indian Health Service Injury Prevention Program |

Basic and advanced injury prevention projects. |

Wilson and Lipinski (Eugene Wilson and Martin Lipinski. NCHRP Synthesis 336: Road Safety Audits, A Synthesis of Highway Practice (National Cooperative Highway Research Program, TRB, 2004)) noted in their synthesis of RSA practices in the United States that the introduction of RSAs or an RSA program can face opposition based on liability concerns, the anticipated costs of the RSA or of implementing suggested changes, and commitment of staff resources. Other challenges include cultural and institutional barriers (e.g., lack of support from within), lack of RSA training, and lack of long-term support.

The following were identified as potential challenges to establishing an RSA program; methods to overcome each potential challenge are also presented. Note that education and awareness are a common theme.

As support is gained to establish an RSA program, it will be useful to begin to define goals and performance measures. Goals help to guide the direction of the program while performance measures help to identify the success of the program. Performance measures are also important because they can be used (or may be required) to obtain or renew funding. Example goals and performance measures are presented in Table 6.

Table 6: Example Goals and Performance Measures

| Goal | Performance Measure |

|---|---|

Provide RSA training to X percent of agency personnel with Y years. |

Percentage of personnel trained to conduct RSAs. |

Conduct X RSAs per year at high-crash/risk and/or high-profile locations. |

Number of RSAs conducted per year. |

Reduce injuries and fatalities by X percent per year with low-cost, quickly implemented improvements. |

Number of total crashes or specific crash types/severities at locations where RSAs are conducted. |

This section describes the process for integrating RSAs in the planning process, including potential partners, implementing RSA findings, and potential challenges.

Many of the same partners identified to assemble an RSA team are the same partners that can assist in integrating an RSA program into the planning process. For example, the Office of Federal Lands Highway provides “program stewardship and transportation engineering services for planning, design, construction, and rehabilitation of the highways and bridges that provide access to and through Federally-owned lands.” FLH consists of the following: Eastern, Central, and Western Federal Lands Highway Divisions as well as the Headquarters office. These units of the FLH work with Tribes, FLMAs, and States to address and improve safety. FHWA’s Division Office in each state is also a resourceful partnering agency.

RSAs on Federal and Tribal Lands often require unique partnerships to assess safety. These partnerships can be critical in incorporating long-term suggestions or establishing a long-term RSA program.

State DOTs, MPOs, and COGs are also open to forming partnerships with Federal and Tribal land agencies. Several DOTs have internal departments devoted specifically to setting up partnerships between agencies. Federal and Tribal land agencies also have formed committees and councils to communicate their needs to DOTs, MPOs, and COGs. By working together, agencies have realized the benefits of cooperative participation where the needs and concerns of all parties involved can be voiced and addressed in a timely and efficient manner.

Case Study

In Arizona, coordination and information sharing between the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) and the Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, Inc. (ITCA) have advanced consultation activities between ADOT and tribal governments in transportation planning efforts. The partnering between ADOT and the ITCA has (1) provided insight to ADOT staff of the challenges facing tribes throughout the state, and (2) increased awareness amongst tribal transportation staff of the opportunities for input into state-level transportation planning efforts. Besides the ITCA, ADOT has formed partnerships with other agencies: Arizona State Land Department, Arizona Tribal Strategic Partnering Team, Bureau of Land Management, the United States Forest Service, and FHWA. These partnerships have helped effectively streamline tribal transportation consultation in Arizona. In an effort to assist tribal governments and tribal planning departments in understanding the ADOT transportation planning and programming processes, ADOT has developed Transportation Planning and Programming – Guidebook for Tribal Governments.

The Arizona Tribal Transportation website (http://www.aztribaltransportation.org/) provides a wealth of information with regard to state-tribal transportation related partnerships, projects, activities, and funding resources. Other helpful information can be found on ADOT’s partnering office website and on the ITCA website.

Case Study

The Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) has formed a formal partnership with the State’s Federally-recognized Tribes. The Wisconsin State Tribal Relations Initiative recognizes the government-to-government relationship between the State and Tribal governments. As such, the State-Tribal Consultation Initiative is poised at improving communication between State and Tribal representatives to ensure that concerns and issues are addressed in a timely and efficient manner. This partnership is applied through the WisDOT Tribal Task Force. Since 2008, the task force has provided funding for the Tribes to conduct RSAs. Many of the RSAs were targeted at Reservations where WisDOT was planning roadway improvements.

Step 8 of the RSA process introduced in Chapter 1 involves the implementation of safety improvement measures identified by the RSA team. Incorporating RSA findings into the planning process is largely dependent on the desired timeframe for implementation (i.e., short-, intermediate-, or long-term). Short-term improvements (e.g., signing, pavement markings, and vegetation control) can often be handled through maintenance activities. Intermediate- and long-term improvements (e.g., updating/installing guardrail, installing a shared use path, realigning/widening, etc.) can be integrated into local, regional, and State transportation improvement programs and plans. It is important for all parties involved in the RSA process to understand the intent and extent of these programs as they pertain to the area being studied so that safety issues may be addressed in an appropriate timeframe.

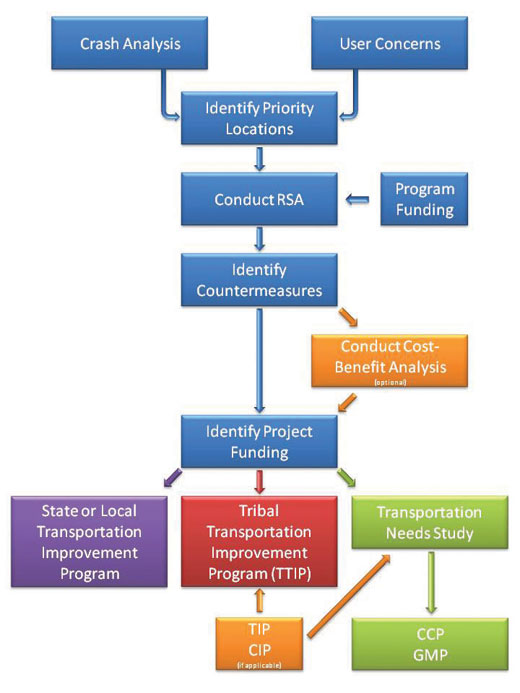

Transportation agencies are charged with developing long-range plans for the transportation systems on State, Tribal, and Federal lands. Examples include the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), Tribal Transportation Improvement Program (TTIP), Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP), and General Management Plan (GMP). A major component of these plans is a comprehensive transportation study which identifies short- and long-term needs. The findings on an RSA are important to fully addressing these needs.

A brief description of the identified programs and plans is provided. For specific information regarding the long-range plans in your area, contact your State DOT, Tribal DOT, or FLH. Figure 3 illustrates how RSAs contribute to the overall planning process.

Figure 4 : RSAs in the Planning Process

Much like the challenges faced when establishing an RSA program, similar challenges may be realized when incorporating an RSA program into the planning process. Identifying appropriate partners and obtaining funding is described in Chapter 3. Other challenges include the availability of data and jurisdictional boundaries.

Data Quantity and Quality – For many RSAs conducted on Federal and Tribal lands, the lack of data and/or the poor quality of available data are issues when identifying and prioritizing locations. In many instances, crashes are not formally documented. When documents have been prepared, the data may be incomplete or inaccurate. These data constraints do not help pinpoint locations in need of attention or provide a good understanding of the safety hazards, thus making it difficult to program appropriate measures into transportation improvement plans.

Case Study

An RSA conducted on the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge study area revealed that many run-off-the- road crashes were not reported as a result of the location of the crash. Vehicles involved in run-off-the-road crashes along a State roadway going through the refuge were not represented in the crash reports; once the vehicle leaves the roadway it enters Federal refuge property. The motorist is responsible for removing the vehicle and it is not reported by the police.

The lack of data and/or the poor quality of available data can be overcome by using alternative methods for identifying and prioritizing locations for RSAs. Consulting with local law enforcement, emergency medical services, health services, and/or the public can help with the identification of common issues and problematic locations that could be considered as potential candidates for an RSA. Law enforcement and public input provides anecdotal information that often helps create a more complete picture of potential hazards even without quantifiable data. The inputs to the process can be a combination of objective and subject measures depending on the availability, quality, and detail of the data (see Chapter 2).

Jurisdictional Boundaries – Ownership of facilities or projects involving Federal or Tribal lands can be unique. For example, an RSA may be conducted on a state-owned roadway that travels through or adjacent to a Federal land. In other cases, local agencies such as counties, townships, and villages may also have roadway jurisdiction. When a facility or project is under multiple jurisdictions, there are multiple interests that are involved. One challenge is to ensure that all parties affected by programs or initiatives are well informed and that concerns are received and addressed appropriately. Another challenge is to determine which jurisdiction is responsible for planning and implementing changes, performing maintenance activities, providing enforcement, and keeping up-to-date records. This can become particularly difficult when multiple agencies are involved, especially when staffing and financial responsibility must be assigned. It is important to realize, though, that while the ownership of a facility or project can be very complex and present difficult challenges, there are also benefits of multi-agency involvement. For example, funding for reconstruction and maintenance may be limited for an individual agency, but options can be identified for pooling resources to implement suggested RSA improvements.

Case Study

An RSA for the Navajo Nation was conducted along N-35. The portion of the N-35 corridor studied is a Federal Aid Highway. A portion of the roadway (milepost 0 to 18) is owned by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Phillips Oil Company paved a section of N-35 (milepost 18 to 23), but road ownership remains with the Navajo Nation. Funding for reconstruction and maintenance of N-35 comes from several sources, including the Indian Reservation Roads Program, Congressional earmarks, and the BIA road maintenance program. The funding for road improvements is administered by the Navajo Region Division of Transportation (NRDOT) through the IRR Program within the Federal Lands Highway Program. Funding for road maintenance comes from the Department of the Interior (DOI) and is also administered by the NRDOT. They have contracted San Juan County to maintain much of the roads in the county, including N-35. San Juan County is responsible for signing, pavement markings, and roadside mowing.

Effective communication between all parties in the RSA process is important to overcome jurisdictional boundaries. It is also important to understand how the RSA process and the resulting suggestions for improvement fit into the planning process for each agency, region, and/or State. Through partnerships, many DOTs have created formal initiatives with FLMAs and Tribes to ensure that each agency’s interests are addressed through the planning process while minimizing negative impacts or feelings by any party involved (see “Who should I partner with to integrate an RSA program in the planning process?”). It is also important that other local and regional stakeholders (e.g., MPOs and COGs) buy into the RSA process and realize the benefits of the suggested improvements so that the program gains support, relationships form and grow, and measures continue to be programmed.

This chapter summarizes the key points presented in the Toolkit, providing guidance regarding what can be done to move forward in establishing an RSA program and conducting RSAs. Further information related to the available references to aid in this process can be found in the Resource Materials section.

The following are key elements of starting an RSA program.

There are a number of supporting and participatory resources available to assist Federal and Tribal transportation agencies in improving safety by conducting RSAs. Resources are also available to provide updates on the “state of practice” for RSAs as well as information about safety issues and treatments being used by others. Several examples are provided as a starting point:

Keep in mind that implementing changes may take time. Even seemingly minor changes may require coordination with multiple agencies and may result in a change in policies or practices. However, by working together, positive relationships can be established that will provide longer-term benefits in all efforts to improve safety…all it takes is commitment.