U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Download Version

PDF [2.17 MB]

This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document.

The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement.

| 1. Report No. FHWA-FLH-10-05 |

2. Government Accession No. | 3. Recipient's Catalog No. |

||

| 4. Title and Subtitle Federal and Tribal Lands Road Safety Audits: Case Studies |

5. Report Date December 2009 |

|||

| 6. Performing Organization Code | ||||

| 7. Author(s) Dan Nabors, Frank Gross, and Margaret Gibbs |

8. Performing Organization Report No. | |||

| 9. Performing Organization Name and Address. Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc (VHB) 8300 Boone Blvd., Ste. 700 Vienna, VA 22182-2626 |

10. Work Unit No. | |||

| 11. Contract or Grant No. DTFH61-05-D-00024 |

||||

| 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Office of Safety 400 Seventh Street, SW, HSSD Washington, DC 20590 |

13. Type of Report and Period Covered September 2007- January 2010 |

|||

| 14. Sponsoring Agency Code FHWA/HSSD |

||||

| 15. Supplementary Notes. The Federal Highway Administration (Office of Safety and Office of Federal Lands Highway) sponsored six of the RSAs reported in this document. The FHWA Office of Federal Lands Task Order Manager was Chimai Ngo. The Office of Safety Task Order Manager was Rebecca Crowe. Documentation of the other two RSAs included in this document were provided by Victoria Brinkly and Scott Whittemore. Production was performed by Michelle Scism from VHB. |

||||

| 16. Road Safety Audits/Assessments (RSAs) are an effective tool for proactively improving the future safety performance of a road project during the planning and design stages, and for identifying safety issues in existing transportation facilities. To demonstrate the usefulness and effectiveness of RSAs on Federal and tribal lands,the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Office of Safety and Office of Federal Lands Highway sponsored a series of six Federal and tribal lands RSAs. Two additional RSAs on Federal Lands were conducted by Western and Eastern Federal Lands Division Offices. The results of the RSAs have been compiled in this case studies document. Each case study includes photographs, a project description, a summary of key findings, and the lessons learned. The aim of this document is to provide Federal Land Management Agencies (FLMAs) and tribal transportation agencies with examples and advice that can assist them in implementing RSAs in their own jurisdictions. | ||||

| 17. Key Words. Road Safety Audits, Road Safety Assessments, RSAs, Safety, Tribal, Federal Lands, Case Studies | 18. Distribution Statement No restrictions. |

|||

| 19. Security Classif. (of this report) Unclassified |

20. Security Classif. (of this page) Unclassified |

21. No. of Pages | 22. Price | |

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72) - Reproduction of completed pages authorized

Road Safety Audits (RSAs) are an effective tool for proactively improving the future safety performance of a road project during the planning and design stages, and for identifying safety issues in existing transportation facilities. Additional information and resources on RSAs are available on the web at http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa.

Information for the case studies reported in this document was gathered during a series of eight RSAs conducted throughout the United States between 2007 and 2009, involving Federal Land Management Agencies (FLMAs) (Pinckney Island and Savannah National Wildlife Refuges, Patuxent Research Refuge, Siskiyou National Forest, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, and Gifford Pinchot National Forest) and tribal transportation agencies (Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Navajo Nation, and Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians). The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the authors greatly appreciate the cooperation of these FLMAs and Tribes, as well as other participating agencies such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and state departments of transportation (DOTs), for their willing and enthusiastic participation in this FHWA-sponsored RSA series.

THE FHWA CASE STUDIES: PROMOTING THE ACCEPTANCE OF RSAs

FIGURE 1 - RSA PROCESS

FIGURE 2 - START-UP MEETING

FIGURE 3 - FIELD REVIEW

FIGURE 4 - RSA ANALYSIS SESSION

FIGURE 5 - PRELIMINARY FINDINGS MEETING

TABLE 1 - CASE STUDY RSAS

TABLE 2 - CRASH RISK ASSESSMENT

Road Safety Audits/Assessments (RSAs) are an effective tool for proactively improving the future safety performance of a road project during the planning and design stages, and for identifying safety issues in existing transportation facilities.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Office of Safety and Office of Federal Lands Highway commissioned a series of six Federal and tribal lands RSAs as part of a Task Order under FHWA Contract DTFH61-05-D-00024. The RSAs were conducted by Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. and Opus International. Two additional RSAs on Federal Lands were conducted by Western and Eastern Federal Lands Division Offices.

The results of the RSAs have been compiled in this case studies document. Each case study includes photographs, a project description, a summary of key findings, and the lessons learned. The aim of this document is to provide Federal Land Management Agencies (FLMAs) and tribal transportation agencies with examples and advice that can assist them in implementing RSAs in their own jurisdictions.

A Road Safety Audit/Assessment (RSA) is a formal safety performance examination of an existing or future road or intersection by an independent, multidisciplinary team.

Changes in roadway ownership, traffic patterns (which may be seasonal), and development around roadways often create conditions unanticipated in the original roadway design. RSAs, conducted by a team that is independent of the facility Owner and design team, address safety by a thorough review of roadway, traffic, environmental, and human factors conditions. By focusing on safety, RSAs make sure that safety does not “fall through the cracks.”

The RSAs followed the procedures outlined in the FHWA Road Safety Audit Guidelines document (Publication Number FHWA-SA-06-06). The procedures involve an eight-step RSA process discussed later in this case study document.

The multidisciplinary RSA Team is typically composed of at least three members, representing backgrounds in road safety, traffic operations, and/or road design, and members from other areas such as maintenance, human factors, enforcement, and first responders. Members of the RSA Team are independent of the operations of the road or the design of the project being assessed. The RSA team’s independence assures two things: that there is no potential conflict of interest or defensiveness, and the project is reviewed with “fresh eyes.”

RSAs can be conducted at any stage in a project’s life:

The eight RSAs conducted in this case study program are summarized in Table 1.

| FACILITY OWNERS AND OTHER RESPONSIBLE AGENCIES | RSA SITES | RSA STAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Maryland State Highway Administration (SHA), United States Department of Agriculture, Patuxent Research Refuge |

|

existing roads and proposed design |

| Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Wisconsin Department of Transportation |

|

existing roads and planned improvements |

| Navajo Nation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Phillips Oil Company, San Juan County, Utah |

|

existing roads |

| Pinckney Island and Savannah National Wildlife Refuges, South Carolina Department of Transportation |

|

existing roads |

| US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, Bear Camp Coastal Route |

|

existing roads |

| Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians |

|

existing roads |

| Cumberland Gap Tunnel Authority, Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, Tennessee Department of Transportation, and National Park Service |

|

existing roads |

| US Forest Service, Skamania County, Washington |

|

existing roads |

All participating FLMAs and tribal transportation agencies volunteered to be involved in this RSA program. Involvement in the case study program required the agencies to nominate the sites for the RSA project; provide the RSA Team with the materials (such as traffic volume and crash data) on which the RSA would be based; participate in the start-up and preliminary findings meetings; and contribute at least one Federal/tribal staff member to participate on the RSA team. The RSA teams were led by two experienced and independent consultants.

Information on each of these RSAs, including background, a summary of RSA issues, and a list of suggested improvements, is included in the Appendix

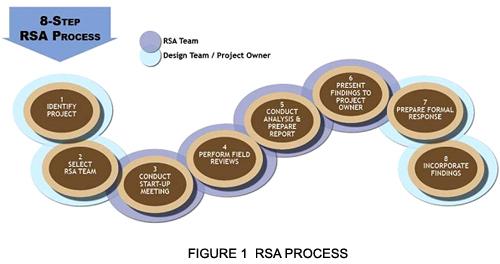

The eight steps of an RSA are shown in Figure 1, and are discussed below with some reference to the case studies.

RSA projects and the RSA Team (Steps 1 and 2) were pre-selected in this FHWA case studies project. RSA teams were interdisciplinary, typically including engineering and enforcement staff. Some RSA teams included non-traditional disciplines that were beneficial to the team, such as the public health specialist from Indian Health Services (IHS) who played a critical role in the Red Mesa RSA for the Navajo Nation.

All meetings and site visits for the RSAs in the case studies project were conducted over two or three day periods. The RSAs typically began with a start-up meeting (Step 3) attended by the Project Owner and/or Design Team (hereafter referred to as the Owner), and the RSA team:

|

|

Following the start-up meeting and a preliminary review of the design or site documentation, the RSA Team conducted a field review (Step 4). The purpose of the field review was to observe the ambient conditions in which the proposed design would operate (for the planning-stage RSA), or to observe geometric and operating conditions (for the RSAs of existing roads). The RSA Team observed site characteristics (such as road geometry, sight distances, clear zones, drainage, signing, lighting, and barriers), traffic characteristics (such as typical speeds and traffic mix), surrounding land uses (including traffic and pedestrian generators), and link points to the adjacent transportation network. Human factors issues were also considered by the RSA team, including road and intersection “readability,” sign location and sequencing, and older-driver limitations. Field reviews were conducted by the RSA Team under a variety of environmental conditions (such as daytime and night-time) and operational conditions (such as peak and off-peak times).

The team conducted the RSA analysis (Step 5) in a setting in which all team members reviewed available background information (such as traffic volumes and collision data) in light of the observations made in the field. On the basis of this review, the RSA Team identified and prioritized safety issues, including features that could contribute to a higher frequency and/or severity of crashes. For each safety issue, the RSA Team generated a list of possible measures to mitigate the crash potential and/or severity of a potential crash.

At the end of the analysis session, the Owner and RSA Team reconvened for a preliminary findings meeting (Step 6). Presenting the preliminary findings verbally in a meeting gave the Owner the opportunity to ask questions and seek clarification on the RSA findings, and also provided a useful forum for the Owner to suggest additional or alternative mitigation measures in conjunction with the RSA team. The discussion provided practical information that was subsequently used to write the RSA report.

|

|

In the weeks following the on-site portion of the RSA, the RSA Team wrote and issued the RSA report (also part of Step 6) to the Owner documenting the results of the RSA. The main content of the RSA report was a prioritized listing and description of the safety issues identified (illustrated using photographs taken during the site visit), with suggestions for improvements.

The Owner was encouraged to write a brief response letter (Step 7) containing a point-by-point response to each of the safety issues identified in the RSA report. The response letter identifies the action(s) to be taken, or explains why no action would be taken. The formal response letter is an important “closure” document for the RSA. As a final step, the Owner was encouraged to use the RSA findings to identify and implement safety improvements when policy, manpower, and funding permit (Step 8).

For many of the RSAs conducted on FLMAs and tribal lands, reliable crash data were not available. Anecdotal information on run off the road crashes and evidence of fence strikes along the roadway helped create a more complete picture of the potential hazards, but could not be quantified with any certainty. Therefore a prioritization framework was applied in both the RSA analysis and presentation of findings. The likely frequency and severity of crashes associated with each safety issue were qualitatively estimated, based on team members’ experience and expectations. Expected crash frequency was qualitatively estimated on the basis of expected crashes, exposure (how many road users would likely be exposed to the identified safety issue?) and probability (how likely was it that a collision would result from the identified issue?). Expected crash severity was qualitatively estimated on the basis of factors such as anticipated speeds, expected collision types, and the likelihood that vulnerable road users would be exposed. These two risk elements (frequency and severity) were considered during the qualitative risk assessment of each safety issue on the basis of the matrix shown in Table 2.

Consequently, the RSA Team prioritized each safety issue. It should be stressed that this prioritization method was qualitative, based on the expectations and judgment of the RSA Team members, and was employed to help the Owner prioritize the multiple issues identified in the RSA. For each safety issue identified, possible mitigation measures were suggested for short-term, intermediate, and long-term implementation timeframes. The suggestions focused on short-term and intermediate measures that could be cost-effectively implemented within likely budget constraints. Ultimately, implementation of the measures suggested in the RSA is dependent on project costs and financial constraints of the Owner.

FREQUENCY RATING |

SEVERITY RATING | |||

| Minor | Moderate | Serious | Fatal | |

| Frequent | Moderate-High | High | Highest | Highest |

| Occasional | Moderate | Moderate-High | High | Highest |

| Infrequent | Low | Moderate | Moderate-High | High |

| Rare | Lowest | Low | Moderate | Moderate-High |

Three main factors contribute to the cost of an RSA:

The RSA Team costs reflect the size of the team and the time required for the RSA, which in turn are dependent on the complexity of the RSA project. For the RSAs in this case studies project, the following cost components are noted:

For this case studies project, additional RSA Team costs were incurred in travel and time for RSA Team leaders, who are consultants traveling from out of town. However, typical RSAs would employ local team members, and consequently entail only minor travel costs.

The design team and owner costs reflect the time required for staff to attend the start-up and preliminary findings meetings, and to subsequently read the RSA report and respond to its findings. In addition, staff time is required to compile project or site materials for the RSA team.

The final cost component is that resulting from design changes or enhancements, which reflect the number and complexity of the issues identified during the RSA. Suggested design changes and enhancements, listed in the Appendix (Tables A.1 through A.8) for each of the RSAs conducted for this case studies project, have focused on low-cost improvements or countermeasures where possible. Suggested improvements for the RSAs focused on improved signing and pavement markings, minor or moderate geometric changes (such as added auxiliary lanes at intersections), gateway treatments, and barrier improvements.

The primary benefits of RSAs are to be found in reduced crash costs as road safety is improved. The costs of automotive crashes are estimated by the US Department of Transportation1 as:

Other benefits of RSAs include reduced life-cycle project costs as crashes are reduced, and the development of good safety engineering and design practices, including consideration of potential multimodal safety issues and integrating human factors issues in the design, operations, and maintenance of roads.

It is difficult to quantify the benefits of design-stage RSAs, since they aim to prevent crashes from occurring on new or improved facilities that have no crash record. However, when compared with the high cost of motor-vehicle injuries discussed above, the moderate cost of a design-stage RSA suggests that changes implemented from an RSA only need to prevent a few low- or moderate-severity crashes for an RSA to be cost effective.

The benefits of RSAs on existing roads can be more easily quantified, since pre-and post- improvement collision histories are available. As an example, the Road Improvement Demonstration Project conducted by AAA Michigan in Detroit and Grand Rapids (MI), which is based on RSAs of existing high-crash urban intersections and implementation of low-cost safety measures, has demonstrated a benefit-cost ratio of 16:1. Another example of data on the quantitative safety benefit of RSAs conducted on existing roads comes from the New York DOT, which reports a 20 to 40 percent reduction in crashes at more than 300 high-crash locations that had received surface improvements and had been treated with other low-cost safety improvements suggested by RSAs.

The South Carolina DOT RSA program has reported a positive impact on safety. Early results from four separate RSAs, following one year of results, are promising. One site, implementing four of eight suggested improvements, saw total crashes decrease 12.5 percent, resulting in an economic savings of $40,000. A second site had a 15.8 percent increase in crashes after only two of the thirteen suggestions for improvements were incorporated. A third site, implementing all nine suggested improvements, saw a reduction of 60 percent in fatalities, resulting in an economic savings of $3,660,000. Finally, a fourth location, implementing 25 of the 37 suggested safety improvements, had a 23.4 percent reduction in crashes, resulting in an economic savings of $147,000.

The most objective and most often-cited study of the benefits of RSAs, conducted in Surrey County, United Kingdom, compared fatal and injury crash reductions at 19 assessed highway projects to those at 19 highway projects for which RSAs were not conducted. It found that, while the average yearly fatal and injury crash frequency at the RSA sites had dropped by 1.25 crashes per year (an average reduction from 2.08 to 0.83 crashes per year), the average yearly fatal and injury crash frequency at the sites that were not assessed had dropped by only 0.26 crashes per year (an average reduction from 2.6 to 2.34 crashes per year). This suggests that RSAs of highway projects make them almost five times more effective in reducing fatal and injury crashes.

Other major studies from the United Kingdom, Denmark, New Zealand, and Jordan quantify the benefits of RSAs in different ways. However, all report that RSAs are relatively inexpensive to conduct and are highly cost effective in identifying safety enhancements.

The RSAs in this case studies project have been well received by all participating agencies. There are several key factors that contribute to a successful RSA, the most obvious of which is working together to identify and solve road safety issues. Through a cooperative and coordinated effort, Federal, tribal, state, and local agencies can partner to enhance safety on our nation’s roads. There are also many unique conditions associated with RSAs conducted on or near Federal or tribal lands. Several key factors and lessons learned from the RSA case studies are discussed in the following sections.

The key factors described in this section are basic principles that should be considered on all RSAs of all facilities.

The core disciplines on an RSA Team are traffic operations, geometric design, and road safety. Beyond these disciplines, all of the RSA teams in this case studies project included members who brought a range of backgrounds and specialties to the RSA, including:

In this series of pilot RSAs, RSA Team members were recruited from the Federal or tribal agency, state DOTs, local agency, local enforcement, and FHWA. Federal or tribal agencies considering their own RSAs may consider these agencies, as well as staff from other Federal agencies or Tribes with whom they establish a reciprocal relationship, when looking to staff RSA teams. When staffing a team, the RSA Team leader should remember that the RSA Team should be independent of the project or site being assessed, as far as possible. While consultation with local involved staff is necessary to gain an adequate understanding of the project or site, the RSA Team should be made up of members who have little or no prior involvement with the specific project or site.

As part of the RSA process, the team identified proposed improvements or measures already in place (prior to the RSA) that improve the safety of road users, such as paved shoulders, designated pedestrian/bicycle facilities, targeted traffic enforcement, educational campaigns, and institutional measures that provide ongoing support for transportation safety initiatives. Acknowledging proposed improvements and safety measures that have been implemented puts the RSA findings in an appropriate context, and acknowledges the efforts already done by the road agency to improve the safety of road users.

RSAs are conducted by an independent and multidisciplinary team. Each team member brings individual expertise and perspective to the RSA that they can pass along to their teammates. It is important to fully engage every team member to facilitate a free and open discussion of issues and suggested improvements, which will help ensure the success of the RSA.

The RSA for the Navajo Nation in Red Mesa included team members from the Navajo DOT, Navajo police, Utah DOT, BIA, Indian Health Services, FHWA, and San Juan County. All members provided useful insights during the RSA process and several team members commented on the benefit of listening to and learning from their teammates who were able to provide a different perspective of the safety issues and potential improvements. For example, the member from Indian Health Services learned about road safety issues from a highway design perspective, and in return, was able to educate the team on road safety concerns from a public health perspective.

All of the Federal and tribal RSAs included suggestions for improvements to address safety issues. An important consideration in identifying and implementing road safety improvements is funding. The federal government provides funding assistance for eligible activities through legislative formulas and discretionary authority, including some 100% federal aid programs and programs based on 90/10 or 80/20 (federal/local) matches. The RSA Team can obtain up-to-date information on funding opportunities by referring to the following resources and visiting the following websites:

The Tribal Highway Safety Improvement Implementation Guide advises that the implementation plan for a tribal highway safety improvement project (THSIP) or highway safety project will depend greatly on which funding sources the Tribes pursue, since each source has different program eligibility requirements. Some of the important government traffic safety-funding sources include:

Additional sources specific to each state may be available from the state department of transportation.

Over the course of the Federal and tribal lands RSA case studies project, the RSA teams identified eleven key elements that must be considered as agencies move forward with an RSA program.

At the RSA start-up meeting, a frank discussion of the constraints and challenges encountered in the design of the project, or operation of existing road, is critical to the success of the RSA. It is crucial that the RSA Team understand the trade-offs and compromises that were a part of the design process or the form of the present road. Knowledge of these constraints helps the RSA Team to identify mitigation measures that are practical and reasonable.

The RSA for the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa included team members from the Red Cliff transportation agency and the Wisconsin DOT. The RSA was conducted on a section of WIS-13 (a state route) through the Red Cliff community. The state built the roadway and is responsible for major improvements such as resurfacing, while the Tribe is responsible for maintenance activities such as signing and pavement markings. Prior to the RSA, both agencies had identified improvements for this section of road, but the improvements did not coincide. There were also several mid- to long-range improvements planned for the area (e.g., relocating existing casino and new housing developments). The RSA provided an opportunity to combine aspects of the plans from both agencies to address the identified safety issues and assign responsibility to the respective parties. The RSA Team obtained a clear understanding of the desires and responsibilities of both parties as well as the planned developments in the area.

There is a need for a high degree of coordination among the RSA Team on Federal and tribal lands because of the many agencies involved. Most of the roads assessed in this series of RSAs were under the joint jurisdiction of two or more road agencies at different levels, including:

When a road is under multiple jurisdictions, there are multiple interests involved. For example, FLMAs may have partial control over improvements (due to environmental and right-of-way constraints) even though they may not own or be responsible for maintaining the roadway. As such, it is important to identify ownership and jurisdiction, as well as the responsibilities of each agency on the team.

Although relations between the representatives from these agencies ranged from civil to friendly on all RSAs conducted in this series, these multiple layers can result in a large and unwieldy RSA team, and may result in conflict between members of the team. At the same time, the involvement of multiple agencies was a distinct advantage in some Federal and tribal lands RSAs where participants were able to call upon resources within multiple agencies to make the RSA outcome as successful as possible.

The RSAs on Savannah Wildlife and Patuxent Research Refuges included state-owned roadways that travel through Federal lands owned by the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). In these situations, the wildlife refuges do not own the roadways, but there are multiple voices of concern regarding any improvements to the roads. Environmental impacts are often a concern of the FLMAs, but there is also a concern for the safety of their visitors. In the case of the Savannah RSA, the Federal lands agency recognized the safety issues along the roadways within the refuge and helped to identify suggestions to improve facilities with minimal impact to the environment. The Patuxent Research Refuge has established an agreement with the state for certain maintenance responsibilities.

The RSA for the Navajo Nation in Red Mesa was conducted along N-35. The entire N-35 corridor north of US-160 is a Federal Aid Highway. The portion of the roadway from milepost 0 to milepost 18 is owned by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The Phillips Oil Company paved the section of N-35 from milepost 18 to milepost 23, but road ownership remains the Navajo Nation’s. Funding for reconstruction and maintenance of N-35 comes from several sources, including the Indian Reservation Roads Program (IRR), Congressional earmarks, and the BIA road maintenance program. The funding for road improvements is administered by the Navajo Region Division of Transportation (NRDOT) through the IRR Program within the Federal Lands Highway Program. Funding for road maintenance comes from the Department of the Interior (DOI) and is also administered by the NRDOT. They have contracted San Juan County to maintain much of the roads in the county, including N-35. San Juan County is responsible for signing, pavement markings, and roadside mowing. While the ownership of the roadway is very complex and can present challenges, there are also benefits of multi-agency involvement. For example, funding for reconstruction and maintenance are limited for an individual agency, but the agencies identified options for pooling resources to implement the suggested RSA improvements.

The RSA Team should be consistently positive and constructive when dealing with the facility Owner. Many problems can be avoided if the RSA Team maintains effective communication with the Owner during the entire RSA process (including the opportunities presented in the start-up and preliminary findings meetings) to understand why roadway elements were designed as they were, and whether mitigation measures identified by the RSA Team are feasible and practical. This consultation also gives the Owner a “heads-up” regarding the issues identified during the RSA, as well as some input into possible solutions, both of which can reduce apprehension (and therefore defensiveness) concerning the RSA findings.

The cooperation of the Owner is vital to the success of the RSA. An RSA is not a critical review of the Owner’s work, but rather a supportive review of the facility with a focus on how safety can be further incorporated into the existing facility or design. Cooperation between the RSA Team and Owner usually results in a productive RSA, since the RSA Team will fully understand the design issues and challenges (as explained by the Owner), and suggested mitigation measures (as discussed in advance with the Owner) will be practical and reasonable.

Support from the Owner is vital to the success of individual RSAs and the RSA program as a whole. It is essential that the Owner commit the necessary time within the project schedule for conducting the RSA and incorporating any improvements resulting from it, as well as the staff to represent the Owner in the RSA process (primarily the start-up and preliminary findings meetings).

The Cumberland Gap National Historic Park RSA included an examination of the Tennessee side approach to the Cumberland Gap Tunnel. This section is jointly owned by the Tennessee DOT and Kentucky DOT. The RSA process was enhanced by cooperation from the project owners. Specifically, the Tennessee DOT offered to conduct a speed study at a high crash location to evaluate if speeding was a factor in the crashes. In addition, the Tennessee DOT provided assistance by outlining their state process for performing RSAs and implementing improvements in their High Risk Rural Roads Program. The established RSA process allowed the RSA Team to better focus on other key elements of the RSA workshop such as the field investigation, crash data analysis, and safety measure selection.

Similarly, on the Patuxent RSA, Maryland State Highway Administration, the facility Owner, provided information on established RSA policies, procedures, and RSA report formats. This enabled the RSA Team to more effectively use their time to discuss issues and opportunities for improvement.

Wilson and Lipinski noted in their synthesis of RSA practices in the United States that the introduction of RSAs or an RSA program can face opposition based on liability concerns, the anticipated costs of the RSA or of implementing suggested changes, and commitment of staff resources. To help overcome this resistance, a “local champion” who understands the purposes and procedures of an RSA, and who is willing and able to promote RSAs on at least a trial basis, is desirable. Thus, measures to introduce RSAs to a core of senior transportation professionals can help to promote their wider acceptance. “Local champions” have been found within Federal and tribal road agencies, state DOTs, and FHWA field offices.

However, sometimes a local champion can emerge from a discipline other than the transportation field. For example, Indian Health Services (IHS) worked tirelessly to ensure an RSA was conducted for the Navajo Nation. Having detailed knowledge of the issues affecting the health and safety of people within their jurisdiction, IHS staff helped to identify potential RSA projects and RSA Team members to ensure maximum impact of the RSA.

Where possible, the RSA Team should visit the project site when traffic conditions are typical or representative. For example, the RSA for the Red Cliff community included the primary road through their community as well as a local road that provides access to residential areas. Pedestrian safety, particularly for school children, was identified as an issue along these roads. Therefore, the RSA Team scheduled site visits during the school year and observed conditions during the morning and afternoon, coinciding with the start and end of the school day. As such, the team was able to observe pedestrian, bicycle, and bus activity along the routes and identify suggestions to enhance safety for all road users.

In contrast, the RSA on the Navajo Nation was conducted in late August, nearing the end of the tourist season, but prior to the annual Shiprock Fair in October. The review of the crash data identified a substantial increase in crashes in October, coinciding with the Shiprock Fair. Consequently, the RSA Team was not able to observe traffic conditions and driver behavior associated with the annual event. Although this did not significantly affect the RSA findings, scheduling the field review to observe recurring traffic conditions is preferable as it allows the RSA Team to see how these traffic conditions and road user behavior may affect safety.

The RSAs conducted as part of this series all included field visits during various conditions (i.e., day/night and AM/PM peak periods). When possible it is also important to conduct field visits during various weather conditions. Conducting field visits under various roadway and traffic conditions allows the RSA Team to observe road user behaviors under each scenario and identify potential safety issues.

The Patuxent RSA was conducted during various conditions, including daytime, night-time, and wet weather conditions. Drainage issues, including standing water near inlets and ponding in wheel ruts, were apparent based on the field review during wet weather conditions. The RSA Team also reviewed the study area during night-time conditions, which helped to identify the lack of visual guidance as a major safety issue. These issues would not have been easily detected if the field review was conducted during daylight and dry weather conditions only. As a result of the field review under various conditions, the RSA Team was able to conduct a more comprehensive review and incorporate this information in their suggestions for improvements.

The Red Mesa RSA Team also identified safety issues during day and night conditions. During the day, the team noted several signs that were dirty. Under further review during nighttime conditions, the RSA Team noted that the same signs were nearly illegible. The nighttime review helped to identify the severity of the issue related to sign maintenance.

Tribal agencies are responsible for the roadways within their jurisdiction, but there is often a shared responsibility with the state DOT because state roads often border or pass through tribal lands. The state may be responsible for construction of the roadway, but the Tribe is often responsible for maintaining the roadway. This requires an effective line of communication between the involved parties. The RSA process involves a formal safety evaluation by a multidisciplinary team, and for RSAs on tribal lands, the team often includes representation from the local Tribe and state DOT, among others. This provides an opportunity for the Tribe to discuss their issues and long-term visions with the state DOT and vice versa. As such, RSAs not only have the potential to enhance road safety, they have the potential to help establish better lines of communication and cooperation between the state DOT and the Tribe.

The Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa is responsible for maintaining the signs and pavement markings on WIS-13 (a state route) through their community. During the RSA, it was discovered that the Wisconsin DOT and the Red Cliff Tribe had each identified improvements for WIS-13, but the two agencies’ plans did not coincide. The RSA process provided an opportunity for the agencies to establish a common vision for WIS-13 within the Red Cliff community and develop short-term, intermediate, and long-term goals. The RSA Team also identified safety issues on the existing facility and developed a list of additional improvements to include as part of the short-term, intermediate, and long-term goals. Overall, the RSA process provided an opportunity to enhance communication between the agencies and integrate planned improvements into a single vision. Throughout the course of the RSA process, the Red Cliff community, WisDOT, and BIA provided support and were open to suggestions for improvements. This attitude will help to maintain long-term communications and a commitment to improving safety for the Red Cliff community.

As part of the RSA opening meeting, the Team reviews data available for the study location such as traffic volumes and crashes. The RSA Team may also review long-range improvement plans. It is important for the RSA Team to understand the extent of the long-range plans so that they can identify how and when existing safety issues may be addressed. This also provides an opportunity for the RSA Team to identify additional improvements that were not previously identified in the long-range plans.

During the RSA for the Navajo Nation in Red Mesa, the RSA Team identified several safety issues related to the narrow roadway width and lack of shoulders. Due to the limited annual funding for maintenance and roadway improvements, it was not practical to identify pavement widening as a short-term or intermediate improvement. However, there is a long-term resurfacing project along the corridor and the RSA Team identified opportunities to incorporate RSA suggestions as part of this long-range project.

Current use of roadways on Federal and tribal lands often exceed the intended use for which they were designed. Several of the RSAs conducted as part of this case studies series included roads that were designed for low-volume, passenger car use. As such, the lane and shoulder widths are relatively narrow and roadsides are often unforgiving. Due to local attractions (e.g., National parks) that are served by these roadways or the location of these roads in relation to commuter routes, there are increasing traffic volumes along these routes.

The original purpose of Bear Camp Road in Oregon was for timber haul and for administration of Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management lands. However, the use and function of the road has evolved over time. At the time of the RSA, the road was being used by the public as a link between the interior of Oregon and the coast, and for commercial and recreational uses. Although the use and function of the road has evolved, its design, maintenance, and management has not. Consequently, the public was using a facility that was not designed for public use, and that did not incorporate safety features that the public generally expects or assumes.

The RSA for the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge in South Carolina included the review of a two-lane, rural road with limited lane widths and no paved shoulders. Pedestrian and bicycle activity along this route is generated by the refuge wildlife trails. The refuge would like to encourage further pedestrian and bicycle activity, but there are currently inadequate facilities along the roadway (i.e., no paved shoulders). This road also serves local traffic as well as large truck volumes from nearby factories, mills, and the Savannah Port. The truck volumes are expected to increase substantially when the Jasper Port opens. The mix of heavy truck traffic with pedestrians and bicyclists, coupled with limited geometrics, creates a significant safety concern.

The RSA in Red Cliff, Wisconsin included a section of WIS-13 through the Red Cliff community. While this road is a rural state trunk highway, it is a two-lane road with narrow shoulders and relatively high speeds. The route serves commuters between the communities of Bayfield and Red Cliff and also accommodates tourist traffic visiting local attractions such as the Isle Vista Casino, Town of Bayfield, and the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore (National Park). While pedestrian, bicycle, and ATV activity are generated by several nearby attractions, there are limited facilities to accommodate these user groups. The RSA Team identified options to create more of a community feel to the section of road through the Red Cliff community to help increase driver expectancy of pedestrians and bicyclists and potentially reduce vehicle speeds. The Team also identified opportunities to construct shared-use paths for pedestrians and bicyclists along the route.

The RSA for the Patuxent Research Refuge included a portion of Laurel Bowie Road. The road was constructed as a two-lane rural road, serving the Patuxent Research Refuge with several access points to the Refuge in the study area. The roadway has since become a heavily traveled commuter route between Laurel and Bowie. The roadway and roadside were not designed to accommodate the current use of the facility, which has manifested in a safety problem, including several fatal crashes.

There are multiple pedestrian and bicycle generators on Federal and tribal lands, but often a lack of adequate pedestrian and bicycle facilities. WIS-13 in Red Cliff, Wisconsin not only serves local pedestrian, bicycle, and vehicle traffic, but also accommodates tourist traffic generated by the Isle Vista Casino and Apostle Islands National Lakeshore (National Park). There are limited shoulders and no sidewalks for pedestrians and bicyclists along WIS-13. Coupled with relatively high vehicle speeds, this creates a significant safety issue for pedestrians and bicyclists.

The Savannah Wildlife Refuge generates significant pedestrian and bicycle activity, particularly along SC-170, which provides access to a wildlife viewing trail. Many visitors currently drive to the beginning of the Laurel Hill Wildlife Drive, park their vehicle, and continue by bike along the 4.5 mile drive. At the end of the drive, the bicyclists must either ride along SC-170 to return to their vehicle or backtrack the 4.5 miles against traffic on the one-way wildlife drive. The lane widths are narrow and there are no paved shoulders on SC-170. Coupled with the increasing volumes of heavy trucks, this creates an unsafe situation for pedestrians and bicyclists. The RSA Team identified several options for improving pedestrian and bicycle facilities within the refuge.

Animal-vehicle crashes vary by state and region. Deer are a primary concern in many states, but moose, elk, cows, and horses are a significant safety concern in Federal and tribal lands. There is a significant safety concern for motorists when the animals are large because crashes are often more severe. Animal-related crashes can be classified as wildlife or as domestic/livestock. The safety concerns may be similar among the two groups (i.e., large animals create a significant risk); however, the countermeasures to address the two categories can differ.

There are no assigned “keepers” of non-domestic animals (i.e., wildlife). Wildlife may travel long distances for food, mating, and migration. These animals often cross many roads in their travels. While animal fencing is an effective method for reducing animal crossings, it interferes with the animals’ desired route and disrupts their feeding, mating, and migration. The Deer-Vehicle Crash Information Clearinghouse identifies several countermeasures to address deer-vehicle collisions (http://www.deercrash.org/toolbox/). Many of these strategies can also be applied to address other types of animal crashes. For example, wildlife crossings (i.e., overpasses and underpasses) are identified as a strategy to address deer collisions, but have been constructed in many states to provide safe crossing routes for several other species ranging from frogs to bear. FHWA has developed a document and a website specifically focused on wildlife crossings or “critter crossings” as they are also known (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/wildlifecrossings/).

Domestic animals and livestock are also a safety concern, but someone is responsible for these animals. The risk of animal-vehicle collisions increases when domestic animals and livestock are allowed to roam free along the roadway. Installing and maintaining fencing along the road can help to reduce the number of animal-related crashes. However, it may be too costly for some agencies to install and maintain animal fencing. While enforcement and education efforts are not particularly useful to address wildlife crashes, they can help to address crashes related to domestic animals and livestock. Specifically, laws can be enacted and enforced to prohibit grazing within the right-of-way. Education campaigns can be employed to provide information related to animal control laws and stress the importance of keeping animals and drivers safe by minimizing potential conflicts.

Open grazing is allowed along N-35 on the Navajo Nation in Red Mesa, Utah. Coupled with a lack of animal fencing, animal crashes represent approximately 25 percent of crashes annually along the corridor. The Patuxent Research Refuge has animal fencing along the road to control animals and, as such, animal crashes are not a significant issue. The animal fence on the Patuxent Research Refuge is often struck, but these crashes are often much less severe than animal crashes and the fence is easily repaired. The fence collisions are partially attributed to roads that are not designed for current traffic use and non-recoverable slopes that lead to the fence.

The Federal and tribal lands RSA case studies project sponsored by the FHWA Office of Federal Lands Highway and the Office of Safety has been well received by the participating FLMAs and tribal transportation agencies. The case studies project has exposed FLMAs and tribal governments to the concepts and practices of an RSA, and provided the opportunity for these agencies’ staff members to participate on the RSA Team as part of the process. This case studies document has summarized the results of each RSA, with the intent of providing FLMAs and tribal governments with examples and advice to assist them in implementing RSAs in their own jurisdictions. While safety issues vary from one transportation facility to another, these case studies provide a wide range of examples that demonstrate the usefulness of RSAs in solving safety problems on Federal and tribal lands.

Pinckney Island and Savannah Wildlife Refuges, South Carolina

Patuxent Research Refuge, Maryland

Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Wisconsin

Navajo Nation, Utah

Siskiyou National Forest, Bear Camp Coastal Route, Oregon

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, North Carolina

Cumberland Gap National Historic Park, Tennessee

Gifford Pinchot National Forest, US Forest Service, Washington

¹ Intersection Safety Issue Brief No. 15 (“Road Safety Audits: An Emerging and Effective Tool for Improved Safety”), issued April 2004 by Federal Highway Administration and Institute of Transportation Engineers.

² Eugene Wilson and Martin Lipinski. NCHRP Synthesis 336: Road Safety Audits, A Synthesis of Highway Practice (National Cooperative Highway Research Program, TRB, 2004)