U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

FHWA Course on Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation

Slideshow for Instructors' Use

Slideshow Script: Bicycle and Pedestrian Planning and Design

- Powerpoint Word Slide (title): Bicycle and Pedestrian Planning and Design

- Powerpoint Word Slide: Why should we accommodate bicycles and pedestrians?

- Bicycles are legally considered to be vehicles, with the right to use

roadways

- There are 9 million bike trips and 56 million walking trips in the

U.S. everyday

- One in ten U.S. households do not own an automobile

- 1/3 of the population do not drive an automobile

Explanation:

(Go through each bullet, elaborate on bullet #3) A sizeable number of

US citizens do not drive because they are too young, or are adults who

for whatever reason do not choose to drive (perhaps due to a disability

or by choice), or are elderly citizens who are no longer able to drive.

References: References: Uniform Vehicle Code, 1995 National Personal Transportation

Survey (NPTS), 1990 US Census

- PowerPoint Word Slide: More reasons:

- There should be other options than driving for short trips

- Better environment

- reductions in air pollution and traffic congestion

- decreased need for roadway infrastructure; less stormwater runoff;

land would be conserved

- PowerPoint Word Slide: And still more reasons:

- Better health: 60% of Americans lead completely sedentary lifestyles,

40% are clinically overweight

- Improved safety: 6000 bicyclists and pedestrians killed and 125,000

injured per year (1996 figures)

References: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1998 American

Medical Association Report

- PowerPoint Word Slide: Federal Goals for Bicycling

- Set by USDOT in National Bicycling and Walking Study (1994):

- Double the percentage of total trips made by bicycling and walking

(from 7.9 to 15.8%)

- Simultaneously reduce by 10% the number of bicyclists and pedestrians

killed or injured in traffic crashes

- PowerPoint Word Slide: Federal Legislation

- ISTEA – Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (1991)

- TEA 21 – Transportation Equity Act of the Twenty-First Century

Explanation:

Bicycle and pedestrian facilities are eligible for funding through the

Enhancements program, which (in both ISTEA and TEA-21) sets aside 10%

of federal Surface Transportation funds for ten categories of "enhancements"

which also include scenic byways, historical transportation facilities,

etc.

Reference: FHWA-P1 98-049: A Summary: Bicycle Pedestrian Provisions of

the Federal – Aid Program

- Powerpoint Word Slide:

Spending on Bike/Ped Facilities: Pre-ISTEA and During ISTEA

- Pre-ISTEA: $4 million/year nationwide

- During ISTEA: $160 million/year nationwide

Reference: Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

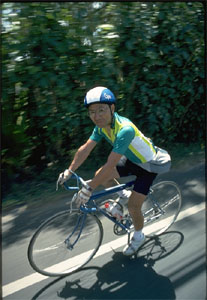

- Photo Slide: Advanced bicyclist

Explanation:

There are different types of bicyclists with various skill levels. In general,

they fall into several categories. This is a "Type A" advanced

bicyclist. These are people who ride regularly – confident, strong riders.

They are generally accustomed to riding in traffic, but many will still

avoid the worst roadways. They are interested in direct routes (for utilitarian

riders) and/or scenic routes (recreational riders).

- Photo Slide: Basic bicyclists

Explanation: There is a very large group (the majority) of bicyclists who

aren't as confident in their bicycling skills, but still enjoy riding. Traffic

conditions are quite daunting to this group, however they also represent an

enormous potential for reducing auto trips if bicycling conditions were better.

These are referred to as "Type B" bicyclists.

Type B bicyclists may also ride for utilitarian purposes. This group also

includes many low income Americans who ride for purely economic reasons – they can't afford an automobile.

- Photo Slide: Child bicyclist

Explanation:

Child bicyclists or "Type C" cyclists are the last group. Their

riding is initially monitored by parents. They may have all the confidence

of Type A riders, but lack coordination and judgment when it comes to traffic

conditions.

- Powerpoint Word Slide: Designing Bicycle Facilities: Policies and Standards

- Federal

- U.S. Access Board – Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility

Guidelines

- FHWA – Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD)

- AASHTO – Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities

- State and local manuals

- Example: Oregon DOT Bicycle and Pedestrian Plan

- PowerPoint Word Slide (title): Types of Bicycle Facilities

- Photo Slide: Shared Roadway

Explanation: Since the bicycle is considered a vehicle with the legal right

to use most roadways (except limited access freeways in some states), all

roadways are shared roadways.

- Photo Slide: Wide outside lane

Explanation: By adding just a few feet of width, roadways can accommodate

bicyclists effectively. This photo shows a wide outside lane – 14' in width

instead of the normal 12'. Both the bicyclist and motorist can occupy the

same lane. The downside is that motorists tend to travel faster in a wide

lane, and this makes bicyclists more uncomfortable. You have to be careful

when you design this type of facility – outside lanes that are too wide (i.e.

15' or 16') can result in two cars operating in one lane.

- Photo Slide: Paved shoulder

Explanation:

By striping additional space on the edge of the road to create a shoulder

you can improve a bicyclist's sense of comfort. A four-foot to ten-foot wide

shoulder is preferred (given the traffic volumes and speed of traffic along

the corridor in question), however according to the AASHTO Guide for the

Development of Bicycle Facilities, any additional width is better than

none at all.

- Photo Slide: Bike route

Explanation: In some cases, the road is already in good condition – quiet,

with low speeds and traffic volumes. Bike routes can be designated on these

streets if they are part of a network of facilities. Bike routes are described

in the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities as being "signed

shared roadways." The Guide states that the "signing of shared

roadways should indicate to bicyclists that particular advantages exist to

using these routes compared with alternative routes. This means that responsible

agencies have take actions to assure that these routes are suitable as shared

routes and will be maintained in a manner consistent with the needs of bicyclists."

In other words, bike route signs should not be placed on roadways with hazardous

conditions or sudden, unexpected obstacles such as narrow bridges or unsafe

drain grates.

Green bike route signs are also often used in rural areas for bicycle touring

routes.

- Photo Slide:

Explanation: Bike lanes are typically 5' in width (4' minimum if there is

no curb) with marking and signs (standardized by MUTCD) that define the space

as a bike lane. They are always on both sides of the street, and travel in

the same direction as the adjacent travel lane.

- Photo Slide: Bike lane ending/transition

Explanation:

Provide advance warning that the bike lane will end ahead, use appropriate

pavement markings to signal the end of the lane. If necessary, end lanes

in a location where the bicyclist would have the option to turn onto a side

street, if traffic conditions ahead are particularly bad.

This example has good and bad points. This bike lane is in Philadelphia.

A sign a couple hundred feet back warns that the end of the lane is near,

and there are good sight lines in this location so motorists can see merging

bicyclists ahead. The merge location is shown with a dashed line. It could

be made better by making the merge area less abrupt by starting the dash further

back to encourage bicyclists to merge earlier. It would also be beneficial

to place a wide curb cut at this location to enable less experienced bicyclists

to get off the road here, if necessary.

- Photo Slide: Contra-flow lane

Explanation:

Innovative solutions that are not currently in the MUTCD but are currently

being explored in Europe and the US: contra-flow lanes on one-way streets

can sometimes be warranted, particularly if they provide a route for bicyclists

that is shorter or avoids a difficult traffic situation. There should always

be a double yellow line between the bike lane and the motor vehicle lanes,

and signing should be used to make it clear that bicycles – and not automobiles

– are allowed in this direction. Care should be taken to ensure that contra-flow

lanes do not have confusing pavement markings or other traffic control devices.

- Photo Slide: Blue bike lanes

Explanation:

Another innovative solution that is not currently in the MUTCD: blue bike

lanes have been used in Europe and in parts of the United States to draw attention

to bike lanes and to discourage motorists from encroaching upon them. Motorists

may be unaware that it is illegal to drive and park in bicycle lanes. Even

more critical, they are unaware of the need to yield to cyclists when crossing

a bicycle lane to turn right or get into a right-turn only lane. The result

of this is a relatively high level of conflicts in these areas—both in terms

of crashes and "near misses."

In the U.S., a number of communities have experimented with colored bike lanes.

These photographs were taken in Portland, Oregon, as part of a two-year study

the City of Portland (with assistance from FHWA) conducted on blue bike lanes

in locations that had weaving problems between bikes and cars. The study found

that motorists appear to yield more frequently to bicyclists after the blue

bike lanes were installed, and more motorists tended to stop or slow down

when approaching the conflict areas. Bicyclists, however, were found to decrease

head turning and hand signaling, although they were more likely to use the

recommended path across the conflict area. Overall, the number of conflicts

decreased with the use of blue bike lanes in these areas.

- PowerPoint Word Slide (title): Other Barriers and Roadway Hazards Affecting

Bicyclists

- Photo Slide: Unsafe grate

Explanation:

Drain grates parallel to travel can catch a bicycle wheel and cause a major

crash. Grate openings should be perpendicular to travel. Some cities have

instituted programs to locate and replace all unsafe grates.

- Photo Slide: Railroad crossing

Explanation:

Railroad and light rail crossings create rough, uneven conditions. Bicycles

are much more susceptible to these surface irregularities because they have

no suspension. A rough railroad crossing can not only cause permanent damage

to a bicycle, it can cause the bicyclist to lose control and crash. This

photo shows an improved crossing – smoother for both motorists and bicyclists.

Railroad crossings that are at an acute angle can be particularly bad, since

a bicycle tire can get caught between the edge of the rail and the edge of

the pavement.

- Photo Slide: Recessed manhole cover and grate

Explanation:

Surface irregularities can often be worse in CBD's and urban downtown areas

where the streets have been repaved and patched many times. Manhole covers

and inlet grates should always be raised during repaving projects, rather

than leaving them at their former height. Notice that in this photo on the

left, the manhole covers were raised, but the inlet grates were not.

Designers should also be aware that rumble strips on shoulders can result

in operational problems and safety hazards for bicyclists. The benefits of

rumble strips should be carefully weighed against the problems they cause

for bicyclists. The AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities

recommends that, if rumble strips are absolutely necessary, a minimum of 4

feet of pavement width to the right of the rumble strip should be provided

for bicyclists. In the photo on the right, the total width of the shoulder

is only about 5 or 6 feet, and about a third of that space is taken up by

the rumble strip. Therefore, this is not a good example since the shoulder

does not provide 4 feet of width for the bicyclist.

- Photo Slide: Loop marking

Explanation:

At actuated signals, loop detectors in the pavement are designed to react

to the presence of a motor vehicle – and are often not sensitive enough to

detect the smalldisturbance in the inductance field created by a bicycle.

So unless an automobile pulls up, a bicyclist may not be able to get a green

light.

One solution is to find the spot along the loop wire that is most sensitive

(i.e. the location a bicycle should stand in order to trip the signal). A

special marking should be placed on that spot so that bicyclists can find

it. Unfortunately, this doesn't always work. Many of the newer metal loops

are not tuned sensitively enough to detect a bicycle, or the detectors may

not be working.

The Traffic Detector Handbook (published by the Institute of Transportation

Engineers) recommends a quadruple loop detector for bike lanes. It should

be placed directly in the bike lane to insure that bicycles can trip the signal.

- PowerPoint Word Slide (title): Other Programs and Facilities that Benefit

Bicyclists

- Photo Slide: Bike on bus rack

Explanation:

Bike on transit programs can greatly expand the service area for transit programs.

Many cities and towns in the U.S. are instituting these programs, and have

been very successful. Racks are usually installed on the fronts of buses,

and hold two bikes. Bike-on-Rail programs have also become popular (transit

agencies allow riders to bring their bikes aboard, sometimes providing special

cars with extra storage space. In some cities, this service is limited to

non-peak hours.

- Photo Slide: Bike to Work Day, Philadelphia, 1998

Explanation:

Bike-to-Work Day is an annual event held in the spring in the U.S. Most major

cities host an event or a week of events (Denver hosts a Bike-to-Work month).

There are a variety of commuter incentive programs that have been used across

the country to encourage bicycle commuting, including cash incentives, premium

bike parking facilities (sometimes inside the building), shower facilities,

flexible working hours, "free ride home" programs in the event of

an emergency, and bike maintenance on-site.

- Photo Slide: Bike rack

Explanation:

Most cities lack adequate bike parking. This can be a disincentive to bicycling

– both because of the inconvenience and because bicycles that aren't locked

to a sturdy structure may very likely be stolen. Bike racks should be simple

in design, and should support the frame of the bike (not just the wheel).

This is a slightly modified version of the popular U-rack.

- Photo Slide: Kids learning bike skills

Explanation:

There are a number of bicycle education programs for children and adults.

Several curricula for children are available. They work best when they combine

classroom instruction with on-bike training. More and more colleges and universities

are offering bicycle training courses. Another national bicycle education

program for adults is the Effective Cycling program (contact the League of

American Bicyclists in Washington).

- Powerpoint Word Slide (title): Pedestrian Planning and Design Issues

- Photo Slide: Aerial view of residential cul-de-sac development/residential street

Explanation:

Zoning and subdivision development practices have had a tremendous effect

on pedestrian and bicycle mobility. This is what most U.S. suburban residential

developments look like today. Of course, the history of transportation and

land use in this country can provide an explanation for why our communities

no longer encourage or accommodate pedestrians. During the Industrial Revolution,

single-use zoning was introduced in order to buffer residential areas from

unpleasant and noxious adjacent land uses. As automobiles became more commonly

used for transportation and the streetcar was phased out, houses moved back

from the street. People began to use automobiles to reach more and more destinations,

even those that were close to home. As traffic became a problem, cul-de-sacs

were developed to reduce through-traffic on residential streets. This is

the result: enclaves of housing that are separated from commercial areas by

high speed, heavily traveled arterial roadways.

Unfortunately, suburban residential areas have lost the character that they

once had. Houses all look the same – often the garage is the most prominent

thing on the front of the house. There are no sidewalks or street trees,

and the streets are extremely wide.

- Photo Slide: Residential street – Birmingham, AL

Explanation:

It wasn't always this way. Older communities were designed to be far more

pedestrian-friendly, because people relied so much more on walking (people

actually walked to the store and other destinations). Older developments tended

to have a mixed land use of commercial and residential properties. This is

now some of the hottest real estate in the U.S.

- Photo Slide: Arterial through a strip developed area

Explanation:

The result of our land use and transportation policies over the past 50 years

has been to create shopping districts that look like this. People can't walk

between adjacent developments because of fences, ditches, hedges and other

barriers. There are a variety of barriers to walking in this photograph –

besides just the physical discomfort of walking next to seven lanes of traffic,

pedestrians also must get around the light poles which are located in the

center of the sidewalk, the lack of any accommodations at intersections to

enable pedestrians to comfortably cross, and many other physical barriers.

- Photo Slide: Wide intersection on arterial road

Explanation:

Some intersections are vast, and are timed for optimum traffic flow. Crosswalks

do not solve the problem of getting a pedestrian across the street if one

has to cross 120' of pavement and the signal phasing does not adequately accommodate

pedestrians. Four feet per second walking speed is average, however there

is a trend to use slower walking speeds (such as 3 - 3.5 feet per second)

in order to better accommodate older people and people with disabilities.

At 4 feet per second, the pedestrian phase would be 30s (WALK plus flashing

DON'T WALK). At 3 feet per second, the pedestrian phase would be 40s (WALK

plus flashing DON'T WALK).

There are several important things to remember when designing intersection

signals:

- Consider your audience: do you anticipate a fair number of pedestrians

who may walk at a slower speed?

- Crosswalks and medians should be located so that pedestrians can use

the median as a refuge area, in the event that he or she is unable to

make a complete crossing and has to wait in the middle.

Another thing to think about: do you think an older person with declining

vision will be able to see the pedestrian signal head on the other side of

this intersection?

- Photo Slide: Downtown street

Explanation:

There is a trend towards revitalizing downtowns and making new commercial

development more closely resemble the pedestrian-friendly shopping districts

of earlier times. Trees, landscaping, and human-scale lighting not only enhance

the street, they provide a physical and psychological buffer between the pedestrians

and traffic.

- Photo Slide: Renovated commercial development (FL)

Explanation:

Communities have also begun to provide incentives to developers to renovate

older commercial strip centers. There are some excellent success stories.

For example, an older commercial development in Florida (picture on the left)

was renovated to look like this (picture on the right). Narrow streets, decorative

sidewalks, landscaping buffers and human scaled lighting make this street

more pedestrian-friendly.

- Photo Slide: Neotraditional neighborhood - Abacoa, FL

Explanation:

Neotraditional neighborhood design (also called new urbanism) is a "new"

style of community design that uses design principals from 18th

and 19th century American and European towns. Land uses are more

compact and mixed, creating the potential for short walking trips. The architecture

in many of these neighborhoods is often traditional, with wide front porches

and garages out back, connecting to streets via alleyways (thereby eliminating

driveways in front of the houses). Streets are narrower, and arranged in

a grid pattern to disperse vehicular traffic. Wide sidewalks and street trees

are on both sides of the road.

- PowerPoint Word Slide (title): Accommodating Pedestrians with Disabilities

- Photo Slide: Woman with cane on a sidewalk

Explanation:

It is important to understand the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990,

and how this law influences pedestrian facility design. The ADA has greatly

improved sidewalk design and is the reason why more and more sidewalks and

public spaces are barrier-free. ADA not only improves conditions for disabled

pedestrians, but makes sidewalks and intersections better for all users.

ADA is a comprehensive civil rights law that covers employment, education,

housing, communications, health care and transportation. The ADA requires

that the transportation system be accessible and barrier free to all people

with disabilities. A barrier free pedestrian system is particularly important

to people with disabilities because other forms of transportation may not

be optional or available. A barrier free system for a person using a wheelchair

is free of physical obstacles, and for a person who is blind, accessible information

such as audible signals and detectible warnings at intersections.

- Photo Slide: Group of people, some with disabilities

Explanation:

Besides the fact that the Americans with Disabilities Act is a law, why do

we want to design pedestrian facilities so that they accommodate people with

disabilities? Because it is estimated that approximately 70% of all Americans

will have a disability at some point in their lifetime, either temporarily

or permanently. Modern medicine has enabled more people with disabilities

to lead longer lives, and when you add that to the fact that the American

population is aging, you can see why this is so important. Odds are, most

of us in this room will experience some type of disability in the future.

Reference: Washington Department of Transportation

- PowerPoint Word Slide:

Sidewalk Design

- Minimum width: 5' (per AASHTO)

- Minimum clear path of travel (with no obstructions): 36"

- Desired running slope: no more than 5%

- Maximum grade of a ramp: 8.3%

- Maximum cross slope: 2% Firm, smooth, slip resistant surfaces

Explanation:

Sidewalk design is influenced heavily by ADA and AASHTO - the U.S. has finally

begun the process of standardizing sidewalk design, much in the same way as

we have standards for roadway design. The Americans with Disabilities Act

is the legal foundation for the Access Board's Accessibility Guidelines – they define basic design practices that enable people with disabilities to

be able to travel on foot or by wheelchair. Since the ADA is law, these design

guidelines carry quite a bit of weight. The list in this slide provides just

a few of the most basic sidewalk design principals.

(Additional explanation for third and fourth bullets)

Accessibility guidelines recognize that sometimes it is not possible to meet

these slope requirements along public sidewalks and shared-use paths, where

running slope is tied to roadway gradient and underlying terrain. Still,

running slope should be kept to the minimum feasible, since steep slopes have

an extremely detrimental effect on people with disabilities.

- Photo Slide: Sidewalk next to highway/Sidewalk with street trees

Explanation:

Sidewalks are certainly a critical first step in accommodating pedestrians,

but a lot of other design features are important if you want to encourage

walking. (Case in point – the sidewalk on the left provides a place for people

to walk, but very few people would feel comfortable in this location.) You

need to provide pedestrians a sense of protection from the adjacent roadway.

There are a number of ways to do this:

It is amazing how different a sidewalk feels with street trees. They serve

as a very effective buffer from traffic when they are located in the grass

strip between the sidewalk and the curb. This requires a minimum of a 5'

planting strip, although wider planting strips may be needed on roadways with

faster vehicle speeds. The choice of tree species is important - shade trees

are far more effective than small ornamental tree. Trees that branch from

the bottom or shrubs that are too tall can cause a sight distance problem:

the motorists may not see the pedestrian and vice versa.

Although trees have been shown to provide amount of comfort to the pedestrian,

there are some trade-offs. They require space, which is sometimes very limited

in urban areas. You also need to consider the functional class of the roadway

– trees can pose roadside hazards if they are too close to a high speed roadway.

- Photo Slide: Sidewalk 20' off edge of the road/ Sidewalk next to parking

lane

Explanation:

Pedestrians need a sense of protection from the adjacent roadway. There are

a number of ways to do this: A wider separation between the street and sidewalk

can also improve pedestrians' sense of comfort (left slide). Parking lanes

provide a very effective buffer between pedestrians and traffic (right slide).

- PowerPoint Word Slide (title): Intersection Design for Pedestrians

- Photo Slide: Aerial of large urban intersection

Explanation:

Intersections are the most challenging aspect of pedestrian facility design.

A variety of improvements could make this intersection safer for pedestrians..

Can you list all the things that are make this intersection difficult for

pedestrian crossings?

- Vast distances to cross (80' to 100'), and possibly not enough time

to make it because signals aren't timed for pedestrians.

- Right turn slip lanes - right turning traffic may not be required to

stop

- Some older pedestrians or pedestrians that are visually impaired can't

see traffic signals to know when they can get across

- Visibility problems: sign poles, utility boxes, etc. block visual access

between motorists and pedestrians.

- Fast turning traffic: corner turning radii are wide, making it easy

for motorists to maintain higher speeds when turning.

- Crosswalk markings are only on two legs of the intersection. How does

the pedestrian get to the south quadrant?

- Crosswalk is not near the median, denying the pedestrian of a refuge

from traffic while crossing.

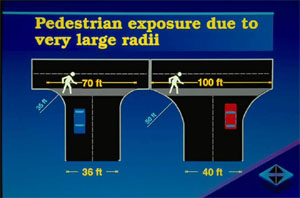

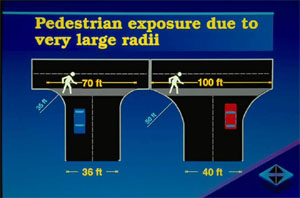

- PowerPoint Graphic Slide: Pedestrian exposure due to very large radii

Explanation:

Intersection solutions: create narrower distances for pedestrians to cross

at intersections. One way is to design corner curb returns with a tighter

radius. This also has the effect of slowing down turning traffic. One must

also consider the amount of heavy trucks that use the intersection – since

they may ride over the curb if the radius is too tight.

- Photo Slide: Pedestrians starting to cross intersection

Explanation:

Designers have typically used an average walking speed of 4' per second in

designing pedestrian accommodations, specifically in signal timing, at intersections.

There is a growing tendency to use 3.5' per second, or 3' per second to accommodate

older adults, school children, and people with disabilities. By using slower

walking speeds in intersection design, it allows for a longer green time (crossing

time) for pedestrians.

- Photo Slide: Aerial shot of intersection with curb bulb-outs

Explanation:

Another solution is to build curb extensions (also called bulb-outs) that

narrow the distance across the intersection. This is an example of a curb

extension that has been combined with decorative crosswalks to enhance pedestrian

visibility.

- Photo Slide: Medians and pedestrian refuge islands on an arterial

Explanation:

Medians and pedestrian refuge islands allow pedestrians to cross one direction

of traffic at a time, and provide a protected waiting area prior to getting

across the next segment. This is a good solution for large urban intersections.

Intersections on heavily traveled urban corridors are often timed in sequence

to reduce traffic backups, therefore it may be difficult or impossible to

create one signal phase long enough for pedestrians to cross the entire width

of the intersection without causing other parts of the system to fail.

Median refuge islands should have a curb cut on the island so that a person

in a wheelchair can pass through (36" minimum). If the cut is too wide,

a blind cane user may not be able to detect it, thus not know there is a refuge.

- Photo Slide: Aerial view of continental-style crosswalks

Explanation:

Some types of crosswalk markings are more visible than others and can help

to draw attention to pedestrian crossings. The continental-style crosswalk

can be used when a high level of visibility is desired. This style as well

as the ladder and zebra marking styles are known as high-visibility crosswalks.

This style of crosswalk also offers good contrast for people with low vision.

- Photo Slide: Pedestrian yellow-green warning sign

Explanation:

Warning signs can help, too. Keep in mind that they are often ignored by

motorists and, like crosswalks, should be used in conjunction with other pedestrian

improvements at intersections. This is a new sign that is being used in more

and more locations in the U.S. – it's a standard Pedestrian Warning sign (W11-2)

with a bold fluorescent yellow/green color.

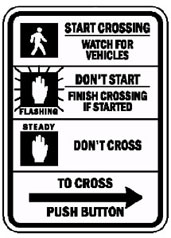

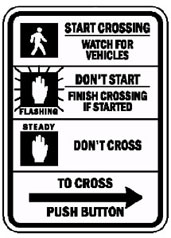

- Photo Slide: Pedestrian signal indication/instructional sign

Explanation:

Pedestrian signals can be confusing, particularly at crowded urban intersections

with multiple signalheads. It has been well documented that many pedestrians

do not understand the meaning of pedestrian signals and indications, particularly

the flashing DON'T WALK signal.

A pedestrian push button is a device that send a call for the pedestrian phase

of the signal to occur. Pedestrian push-buttons are appropriate where occasional

pedestrian movements occur and adequate opportunities do not exist for pedestrians

to cross. Push-buttons may also be used with pedestrian signals to more quickly

provide a WALK interval and extend the WALK time for pedestrian crossing.

Where no pedestrian signals are present, actuation of the push-buttons may

be used to extend the green phase to allow pedestrians sufficient crossing

time.

It is important to remember that, in order for a person who is blind to know

that the signal has been changed and it is permissible to cross, they must

have cues. Cues are provided by the sound of moving traffic and also by accessible

pedestrian signals. Keep in mind that the use of multi-phased signals makes

it increasingly difficult for pedestrians that are blind to detect when it

is time to cross. More and more cities across the U.S. are installing accessible

pedestrian signals.

The push button should be in an accessible location and height for a person

in a wheelchair, and should be designed so that it can be easily pushed.

Instructional face plates should include Braille lettering and/or other raised

markings.

- Photo Slide: People waiting out in the middle of the road

Explanation:

Pedestrians often need to get to the other side of the street, and there isn't

always a convenient intersection nearby. People on foot do not like to take

detours – they will almost always take the most direct route, even if it means

crossing in a dangerous location.

- Photo Slide: Aerial view mid-block crossing

Explanation:

This is a good example of a location where a midblock crossing was needed.

Without a midblock crossing at this location, a pedestrian would have to walk

an extra half mile to get to the other side of the road. In locations like

this, the best approach is to make the crossing as visible as possible so

that motorists know they may encounter pedestrian crossings. At the crossing

location a pedestrian crossing sign (W11-2) is required and if the crossing

location is not marked with a crosswalk, the crossing sign shall be supplemented

with a diagonal pointing arrow plaque (W16-7P). It is also a good idea to

use an appropriate advance warning sign such as the Pedestrian Warning Sign

(W11-2) with supplemental plaques with the legend "AHEAD" or text

indicating distance to the crosswalk to provide advance notice to drivers.

- Photo Slide: Aerial shot of intersection

Explanation:

ADAAG includes comprehensive guidelines on installing curb ramps at intersections.

These requirements cover both the placement of the ramps at the curb and their

relationship to crosswalk markings in the intersection. Perpendicular curb

ramps (i.e. two per corner, each leading into their own respective crosswalks,

like the ones shown in this photograph) are preferred over diagonal curb ramps.

Diagonal curb ramps direct pedestrians toward the center of the intersection,

and often do not actually connect to the crosswalks.

- Photo Slide: Wheelchair on driveway ramp

Explanation:

The Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) includes

requirements for driveway design. Disabled pedestrians – particularly those

in wheelchairs – have a very difficult time negotiating cross slopes that

are greater than 2%. Steeper cross slopes can cause a wheelchair to tip over.

A sidewalk (such as the one in this photo) that crosses a steep driveway can

cause the person in the wheelchair to lose control and veer towards the street.

These requirements can be hard to meet if the sidewalk is immediately adjacent

to the curb. The photo on the right shows a solution - swing the sidewalk

away from the curb so that it meets the driveway at a level area.

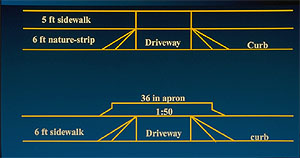

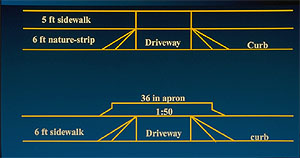

- PowerPoint Graphic Slide: Driveway Design

Explanation:

Accessible driveway design requires that the sidewalk cross the driveway at

a level area, with a cross slope that is no steeper than 1:50 or 2%. This

is easier to do when the sidewalk and roadway are separated by a planting

strip.

- PowerPoint Word Slide (title): Traffic Calming

Explanation:

Traffic calming is a term used to describe ways of encouraging slower speeds

and reducing cut-through traffic through physical modifications to the street

environment.

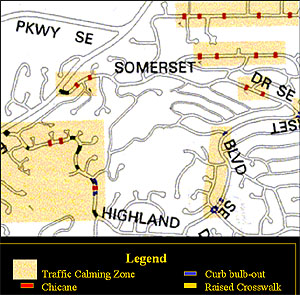

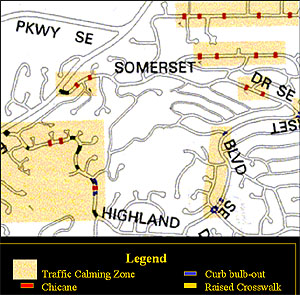

- PowerPoint Graphic Slide: A Traffic Calmed Neighborhood

Explanation:

One important thing to remember about traffic calming is that it is more successful

if it is part of an integrated network of solutions. To be successful, it

requires a comprehensive approach to traffic problems in an area. One speed

hump used as a lone traffic calming device cannot be expected to solve speeding

problems. The best approach is to use a combination of devices.

- Photo Slide: Long, straight, wide street

Explanation:

One of the main goals of traffic calming is to improve the "feel"

of the street, making it more comfortable for pedestrians, and less comfortable

for speeding motorists. A central principal of traffic calming is to visually

narrow the street and eliminate long vistas so that motorists are encouraged

to slow down. Wide, straight streets like the one on the left encourage higher

speeds.

One relatively simple traffic calming method is to "narrow" the

street. In the solution on the right, the pavement markings and a median

are used to visually narrow the street. In this example, they were able to

narrow the lanes to 11' wide, and provide 5' wide bike lanes on both sides.

The median in the center helps to slow down traffic, and also provides a refuge

area for pedestrians (this is not the best example of this since there is

no place on this landscaped median for pedestrians to stand).

A more effective means of slowing motor vehicle traffic is by causing a lateral

or vertical shift in the vehicle path as shown in the following slides:

- Photo Slide: 12' Speed hump

Explanation:

Speed humps are elongated speed bumps. Speed humps have a parabolic cross

section, while speed tables have a flat top. Humps and tables normally have

a height of no more than 3 to 3 1/2 inches and a travel length of 12' or 22'.

A 12' long hump (like the ones shown on the left) can be crossed at 12 mph

A 22' long hump or table (shown on the right) can be crossed at 25 mph (both

cause discomfort at higher speeds). A variety of signing and pavement marking

patterns can be used to warn motorists of the hump.

- Photo Slide: Traffic calming at a pedestrian crossing

As mentioned earlier, the best approach is to combine several methods... This

is a speed table combined with a median to create a "pinch point".

The landscaping in the median also helps to break up the long view down the

street. One challenge in designing this type of device is to make sure that

the landscaping does not create a sight distance problem between motorists

and pedestrians.

- Photo Slide: Traffic circle on a neighborhood

Explanation:

Traffic circles can be used as traffic calming devices at intersections, reducing

vehicle speeds. Mini traffic circles (like the one shown in this photograph)

are raised circular islands constructed in the center of residential street

intersections. They reduce vehicle speeds by forcing motorists to maneuver

around them and are sometimes used instead of stop signs. Traffic circulates

counterclockwise but larger vehicles may have to turn left in front of a circle

in order to successfully maneuver through the intersection. This design works

best when located on residential roads that need traffic calming, but are

not slated for truck use.

- Photo Slide: Roundabout on an arterial street.

Explanation:

Roundabouts are different from traffic circles or rotaries. Modern roundabouts

follow very specific design guidelines that make them safe and efficient.

They have splitter islands on the approaches, and vehicles that are entering

the roundabout are required to yield to traffic in the circle. They have

a raised circle in the center that usually includes landscaping and occasionally

a truck apron to protect it from damage by large trucks. There is no parking

on the approaches to a modern roundabout.

Several studies in the U.S., Europe and Australia have found that roundabouts,

particularly single-lane roundabouts, have better overall safety performance

than stop controlled intersections and signalized intersections. In the U.S.,

a recent study showed that for 24 intersections converted to modern roundabouts

vehicular injury crashes decreased by 76%. Pedestrian crashes at these roundabouts

also decreased, however the numbers were too small to be statistically significant.

A Dutch study of 181 roundabouts (generally single-lane roundabouts) found

a reduction of 89% in pedestrian injuries and a reduction of 30% in bicyclist

injuries after conversion.

These safety improvements are primarily the result of a reduction in the number

of potential conflicts (such as right-angle conflicts and left-turn conflicts)

and slower vehicle speeds. At roundabouts, splitter islands separate entering

and exiting traffic at the approaches and serve as pedestrian refuge islands.

This means that pedestrians need only cross one direction of traffic at a

time.

There are some issues that can make roundabouts challenging for pedestrians.

Often times, the driver's attention is on the roundabout ahead, rather than

the pedestrian crossing in advance of the roundabout. Since traffic is not

required to come to a full stop while entering the roundabout, pedestrian

crossings at roundabouts can be difficult. It should be noted however, that

motor vehicles are required to yield to pedestrians in the crosswalks.

For pedestrians who are blind or vision impaired, roundabouts may be a confusing

and dangerous place. Pedestrians that are blind are very dependent on the

sounds of starting and stopping traffic when negotiating through an intersection.

With a roundabout, however, traffic does not necessarily stop at the intersection,

so it may be difficult for them to know when they are able to cross, difficult

to tell where traffic is coming from, and to know where there are gaps in

the traffic flow.

More research is needed to better understand the perceptions of pedestrians

that are blind or vision impaired and to make roundabouts more comfortable

for these users. Some possible improvements include the addition of sound

cues such as small rumble strips that would alert a user of an approaching

vehicle, pedestrian-activated signals, and a universal crossing-protocol where

pedestrians would raise their hand or walking cane to further alert drivers

of their crossing. Finally, roundabouts with multi-lane entries should only

be built when needed from a capacity standpoint since multi-lane roundabouts

lose some of the safety benefits of single-lane roundabouts.

Reference: FHWA-RD-00-067: Roundabouts: An Informational Guide, Insurance

Institute for Highway Safety, Status Report Vol. 35, No. 5, May 13, 2000

- PowerPoint Word Slide (title): Shared Use Path Design

(also termed Multi-Use Trails and Bike Paths)

Reference for this part of slideshow: AASHTO Guide for the Development

of Bicycle Facilities

- Photo Slide: Baltimore and Annapolis Trail

Explanation:

Multi-use trails are popular among bicyclists and pedestrians for both recreation

and transportation use. These are some great examples of trails in urban

areas that are used for transportation:

- Burke-Gilman Trail, Seattle, Wash.

- Baltimore and Annapolis Trail, MD

- Schuylkill River Greenway, Philadelphia, PA

- Rock Creek Park, Washington, DC

- University Parks Trail, Toledo, Ohio

(and many more)

- Graphic Slide: Cross section of a shared use path

Explanation:

Shared use path design is covered extensively by the AASHTO Guide for the

Development of Bicycle Facilities. The standards cover everything from

horizontal and vertical curvature to trail/roadway intersections to trail

bridge structures. A few basics: paths should be a minimum of 10' wide to

accommodate two-way bicycle travel (some urban areas are installing 12' and

14' wide trails due to heavy use). Shared use paths should have a 2' minimum

level shoulder (with no vertical obstructions).

- Photo Slide: Crowded shared use path with painted lane lines

Explanation:

Shared use paths have become so popular in urban areas that they are often

crowded, leading to conflicts (and sometimes injuries). One solution is to

develop separate lanes of travel, as shown in this photograph.

- Photo Slide: Path user-actuated signal

Explanation:

Shared use path/roadway intersections should be carefully designed to increase

the safety of trail uses. Often, these intersections occur at midblock locations,

where motorists are not expecting pedestrians and bicyclists to cross.

This is a shared use path/roadway intersection on the West Orange Trail near

Orlando, FL. The light stays green until a trail user hits the signal button.

Decisions about whether this type of signal is warranted are usually made

after an engineering analysis that considers anticipated trail volumes, available

"gap" time for pedestrians to cross, and other factors such as visibility

and traffic speed. Warning signingand crosswalk markings are important features

of the crossing as well.

- Photo Slide: Trail bridge

Explanation:

Return to top

Page last modified on February 1, 2013