U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

In This Issue

Safety Compass Newsletter

A publication of the Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration The Safety Compass newsletter is published for internet distribution quarterly by the:

FHWA Office of Safety

1200 New Jersey Avenue SE, Room E71

Washington, DC 20590

The Safety Compass can also be viewed at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov

Editor-in Chief

Janet Ewing

janet.ewing@dot.gov/newsletter/ safetycompass/

Associate Editors

Lincoln Cobb

lincoln.cobb@dot.gov

Judith Johnson

judith.johnson@dot.gov

Your comments and highway safety related articles are welcomed. This newsletter is intended to be a source to increase highway safety awareness, information and provide resources to help save lives. You are encouraged to submit highway safety articles that might be of value to the highway safety community. Send your comments, questions and articles for review (electronically) to: janet.ewing@dot.gov.

Please review guidelines for article submittals at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/newsletter/ safetycompass/guidelines.cfm

If you would like to be included on the distribution list to receive your free issues, please send your email address to: janet.ewing@dot.gov.

They had been on the road since seven that morning, trying to get back home before midnight after a family reunion weekend. It was now 10:30 pm…another hour to go. The kids had fallen asleep hours ago, and his “copilot” in the front seat had dozed off as well. The road was long and empty. Suddenly, a loud buzzing woke everyone in the car…including the driver.

We may never know which drivers have been awakened by a rumblestrip, or which have been saved from a head-on collision by cablebarriers in the median. But the fact is that lives have been saved, and as these improvements are made in more and more States, that impact simply increases.

In this issue of the Safety Compass you will read about these and other life-saving countermeasures that are being put in place across the country. These are readily available technologies and practices that have already been “proven” to address critical safety issues such as roadway departures, intersection crashes and pedestrian fatalities. Many, such as rumble strips, are relatively inexpensive and can be placed on existing roadways or as part of resurfacing projects. Others, such as roundabouts, may have a higher initial cost, but significantly reduce the likelihood of fatal crashes.

In this issue of the Safety Compass you will read about these and other life-saving countermeasures that are being put in place across the country. These are readily available technologies and practices that have already been “proven” to address critical safety issues such as roadway departures, intersection crashes and pedestrian fatalities. Many, such as rumble strips, are relatively inexpensive and can be placed on existing roadways or as part of resurfacing projects. Others, such as roundabouts, may have a higher initial cost, but significantly reduce the likelihood of fatal crashes.

Last year, FHWA identified nine of these “safety countermeasures” and strongly encouraged State and local agencies to try them. We have already found that a number of States have made them a standard practice, while others have invested in statewide applications. While we recognize that not all of these nine countermeasures may apply in every State, we hope that they will at least become part of the base palate of safety solutions used on our Nation's roadways.

The family car pulled into the driveway just before midnight. Everyone was tired, but everyone made it home safely.

Federal Highway Administration Federal Highway AdministrationNine Proven Crash Countermeasures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Countermeasure | Description | Cost Range | Data, Benefits, and Additional Information |

| Road Safety Audits | Road Safety Audit (RSA) is a safety performance examination of an existing or future road or intersection by an independent, multidisciplinary team. |

Very low cost:

Costs are in the form of time |

Crash reduction percentages from 20-80% have been recorded on past projects where a RSA was done. Lifecycle costs are reduced since safer designs often carry lower maintenance costs. Societal costs of collisions are reduced by safer roads and fewer severe crashes. More information at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/ |

| Rumble Strips and Rumble Stripes | Rumble strips are ground into the pavement and are outside of the travel lane. Rumble stripes are ground into the pavement and painted over with the appropriate striping. | Low cost:

Cost will vary based on the application. Prices range between $0.20 and $3.00 per linear foot |

Over 50% of fatal crashes are a result of road departure. This application provides an audible warning and physical vibration to alert drivers they are leaving the roadway. The application of rumble stripes or strips has shown good results in reducing run off the road (ROR) crashes.

More information at: |

| Median Barriers | Median Barriers separate opposing traffic on a divided highway and are used to redirect vehicles striking either side of the barrier. | Medium to high cost:

Cost will vary depending on the material used. Cable barrier systems can be installed on average for $76,500 per mile. |

Cross-median crashes can be some of the most severe and most result in a serious injury or death. Median Barriers can significantly reduce the occurrence of cross-median crashes and the overall severity of median-related crashes.

More information at: |

| Safety Edge | Safety Edge is a paving technique where the interface between the roadway and graded shoulder is paved at an angle to eliminate vertical drop-off. | Very low cost:

The technique requires a slight change in the paving equipment (approximately $1,200). |

Research between 2002-2004 shows that pavement edges may have been a contributing factor in as many as 15-20% of ROR crashes. When a driver drifts off the roadway and tries to steer back onto the pavement the action may result in over-steering. Safety Edge minimizes that occurrence by reducing the vertical angle between the shoulder and pavement.

More information at: |

| Roundabouts | Roundabouts are circular intersections with specific design and traffic control features that ensure low travel speeds (<30mph) through the circulatory roadway. | High cost:

Installations may require additional R.O.W.. A reduction in serious crashes may justify the costs. |

Roundabouts offer substantial safety advantages and can reduce the occurrence of right angle crashes and have the potential to reduce fatal and injury crashes from 60–87%. Geometric features provide a reduced speed environment and excellent operational performance.

More information at: |

| Left and Right Turn Lanes | Installation of turn lanes reduces crash potential, motorist inconvenience, and improves operational efficiency. | Medium to high costs:

Some installations may require additional R.O.W. |

Rear-end crashes are the most frequent type of collisions at intersections. Adding turn lanes provides separation between turning and through traffic and reduces these types of conflicts. It is desirable to offset opposing left turn lanes to increase visibility of approaching vehicles.

More information at: |

| Yellow Change Intervals | Yellow Change Intervals should be appropriate for the speed and distance traveled at a signalized intersection. | Very low cost:

Time and interagency coordination are required. |

Yellow Change Intervals that are not consistent with normal operating speeds create a dilemma zone in which drivers can neither stop safely nor reach the intersection before the signal turns red. Increasing yellow time to meet the needs of traffic can dramatically reduce red light running.

More information at: |

| Median and Pedestrian Refuge Areas | Median and Pedestrian Refuge Areas provide additional protection for pedestrians and lessen their risk of exposure to oncoming traffic. | Low cost:

Retrofit improvement, lower costs for new roadway projects. |

Pedestrian fatalities account for approximately 12% of all highway fatalities. Providing raised medians or pedestrian refuge areas has demonstrated a 46% reduction in pedestrian crashes. Raised medians or refuge areas are especially important at multi-lane intersections with high volumes of traffic.

More information at: |

| Walkways | Pathways, sidewalks, or paved shoulders should be provided wherever possible, especially in urban areas and near school zones where there are high volumes of bikes and pedestrians. | Medium to high cost:

Based on the amount and type of application. |

“Walking along road” pedestrian crashes are approximately 7.5% of all pedestrian crashes. The presence of a path, sidewalk or paved shoulder can provide a significant reduction in “walking along road” pedestrian crashes.

More information at: |

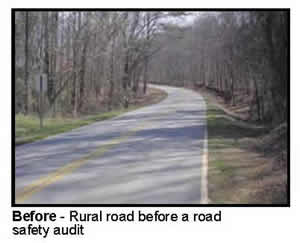

A Road Safety Audit (RSA) is a very effective tool to reduce injuries and fatalities on our Nation's roadways. It qualitatively estimates and reports on potential road safety issues and identifies opportunities for improvements in safety for all road users. The aim of an RSA is to answer the following two questions: What elements of the road may present a safety concern and, to what extent, to which road users, and under what circumstances? What opportunities exist to eliminate or mitigate identified safety concerns?

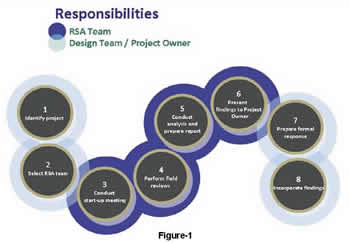

An RSA is the formal safety performance examination of an existing or future road or intersection by an independent, multidisciplinary team. The use of the words “formal,” “multidisciplinary” and “independent” is very important in terms of defining an RSA and setting it apart from a typical safety review. An RSA is formal in that it provides written documentation of the process, the team recommendations developed for the site is provided to the facility owner for response. An RSA includes a multidisciplinary team, which may include safety, operations, maintenance and law enforcement officials who provide their unique perspectives to a safety concern. Finally, RSAs are independent in that they are performed by a team that is not directly related to the design of the project. Typically, an RSA involves eight basic steps (see Figure-1 below):

An RSA is the formal safety performance examination of an existing or future road or intersection by an independent, multidisciplinary team. The use of the words “formal,” “multidisciplinary” and “independent” is very important in terms of defining an RSA and setting it apart from a typical safety review. An RSA is formal in that it provides written documentation of the process, the team recommendations developed for the site is provided to the facility owner for response. An RSA includes a multidisciplinary team, which may include safety, operations, maintenance and law enforcement officials who provide their unique perspectives to a safety concern. Finally, RSAs are independent in that they are performed by a team that is not directly related to the design of the project. Typically, an RSA involves eight basic steps (see Figure-1 below):

Public agencies with a desire to improve the overall safety performance of roadways should be excited about the concept of RSAs. An RSA can be used in any phase of project development, from planning and preliminary engineering, through design and construction, on any size project, from minor intersections and roadway retrofits to mega-projects. See FHWA RSAGuidelines (FHWA-SA-06-06).

Many States are using RSAs as a process for conducting engineering studies, as listed in 23 CFR Section 924.9 of the Highway Safety Improvement Program, while other States fund the audit/assessment recommendations through their HSIP. Many States have incorporated RSAs into their safety management program and Strategic Highway Safety Plans (SHSPs).

The use of RSAs is increasing across the United States, in part due to crash reductions of up to 60 percent in locations where they have been applied. The South Carolina DOT RSA program has had a positive impact on safety. Early results from four separate RSAs, following 1-year of results, are promising. One site, implementing 4 of the 8 suggested improvements, saw total crashes decrease 12.5 percent, resulting in an economic savings of $40,000. A second site had a 15.8 percent decrease in crashes after only 2 of the 13 suggestions for improvements were incorporated. A third site, implementing all 9 suggested improvements, saw a 60 percent reduction in fatalities, resulting in an economic savings of $3.66 million dollars. Finally, a fourth location, implementing 25 of the 37 suggested safety improvements, had a 23.4 percent reduction in crashes, resulting in an economic savings of $147,000.

| Most State DOTs have established traditional safety review processes. However, a road safety audit and a traditional safety review are different processes. The main differences between the two are shown below: | |

| Road Safety Audit | Traditional Safety Review |

|---|---|

| Performed by a team independent of the project | The safety review team is usually not completely independent of the design team |

| Performed by a multi-disciplinary team | Typically performed by a team with only design and/or safety expertise |

| Considers all potential road users | Often concentrates on motorized traffic |

| Accounting for road user capabilities and limitations is an essential element of an RSA | Safety Reviews do not normally consider human factor issues |

| Always generates a formal RSA report | Often does not generate a formal report |

| A formal response report is an essential element of an RSA | Often does not generate a formal response report |

The major quantifiable benefits of RSAs can be identified in the following areas:

Societal costs of collisions are reduced by safer roads and fewer, less-severe crashes.

Liability claims, a component of both agency and societal costs, are reduced.

Lifecycle costs are reduced since safer designs often carry lower maintenance costs (e.g., flattened slope versus guardrail).

The State of Nevada experienced a 14 percent drop in fatalities, from 432 to 372, in 2007. This appears to be the result of multiple safety improvement initiatives, including RSAs. RSAs are standard practice at the Nevada DOT, which considers RSAs a programmatic approach to safety.

Section 625.2 of 23 CFR states that plans and specifications for proposed NHS projects “shall adequately serve the existing and planned future traffic of the highway in a manner that is conducive to safety, durability, and economy of maintenance.” While numerous requirements and analytical methods have been developed to support Federal-Aid project decision-making, few requirements or analytical tools have been applied that relate to safety. The use of RSAs for this purpose would result in significant reductions in the numbers of fatalities and injuries.

To ensure RSAs are a part of your safety management system, consider the development of an RSA policy. The policy should identify which projects will have RSAs conducted and when (at what project stage). Consideration of types of projects, project cost thresholds and the likelihood of producing significant, beneficial safety recommendations for implementation should be included. The policy should cover who will conduct the RSA and how it will be funded. The policy may list the project types or categories considered to have the highest potential benefit from application of an RSA. An RSA policy should contain procedures for prompt reviews of RSA recommendations, and procedures for implementing accepted RSA recommendations.

There are two practical methods for starting an RSA program: (a) participation in RSA training and (b) use of the RSA Peer to Peer program. The National Highway Institute, the training arm of the FHWA, offers a course on RSAs. This course includes “hands-on” application of the training materials, including topics such as: RSA definition and history, stages and how to conduct an RSA, and legal considerations. The course number is 380069.

In order to provide assistance to agencies considering the use of or actually conducting RSAs, FHWA has established an RSA Peer-to-Peer (P2P) program. The RSA P2P program is provided at no cost to State, local and tribal transportation agencies, and it's easy to access the support of a knowledgeable peer.

Assistance can be requested by email SafetyP2P@fhwa.dot.gov or by calling the toll-free number (866) P2P-FHWA.

“We view the RSAs as a proactive, low-cost approach to improve safety. The RSAs helped our engineering team develop a number of solutions, incorporating measures that were not originally included in the projects. The very fi rst audit conducted saved SCDOT thousands of dollars by correcting a design problem.”

Terecia Wilson - Director of Safety

South Carolina Department of Transportation

“The road safety audit process looks at the roadway from a purely technical safety viewpoint without outside infl uences. It is a valuable process that gives an unbiased view of safety issues with support from safety experts. These recommendations are helpful when working with others, such as political leaders.”

Ricky May - District Engineer

Mississippi DOT

FHWA RSA Newsletter (Quarterly): http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/newsletter/

FHWA Road Safety Audit Guidelines, February 2005, http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/guidelines/

FHWA Road Safety Audit Webpage: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/

FHWA Priority Technologies and Innovations 2008 List: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/crt/lifecycle/ptisafety.cfm

FHWA SA-07-007, Pedestrian Road Safety Audit Guidelines and Prompt Lists, FHWA SA-07-007, 2007. http://drusilla.hsrc.unc.edu/cms/downloads/PedRSA.reduced.pdf

FHWA RSA Software: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/software/FHWA RSA Peer to Peer (P2P) program: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/resources/p2p_brochure.cfm

Office of Safety:

Becky Crowe

rebecca.crowe@dot.gov

(202) 507-3699

FHWA Resource Center:

Craig Allred

craig.allred@dot.gov

(720) 963-3236

Rumble strips are raised or grooved patterns on the roadway that provide both an audible warning (rumbling sound) and a physical vibration to alert drivers that they are leaving the driving lane. They may be installed on the roadway shoulder or on the centerline of undivided highways. If the placement of rumble strips coincides with centerline or edgeline striping, the devices are referred to as rumble stripes.

The 2005 NCHRP Synthesis 339 (data from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety study on centerline rumble strips in September 2003) found that head-on and opposite direction sideswipe injury crashes were reduced by an estimated 25 percent at sites treated with centerline rumble strips or stripes. Centerline rumble strips/stripes have been shown to provide a crash reduction factor of 14 percent of all crashes and 15 percent of injury crashes on rural two-lane roads.

The 2005 NCHRP Synthesis 339 (data from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety study on centerline rumble strips in September 2003) found that head-on and opposite direction sideswipe injury crashes were reduced by an estimated 25 percent at sites treated with centerline rumble strips or stripes. Centerline rumble strips/stripes have been shown to provide a crash reduction factor of 14 percent of all crashes and 15 percent of injury crashes on rural two-lane roads.

Continuous shoulder rumble strips (CSRS) can be applied on many miles of rural roads in a cost-effective manner. Studies have documented the following crash reduction benefits:

Edge line rumble stripes have not been studied to the same extent as centerline or shoulder strips. However, they show great potential for reducing run-off-the-road crashes in addition to improving night-time visibility.

Encourage your own agency or your State partners to install rumble strips or rumble stripes on all new rural freeways and on all new rural two-lane highways with travel speeds of 50 mph or greater. In addition, State 3R and 4R policies should consider:

Installation of centerline rumble strips (or stripes) on rural two-lane road projects where the lane plus shoulder width beyond the rumble strip will be at least 13' wide; particularly roadways with higher traffic volumes, poor geometrics, or a history of head-on and opposite-direction sideswipe crashes.

Installation of continuous shoulder rumble strips on all rural freeways and on all rural two-lane highways with travel speeds of 50 mph or above (or as agreed to by the Division and the State) and/or a history of roadway departure crashes, where the remaining shoulder width beyond the rumble strip will be 4 feet or greater.

Federal and local agencies and tribal governments administering highway projects using Federal funds should also be encouraged to adopt similar policies for providing rumble strips or stripes.

NCHRP Project 17-32, Guidance for the Design and Application of Shoulder and Centerline Rumble Strips (projected release date of August 2009) http://www.trb.org/trbnet/projectdisplay.asp?projectid=458

Technical Advisory 5040.35, Roadway Shoulder Rumble Strips https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/legsregs/directives/techadvs/t504035.htm

NCHRP Synthesis 339, Centerline Rumble Strips http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/nchrpnchrp_syn_339.pdf

Office of Safety:

Cathy Satterfield

cathy.satterfield@dot.gov

(708) 283-3552

FHWA Resource Center:

Frank Julian

frank.julian@dot.gov

(404) 562-3689

Q&A - Rumble Strips and Rumble Stripes

Q: Does the guidance recommend shoulder rumble strips only where a clear 4-foot surface is provided beyond the rumble strip?

A: No. The guidance recommends that shoulder rumble strips be installed on all roadways meeting certain criteria regarding speed, crash history, etc. The presence of a 4-foot shoulder is one of the listed criteria. So while the guidance recommends shoulder rumble strips where there is 4 feet or greater of shoulder beyond the strips, it does not recommend against rumbles where there is less than 4 feet. In those cases there are many issues for the responsible agency to consider, including whether the shoulder is used by bicyclists and therefore needs a specified amount of paved area beyond the rumble strip to accommodate them. Using the metric of 4-feet in the recommendation allows a practice that will work as a typical application, and accommodate cyclists. Use of shoulder rumble stripes can also maximize the width of shoulder available to bicyclists.

Q: For new highways, is the recommendation to place both shoulder and centerline rumble strips?

A: As applicable, yes. For example, on a two-lane road that has adequate space for both centerline and shoulder rumble strips within the policy parameters, we would recommend the use of both. Freeways on the other hand, do not have centerlines, but it is recommended that the shoulder rumble strips be placed on both the right shoulder and the left (or median side) shoulder.

Q: Are rumble strips recommended for residential use?

A: Not typically. Noise is often an issue in residential areas, so other alternatives may be more appropriate. However, sometimes rumbles strips or rumble stripes are appropriate along highways with light residential land use in rural areas or on the urban or suburban fringe.

Q: Why does the guidance not recommend rumble strips on multi-lane highways other than rural freeways?

A: Rural conditions are where rumble strips can be most effective and there are few obstacles to their installation. It is not our intent to limit the use of rumble strips in non-rural applications, however, there is not enough information currently available to address those at a policy level. The policy should be applied to all rural multi-lane highways, not just freeways.

Q: The Technical Advisory suggests rumble strips should be at least 12 inches wide. Is this still the recommended minimum width?

A: Not necessarily. A few agencies have installed 6-inch rumble stripes where they have no paved shoulder. While they have shown diminished results, there are safety benefits. Since these are new, it is recommended that an evaluation be completed on each installation.

Q: Are rumble stripes (centerlines or edge lines placed within the rumble strip) allowed? They do not appear to meet the guidelines provided in the Technical Advisory.

A: Rumble stripes are encouraged where appropriate because the added benefit of providing additional

delineation beyond a flat marking. The technical advisory only addresses should rumble strips and will be updated in the near future after NCHRP Project 17-32 is published.

Median barriers are longitudinal barriers used to separate opposing traffic on a divided highway. They are designed to redirect vehicles striking either side of the barrier.

Median barriers can significantly reduce the occurrence of cross-median crashes and the overall severity of median-related crashes.

Crashes resulting from errant vehicles crossing the median and colliding with traffic on the opposing roadway often result in severe injuries and fatalities. The fact that these crashes involve innocent motorists is another compelling reason for highway agencies to take action.

In the past, median barriers were not typically used with medians that were more than 30 feet wide. In the 1980's and 1990's, however, a number of States experienced a large number of cross median fatal crashes. This led them to review their design policies and begin installing barriers in medians wider than the 30 feet originally called for in the AASHTO Roadside Design Guide (RDG). The 2006 RDG revision encourages consideration of barriers in medians up to 50 feet wide.

A recent review of cross median fatality data shows many States experiencing crashes involving vehicles traversing medians well in excess of 30 feet. Although W-beam guardrail has typically been used to prevent medians crossovers, more recently many States have demonstrated that cable median barriers are a very cost-effective means of reducing the severity of median encroachments. Although a small number of high-profile crashes involving vehicles going over or under cable barrier systems has caught the public's attention, the failure rate of cable systems is comparable to, or may even be lower than, that for W-beam median barriers. Cable systems are a highly cost-effective way to impact crossmedian crashes by reducing the number and severity of such crashes, and the FHWA has been actively urging each State to install cable median barrier, where feasible, on highway segments.

Encourage your State to update its median barrier policy to be consistent with the 2006 Roadside Design Guide Chapter 6 revision.

Where median barriers are determined to be needed, your State should be encouraged to give strong consideration to cable median barriers.

AASHTO Roadside Design Guide, 3rd Edition, 2006

https://bookstore.transportation.org/item_details.aspx?ID=148

NCHRP Report 500 “Volume 20: A Guide for Reducing Head-On Crashes on Freeways

http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_500v20.pdf

Office of Safety:

Nick Artimovich

nick.artimovich@dot.gov

(202) 366-1331

FHWA Office of Safety R&D:

Ken Opiela,

kenneth.opiela@dot.gov

(202) 493-3371

FHWA Resource Center:

Frank Julian,

frank.julian@dot.gov

(404) 562-3689

Q: Is there a speed below which cable median barriers are not recommended?

A: Although the guidance is intended to address freeways, there is no minimum speed below which cable median barrier is ineffective.

Q: Is it safe to use cable median barrier where 85 percentile speeds exceed 65 mph?

A: Yes. When updating NCHRP 350, researchers found that barrier impacts typically did not exceed 100 km/hr (62.5 mph), even when the travel speeds were higher. For this reason, crash testing of median barrier continues to be conducted at 100 km/hr.

Q: I s it true that even minor impacts to cable median barrier result in extensive damage to the barrier?

A: High-tension cable barriers are more impact-tolerant than low-tension barriers, and the cables often remain in place if not many posts have been hit. Additional information on typical repairs may be available from the vendors of the specific cable rail systems

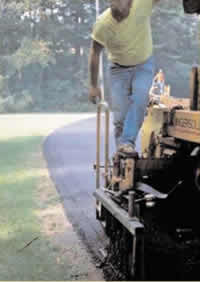

The Safety Edge is a specific asphalt paving technique where the interface between the roadway and graded shoulder is paved at an optimal angle to provide a safer roadway edge. A Safety Edge shape can be readily attained by fitting resurfacing equipment with a device that extrudes the shape of the pavement edge as the paver passes. This mitigates shoulder pavement edge drop-offs immediately during the construction process and over the life of the pavement. This technique is not an extra procedure but merely a slight change in the paving equipment that has a minimal impact on the project cost. In addition, the Safety Edge improves the compaction of the pavement near the edge. Shoulders should still be pulled up fl ush with the top of the pavement at project completion.

New and resurfaced pavements improve ride quality but can be a detriment to safety if the edges are left near vertical. Drivers trying to regain control after inadvertently dropping a tire over the edge frequently have difficulty with a vertical edge and may lose control of the vehicle, possibly resulting in severe crashes. Making the adjacent non-paved surface fl ush with the paved surface alleviates this problem, but a vertical edge may appear due to erosion or wheel encroachment, especially along curves. Installing the Safety Edge during a paving project provides a surface that can be more safely traversed.

Recent studies have shown that crashes involving pavement edge drop-offs greater than 2.5 inches are more severe and twice as likely to be fatal than other roadway departure crashes. An effective countermeasure is to implement a pavement wedge as referenced in the AASHTO Roadside Design Guide, Chapter 9. Research in the early 1980's found a 45 degree pavement wedge effective in mitigating the severity of crashes involving pavement edge drop-offs. During the Georgia DOT Demonstration project, evaluation of wedge paving techniques found it beneficial to flatten the wedge to a 30 to 35 degree angle resulting in a pavement edge referred to as the Safety Edge. Subsequent research has shown this design to be approximately 50 percent more effective than the original 45 degree wedge.

Encourage your State to implement policies and procedures that incorporate the Safety Edge where pavement and non-pavement surfaces interface on all Federal-Aid new paving and resurfacing projects. Regrade adjacent shoulders as usual. The Safety Edge will provide an additional safety factor when the adjacent non-paved surface settles, erodes or is worn down.

Encourage your State to implement policies and procedures that incorporate the Safety Edge where pavement and non-pavement surfaces interface on all Federal-Aid new paving and resurfacing projects. Regrade adjacent shoulders as usual. The Safety Edge will provide an additional safety factor when the adjacent non-paved surface settles, erodes or is worn down.

In addition, Divisions should work with Federal, State and local agencies and tribal governments to determine how the Safety Edge can be installed on all routes with pavement edge drop-offs (i.e., surface differentials of 2.5 inches or greater) during resurfacing over time, based on highest priority by traffic volume, lack of paved shoulders, and historical presence of edge rutting or pavement edge drop-offs.

AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, Safety Impacts of Pavement Edge Drop-offs

http://www.aaafoundation.org/pdf/pedo_report.pdf

The Safety Edge: Pavement Edge Treatment, FHWA-SA-05-003:

http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/roadway_dept/docs/sa05003.htm

Frank Julian,

frank.julian@dot.gov

(404) 562-3689

and

Chris Wagner,

chris.wagner@dot.gov

(404) 562-3693

Crashes involving pavement edge drop-offs greater than 2.5 inches are more severe

Q&A - Safety Edge

Q: Have crash data been studied to evaluate the Safety Edge?

A: Research is now underway, although it will be some time before enough data are available to develop a crash reduction factor. Based on what we know, and the insignificant additional costs of adding this feature to a paving job, we felt comfortable including a recommendation on this countermeasure.

Q: Can a Safety Edge be installed on concrete pavement?

Q: Can a Safety Edge be installed on concrete pavement?

A: Yes, this has been done in Iowa.

Q: My State pulls up gravel shoulders as part of resurfacing projects. Is there still a benefit to using the Safety Edge?

A: Yes. Over time, unpaved shoulders can erode, either through runoff or from vehicles using the shoulder, and research has shown that this can occur within a few months. The Safety Edges provides a “safety net” of sorts until the shoulders can be regraded.

Q: My State utilizes only paved shoulders. Is there any benefit to using the Safety Edge?

A: The primary purpose of the Safety Edge is to mitigate the vertical dropoff which occurs when an unpaved shoulder erodes at its interface with the paved surface. While paving the shoulder eliminates the occurrence of this dropoff, the Safety Edge can still provide a long-term benefit where a vehicle may stray beyond the paved shoulder. The benefit is obviously greater when the paved shoulder is narrow.

Q: Is obtaining compaction on the Safety Edge a concern?

A: The typical paving process does not compact the pavement edge, and often raveling and pavement edge deterioration occurs. The current safety edge shape of 30 to 35 degrees is an important safety characteristic; however, without consolidation, the Safety Edge is also susceptible to deterioration. With an appropriate screed attachment shoe, such as the one developed by Georgia DOT or one that is available commercially, adequate consolidation is attained via extrusion of the material. The high degree of compaction required in the wheel path is not necessary on the edge. Compaction of concrete is, of course, not an issue.

The modern roundabout is a type of circular intersection defined by the basic operational principle of entering traffic yielding to vehicles on the circulatory roadway, combined with certain key design principles to achieve deflection of entering traffic by channelization at the entrance and deflection around a center island. Modern roundabouts have geometric features providing a reduced speed environment that offers substantial safety advantages and excellent operational performance.

Roundabouts have demonstrated substantial safety and operational benefits compared to other forms of intersection control, with reductions in fatal and injury crashes from 60 - 87 percent. The benefits apply to roundabouts in urban and rural areas and freeway interchange ramp terminals under a wide range of traffic conditions. Although the safety of all-way stop control is comparable to roundabouts, roundabouts provide much greater capacity and operational benefits. Roundabouts can be an effective tool for managing speed and transitioning traffic from a high speed to a low speed environment. Proper site selection and channelization for motorists, bicyclists, and pedestrians are essential to making roundabouts accessible to all users. Particularly at higher speed roundabouts, it is important to ensure safe accommodation of bicyclists and pedestrians who have visual or cognitive impairments.

Roundabouts have demonstrated substantial safety and operational benefits compared to other forms of intersection control, with reductions in fatal and injury crashes from 60 - 87 percent. The benefits apply to roundabouts in urban and rural areas and freeway interchange ramp terminals under a wide range of traffic conditions. Although the safety of all-way stop control is comparable to roundabouts, roundabouts provide much greater capacity and operational benefits. Roundabouts can be an effective tool for managing speed and transitioning traffic from a high speed to a low speed environment. Proper site selection and channelization for motorists, bicyclists, and pedestrians are essential to making roundabouts accessible to all users. Particularly at higher speed roundabouts, it is important to ensure safe accommodation of bicyclists and pedestrians who have visual or cognitive impairments.

Roundabouts are the preferred safety alternative for a wide range of intersections. Although they may not be appropriate in all circumstances, they should be considered as an alternative for all proposed new intersections on Federally-funded highway projects, particularly those with major road volumes less than 90 percent of the total entering volume. Roundabouts should also be considered for all existing intersections that have been identified as needing major safety or operational improvements. This would include freeway interchange ramp terminals and rural intersections.

Roundabouts are the preferred safety alternative for a wide range of intersections. Although they may not be appropriate in all circumstances, they should be considered as an alternative for all proposed new intersections on Federally-funded highway projects, particularly those with major road volumes less than 90 percent of the total entering volume. Roundabouts should also be considered for all existing intersections that have been identified as needing major safety or operational improvements. This would include freeway interchange ramp terminals and rural intersections.

Roundabouts: An Informational Guide

(Report No. FHWA-RD-00-067)

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/safety/00068/

Public Rights-of-Way Access Advisory

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/resources/prwaa.cfm

Pedestrian Access to Modern Roundabouts: Design and Operational Issues for Pedestrians who are Blind

http://www.access-board.gov/research/roundabouts/bulletin.htm#CROSSING%20AT%20ROUNDABOUTS

NCHRP Project 03-78A, Crossing Solutions at Roundabouts and Channelized Turn Lanes for Pedestrians with Vision Disabilities

http://www.trb.org/TRBNet/ProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=834

Desktop Reference for Crash Reduction Factors, FHWA-SA-07-015, 2007

http://www.transportation.org/sites/safetymanagement/docs/Desktop%20Reference%20Complete.pdf

NCHRP Report 572: Roundabouts in the United States

http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_572.pdf

Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, 2004.

Office of Safety:

Ed Rice

ed.rice@dot.gov

(202) 366-9064

FHWA Office of Safety R&D:

Joe Bared

joe.bared@dot.gov

(202) 493-3314

FHWA Resource Center:

Mark Doctor

mark.doctor@dot.gov

(404) 562-3732

Q&A - Roundabouts

Q: How do roundabouts accommodate pedestrians and bicyclists?

A: At a roundabout, pedestrians should be accommodated with a sidewalk around the entire perimeter of the intersection, and pedestrians should not cross the traveled way to enter the central island. Most roundabout design guidelines recommend offsetting the pedestrian crossing by one to three car lengths in advance of the roundabout yield line, which not only shortens the crossing distance but allows motorists approaching the roundabout to yield to pedestrians in the crossing before they are at the roundabout merge line. Pedestrians only have to cross one direction of traffic at a time, with the splitter island in the median providing refuge, and traffic approaching a roundabout is moving at relatively slow speeds. Roundabouts have fewer conflict points than traditional intersections, and left turns across opposing traffic are eliminated. For all of these reasons, roundabouts, particularly single-lane ones, offer significant safety advantages for pedestrians over other types of intersections.

Roundabouts offer similar advantages for bicyclists. Roundabouts do not have striped bike lanes within the circulatory roadway. A bicyclist using a roundabout can proceed either as a motor vehicle by “taking a lane” or as a pedestrian by dismounting and using the sidewalk and marked crosswalk, the same as with traditional intersections. The slow vehicle speeds in a roundabout are similar to those that can be attained by experienced bicyclists. Less experienced bicyclists can choose to exit the roadway in advance of the roundabout entry and share the sidewalk with pedestrians. As with traditional intersections with multiple turn lanes, a multi-lane roundabout also becomes more difficult for bicyclists to traverse.

Q: How do roundabouts accommodate visually impaired pedestrians?

A: Since visually-impaired pedestrians rely on audible clues to know when traffic is stopped so they can cross a roadway, roundabouts present a challenge since motorists may not have to stop. Properly designed walkway edges, curb ramps and tactile marking warning devices at the sidewalk sides of the crossing and in the splitter island aligned with the crosswalk can help in detecting where to cross. To assist in identifying when to cross, there are a number of studies underway that are looking at infrastructure-related alternatives such as:

In summary, this is an issue that is receiving a good bit of attention in identifying the best solutions for sight-impaired pedestrians at roundabouts.

Left turn lanes are auxiliary lanes for storage or speed change of left turning vehicles. Installation of left turn lanes reduces crash potential and motorist inconvenience, and improves operational efficiency. Right turn lanes provide a separation between right turning traffic and adjacent through traffic at intersection approaches, reducing conflicts and improving intersection safety.

Background: The AASHTO Green Book recommends that left turning traffic be removed from the through lanes whenever practical, and that left turn lanes should be provided at street intersections along major arterials and collector roads wherever left turns are permitted. Consideration of left turn lanes has traditionally been based on such factors as the number of through lanes, speeds, left turn volumes, opposing through volumes, and/or left turning crashes. Providing left turn lanes on the major road approaches delivers proven safety benefits at rural and urban 3 and 4-leg, two-way stop-controlled intersections. Studies have shown total crash reductions ranging from 28-44 percent and fatal/injury crash reductions of 35-55 percent when a left turn lane was installed on one major road approach, and 48 percent when left turn lanes were installed on both major road approaches, at rural intersections with traffic volumes ranging from 1,600-32,400 vehicles per day (vpd) on the major road and 50-11,800 on the minor road.

For urban intersections, total crash reductions of 27-33 percent and fatal/injury crash reduction of 29 percent have been experienced after providing a left turn lane on one major road approach, and 47 percent for providing left turn lanes on two major road approaches at intersections with traffic volumes from 1,520-40,600 vpd on the major road and 200-8,000 vpd on the minor road.

For urban intersections, total crash reductions of 27-33 percent and fatal/injury crash reduction of 29 percent have been experienced after providing a left turn lane on one major road approach, and 47 percent for providing left turn lanes on two major road approaches at intersections with traffic volumes from 1,520-40,600 vpd on the major road and 200-8,000 vpd on the minor road.

Providing right turn lanes on major road approaches has been shown to reduce total crashes at two-way stopcontrolled intersections by 14 percent and fatal/injury crashes by 23 percent when providing a right turn lane on one major road approach, and a total crash reduction of 26 percent for right turn lanes on both approaches, at 3 and 4-leg urban and rural intersections with traffic volumes ranging from 1,520-40,600 vpd on the major road and from 25-26,000 vpd on the minor road.

Encourage your State to consider installing left turn lanes and right turn lanes on major road approaches for improving safety at 3 and 4-leg intersections with two-way stop control on the minor road, where significant turning volumes exist or where there is a history of turnrelated crashes. Safe accommodation of pedestrians and bicyclists at these intersections should be considered as well.

Desktop Reference for Crash Reduction Factors, FHWA, SA-07-015, 2007

http://www.transportation.org/sites/safetymanagement/docs/Desktop%20Reference%20Complete.pdf

NCHRP Project 17-27, Highway Safety Manual, Parts I and I1

| NCHRP Report 500, Volume 5, A Guide for Addressing Unsignalized Intersection Collisions http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_500v5.pdf Safety Effectiveness of Intersection Left and Right Turn Lanes (FHWA-RD-02-089) NCHRP Project 03-91, Left Turn Accommodations at Unsignalized Intersections (underway) Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. 2004. FHWA ContactsOffice of Safety: FHWA Office of Safety R&D: FHWA Resource Center: |

|

Q&A - Left and Right Turn Lanes at Stop-Controlled Intersections Q: Does offsetting of turn lanes provide an additional safety benefit? A: Yes. Research has generally shown that providing offset left turn lanes, compared to left turn lanes which are not offset, provides an additional safety benefit, particularly where there is a left turn crash problem at an existing intersection with a non-offset left turn lane and there are sight obstructions caused by opposing left turn vehicles. Although research on offset right turn lanes has not been as extensive, the safety principals are the same and therefore a benefit can be expected for offsetting right turn lanes, also. Q: Are there situations where turn lanes are not recommended, such as when they may create temporary sight obstructions? A: There may circumstances where a left turn lane may not be recommended at an unsignalized intersection due to horizontal and/or vertical sight restrictions. Horizontal sight obstructions may be able to be cost-effectively alleviated with an offset left turn lane if sufficient width exists and additional right-of-way is not required. Vertical sight restrictions would be more difficult to account for, and may lead to prohibiting left turns at the intersection and providing for them via u-turns downstream or via a jughandle confi guration. |

The yellow change interval following a green signal is displayed to warn drivers of the impending change in right of way assignment. Yellow change intervals that are not consistent with normal operating speeds create a dilemma zone in which drivers can neither stop safely nor reach the intersection before the signal turns red.

|

Increasing yellow time to meet the needs of traffic can dramatically reduce red light running |

Red-light running is one of the most common causes of intersection crashes. Research shows that yellow interval duration is a significant factor affecting the frequency of red-light running and that increasing yellow time to meet the needs of traffic can dramatically reduce red light running. Bonneson and Son (2003) and Zador et al.(1985) found that longer yellow interval durations consistent with the ITE Proposed Recommended Practice (1985) using 85th percentile approach speeds are associated with fewer red-light violations, all other factors being equal. Bonneson and Zimmerman (2004) found that increasing yellow time in accordance with the ITE Proposed Recommended Practice or longer reduced red light violations more than 50 percent. Van Der Host found that red light violations were reduced by 50 percent one year after yellow intervals were increased by 1 second. Retting et al, (2007) found increasing yellow time in accordance with the ITE Proposed Recommended Practice reduced red-light violations on average 36 percent. Retting, Chapline & Williams (2002) found that adjusting the yellow change interval in accordance with the ITE Proposed Recommended Practice reduced total crashes by 8 percent, reduced right angle crashes by 4 percent, and pedestrian and bicycle crashes by 37 percent. Both Kentucky and Missouri report a 15 percent reduction in all crashes and a 30 percent reduction in right-angle crashes after increasing the yellow interval.

Encourage your State to increase the length of the yellow change interval at any intersection where the existing yellow change interval time is less than the time needed for a motorist traveling at the prevailing speed of traffic to reach the intersection and stop comfortably before the signal turns red. The minimum length of yellow should be determined using the kinematics formula in the 1985 ITE Proposed Recommended Practice assuming an average deceleration of 10 ft/sec2 or less, a reaction time of typically 1 sec, and an 85th percentile approach speed. An additional 0.5 sec of yellow time should be considered for locations with significant truck traffic, significant population of older drivers, or where more than 3 percent of the traffic is entering on red.

Desktop Reference for Crash Reduction Factors, FHWA-SA-07-015, 2007

http://www.transportation.org/sites/safetymanagement/docs/Desktop%20Reference%20Complete.pdf

Office of Safety:

Edward Sheldahl

edward.sheldahl@dot.gov

(202) 366-2193

FHWA Office of Safety R&D:

Joe Bared

joe.bared@fhwa.dot.gov

(202) 493-3314

FHWA Resource Center:

Fred Ranck

fred.ranck@fhwa.dot.gov

(708) 283-3545

Q&A - Yellow Change Intervals Q: Is the guidance inconsistent with the current ITE standard practice (particularly the “should” conditions regarding extra time for truck traffic, older drivers, and red-light entries)? A: In 1985 ITE published “Determining Vehicle Change Intervals: The ITE proposed recommended practice is the recognized level of practice throughout the USA. The FHWA guidance included in the memo provides further information that should be considered by those applying the ITE recommended practice. In 2008, ITE formed a technical advisory committee to help develop a Recommended ITE Practice for Change Intervals, based on a current NCHRP project. This should be finalized by 2010 or 2011, and would logically result in an ITE Recommended Practice. If this resulted recommended practice differs from the guidance, we will revise the guidance accordingly. Q: Is there a maximum on the amount of yellow time that should be provided? A: The yellow clearance interval should not exceed six seconds. This is consistent with existing MUTCD guidance. |

|

The median is the area between opposing lanes of traffic, excluding turn lanes. Medians can either be open (pavement markings only) or they can be channelized (raised medians or islands) to separate various road users.

Pedestrian Refuge Areas (or crossing islands)–also known as center islands, refuge islands, pedestrian islands, or median slow points—are raised islands placed in the street at intersection or midblock locations to separate crossing pedestrians from motor vehicles.

Providing raised medians or pedestrian refuge areas at pedestrian crossings at marked crosswalks has demonstrated a 46 percent reduction in pedestrian crashes. Installing such raised channelization on approaches to multi-lane intersections has been shown to be particularly effective.

Providing raised medians or pedestrian refuge areas at pedestrian crossings at marked crosswalks has demonstrated a 46 percent reduction in pedestrian crashes. Installing such raised channelization on approaches to multi-lane intersections has been shown to be particularly effective.

At unmarked crosswalk locations, medians have demonstrated a 39 percent reduction in pedestrian crashes. Medians are especially important in areas where pedestrians access a transit stop or other clear origin/destinations across from each other.

Encourage your State to consider raised medians (or refuge areas) in curbed sections of multi-lane roadways in urban and suburban areas, particularly in areas where there are mixtures of a significant number of pedestrians, high volumes of traffic (more than 12,000 ADT) and intermediate or high travel speeds. Medians/refuge islands should be at least 4 feet wide (preferably 8 feet wide for accommodation of pedestrian comfort and safety) and of adequate length to allow the anticipated number of pedestrians to stand and wait for gaps in traffic before crossing the second half of the street.

A Review of Pedestrian Safety Research in the United States and Abroad, pp 85-86

http://www.walkinginfo.org/library/details.cfm?id=13

Pedestrian Facility User's Guide: Providing Safety and Mobility, p. 56

http://drusilla.hsrc.unc.edu/cms/downloads/PedFacility_UserGuide2002.pdf

Safety Effects of Marked vs. Unmarked Crosswalks at Uncontrolled Locations, p. 55

http://www.walkinginfo.org/library/details.cfm?id=54

Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities, American Association of State Highway and Transportation officials, 2004 [Available for purchase from AASHTO.]

Office of Safety:

Tamara Redmon

tamara.redmon@dot.gov

202-366-4077

FHWA Office of Safety R&D:

Ann Do

ann.do@dot.gov

202-493-3319

FHWA Resource Center:

Rudy Umbs

rudy.umbs@dot.gov

708-283-3548

Q&A – Medians and Pedestrian Refuge Areas

Q: For the purposes of providing pedestrian refuge areas, what is considered a “significant” number of pedestrians?

A: There is no “magic number” of pedestrians that every agency should consider to be significant. Each agency should evaluate a location in terms of the pedestrian demand; that is, review the site to determine if pedestrians regularly try to cross the street. Such pedestrian crossing volumes will differ greatly from one jurisdiction to another. The other consideration should be whether pedestrian crashes have occurred, involving pedestrians trying to cross the street. Having several pedestrians struck while crossing a multi-lane road should be a reason for strongly considering adding a raised median or median island.

Q: Are pedestrians more at risk where there are lower numbers of pedestrians (referring to the recommendation that refuge areas be provided where there are a significant number of pedestrians).

A: There is evidence that an increase in pedestrian volume will likely result in a reduction in the pedestrian crash “rate” (i.e., pedestrian crashes per number of pedestrians crossing), although the actual number of pedestrian crashes will generally increase as the pedestrian exposure increases. Although it is logical to assume that drivers will slow down and be more respectful of pedestrians in situations where more pedestrians exist, it is unclear to what extent that this is actually the case. The general recommendation to provide refuge areas where there are “significant” numbers of pedestrians is an attempt to balance costs with anticipated safety benefi ts, each of which can vary based on the particular location.

Q: Where there are no curbs, but the roadway, pedestrian and traffic volume criteria are otherwise met, should median refuge areas be provided?

A: The guidance was meant to provide some middle ground between the need to improve safety to the maximum extent possible and the reality that localities won't be able to provide medians everywhere due to the cost, ROW constraints, etc. That said, pedestrian crash risk increases in situations where traffic volumes increase on multi-lane roads, particularly above an ADT of approximately 10,000, regardless of whether a curb exists or not. Therefore, roadway sections should be judged in terms of needs for median refuge islands based primarily on higher number of lanes greater traffic volume, higher vehicle speeds, and greater number of pedestrians who try to cross. In summary, if the criteria are otherwise met, medians should be provided in uncurbed sections meeting the criteria as well if the locality is able to provide them.

Several types of pedestrian* walkways have been defined:

The presence of a sidewalk or pathway on both sides of the street corresponds to approximately an 88 percent reduction in “walking along road” pedestrian crashes.Providing paved, widened shoulders (minimum of 4 feet) on roadways that do not have sidewalks corresponds to approximately a 71 percent reduction in “walking along the road” pedestrian crashes. “Walking along the road” pedestrian crashes typically are around 7.5 percent of all pedestrian crashes (with about 37 percent of the 7.5 percent being fatal and serious injury crashes).

A number of studies have also shown that widening shoulders reduces all types and all severity of crashes in rural areas. Reductions of 29 percent for paved and 25 percent for unpaved shoulders have been found on 2-lane rural roads where the shoulder was widened by 4 feet. In addition, shoulder widening and paving provides space for rumble strips.

*Pedestrian: Any person traveling by foot, and any mobility impaired person using a wheel¬chair.USDOT policy calls for bicycling and walking facilities to be incorporated into all transportation projects unless exceptional circumstances exist (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/)

Encourage your State to provide and maintain accessible sidewalks or pathways along both sides of streets and highways in urban areas, particularly near school zones and transit locations, and where there is frequent pedestrian activity. Walkable shoulders (minimum of 4 feet stabilized or paved surface) should be provided along both sides of rural highways routinely used by pedestrians.

A Review of Pedestrian Safety Research in the United States and Abroad, pp 113-114.

A Review of Pedestrian Safety Research in the United States and Abroad, pp 113-114.

http://www.walkinginfo.org/library/details.cfm?id=13

An Analysis of Factors Contributing to 'Walking Along Roadway' Crashes: Research Study and Guidelines for Sidewalks and Walkways.

http://www.walkinginfo.org/library/details.cfm?id=51

Pedestrian Facility User's Guide: Providing Safety and Mobility, p. 56

http://drusilla.hsrc.unc.edu/cms/downloads/PedFacility_UserGuide2002.pdf

A US DOT Policy Statement Integrating Bicycling and Walking into Transportation Infrastructure

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/guidance/design.cfm

Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, 2004. [Available for purchase from AASHTO]

Office of Safety:

Tamara Redmon

tamara.redmon@dot.gov

202-366-4077

FHWA Office of Safety R&D:

Ann Do

ann.do@dot.gov

202-493-3319

FHWA Resource Center:

Rudy Umbs

rudy.umbs@dot.gov

708-283-3548

Q&A - Walkways

Q: What is the basis for recommending a 4-ft-wide walkable shoulder in rural areas?

A: The 4 foot width of walkway or walkable shoulder is a suggested “absolute minimum” distance away from the travel lane that is needed to provide at least some level of separation between motorists with pedestrians who will be walking along the road. Having little or no “walkable” area along the side of the road is likely to result in pedestrians walking on the pavement edgeline or in the travel lane, which can be deadly to pedestrians, particularly at night or other times when visibility is low (fog, dawn or dusk, rainy conditions, etc.). Obviously, providing as much separation as feasible can further enhance pedestrian safety even beyond a 4-foot walkable shoulder. Certainly having an 8-or 10-foot shoulder is much preferred and will further reduce the likelihood of a pedestrian being struck by an errant vehicle.

FHWA-NHI-139004: Principles of Effective Commercial Motor Vehicle (CMV) Size and Weight Enforcement

Instructor-led Training

Principles of Effective Commercial Motor Vehicle Size and Weight Enforcement is a 2-day course intended to provide advanced, in-depth, understanding of Federal motor vehicle size and weight regulations and the importance of State-level vehicle size and weight enforcement programs. This course targets transportation professionals responsible for overseeing the preservation of Federal and State highway assets through annual VSW enforcement planning and Federal certification, as well as personnel directly involved in commercial VSW enforcement. The course provides techniques and strategies designed for those individuals working to implement VSW enforcement programs.

Bud Cribbs

(703) 235-0526

bud.cribbs@dot.gov

FHWA-NHI-134096: TCCC Basics of Cement Hydration

Web-based Training

This training was prepared by the Transportation Curriculum Coordination Council (TCCC) in partnership with NHI to review integrated materials and construction practices for concrete pavement. This module covers how a concrete mixture changes from a plastic state to become a solid concrete slab in a relatively short period of time. Central to this transformation is a complex process called hydration, an irreversible series of chemical reactions between water and cement.

Danielle Mathis-Lee

(703) 235-0528

danielle.mathis-lee@dot.gov

FHWA-NHI-131112: Principles and Practices for Enhanced Maintenance Management Systems

Web-conference and Web-based Training

The course consists of 3 live Web sessions with several self-study modules.

NHI developed this course to save participants time and money on travel.

It covers the same content as the instructor-led training FHWA-NHI-131107, but because of the online delivery method, it is substantially less expensive.

This course is an introduction to the methods and practices used in an enhanced maintenance management system (MMS) to effectively maintain and operate a highway network.

It provides participants with the principles and practices of using MMS effectively and illustrates efficient maintenance and operation of a highway network.

Throughout the course, participants are provided with activities and assignments specific to using MMS.

Marty Ross

(703) 235-0534

IHSDM - The 2009 Beta Release of Crash Prediction Module (CPM)

The 2009 Beta Release of the Crash Prediction Module (CPM) to support the upcoming Highway Safety Manual Part C - Predictive Methods is now available for free downloading at www.ihsdm.org. The Crash Prediction Module is one of the six existing modules available from FHWA's 2008 Public Release of Interactive Highway Safety Design Model (IHSDM). This 2009 Beta Release of CPM is intended to be the faithful implementation of the upcoming Highway Safety Manual (HSM), Part C – Predictive Methods. We updated the algorithms of CPM/IHSDM two-lane rural highways module (HSM - Chapter 10) and introduce newly developed multi-lane rural highways module (HSM - Chapter 11) and urban and sub-urban arterials module (HSM - Chapter 12). For more information on the Highway Safety Manual, please go to: www.highwaysafetymanual.org.

The 2008 Public Release (Version 5.0.2) of IHSDM is a suite of software analysis tools for evaluating safety and operational effects of geometric design decisions on two-lane rural highways. It includes six evaluation modules, namely Policy Review, Crash Prediction, Design Consistency, Intersection Review, Traffic Analysis, and a fully-functioning beta version of Driver/Vehicle Module. For more information of this 2008 IHSDM please go to: IHSDM WiKi: http://www.ihsdm.org/wiki/Welcome.

Please be advised that the 2009 Beta Release of CPM and the existing 2008 Public Release of IHSDM should be installed and operated individually (i.e. do NOT install the 2009 CPM Beta Release “over” the 2008 Public Release). For existing registered IHSDM users, please use your IHSDM username and previously assigned password to access and download this extended CPM module. For new users, please look for “download registration” at www.ihsdm.org.

For free technical support of both of this 2009 Beta Release of CPM and the 2008 public release of IHSDM, please e-mail IHSDM.Support@fhwa.dot.gov or call 202-493-3407.

| Sept 20 - 26 | NATIONAL | Child Passenger Safety Week |

|---|---|---|

| Sept 21 - 25 | Stockholm, Sweden | ITS World Congress |

| Sept 21 - 22 | Rehoboth, Delaware | Task Force 13 & AASHTO - Technical Committee for Roadside Safety (TCRS) meeting |

| Oct 3 - 7 | Denver, CO | International Association of Chiefs of Police 116th Annual Conference http://www.theiacp.org/ |

| Oct 5 - 9 | NATIONAL | Drive Safely to Work Week |

| Oct 6 - 9 | Charleston, SC | American Road and Transportation Builders Association National Convention |

| Oct 7 | NATIONAL | Walk to School Day http://www.walktoschool.org/ |

| Oct 19 - 23 | NATIONAL | National School Bus Safety Week |

| Oct 22 - 27 | Palm Desert, CA | 2009 AASHTO Annual Meeting http://www/transportation.org/meetings/181.aspx |

| Nov 2 - 8 | NATIONAL | Drowsy Driving Prevention Week |

| Nov 15 - 18 | New Orleans, LAD | 2009 National Highway Rail Grade Crossing Safety Conference, http://tti.tamu.edu/conferences/rail09/ |

The Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA) presented its national highway safety awards during its Annual Meeting in Savannah. GHSA represents state highway safety agencies across the country.

GHSA presented five Peter K. O'Rourke Special Achievement Awards for notable achievements in highway safety in calendar year 2008. These Awards are named in honor of former GHSA Chairman and Californian Peter K. O'Rourke.

Winners:

Illinois Operation Teen Safe Driving Program, recognizing the Illinois Department of Transportation's Division of Traffic Safety for its unique, statewide teen driving program. This program has reached more than 99,000 teens and translated into lives being saved. Teen fatalities decreased from 155 in 2007 to 93 in 2008. The state credits this program, along with a new Graduated Driver License (GDL) law, for the dramatic drop in teen deaths. The program was supported by the Ford Driving Skills for Life program and The Allstate Foundation.

Indiana Supreme Court, Division of State Court Administration Judicial Technology & Automation Committee, for the development of a uniform, electronic ticketing system to enhance the efficiency and consistency of the traffic ticketing process in Indiana. Prior to this new system, Indiana's 92 counties struggled with paper tickets that did not provide any standardization or uniformity. Too often, important information was not collected. With the new system, efficiency is greatly enhanced, and police productivity has increased substantially.

Maryland's Task Force to Combat Driving Under the Infl uence of Drugs and Alcohol, for its efforts in assessing the status and progress of statewide efforts to combat impaired driving, identifying deficiencies, proposing solutions, and submitting a comprehensive report to the Governor and General Assembly. Forty-two proposed recommendations were submitted, which included improvements in engineering, enforcement, intervention, treatment, education and the courts. Seven legislative initiatives were included. Four of these have already become law. This effort is a model for states that want to review their progress in addressing impaired driving.

New Jersey Teen Driver Study Commission, for its work in assessing the state of teen driving in New Jersey and making recommendations to reduce the number of teen driver crashes and fatalities. The Commission's fi nal report included 47 recommendations, many of which were new and innovative. The Commission has had a substantial impact: already, new laws have been passed requiring a teen driver decal, lowering the curfew for provisional drivers to 11 p.m., and limiting the number of teen passengers to one unless a parent or guardian is present. This effort is a model for other states that want to comprehensively address the teen driving issue.

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, for its year-long series, “Wasted in Wisconsin.” Forty-nine journalists traveled the state and told the story of the abuse of alcohol and the profoundly tragic impact it has had on Wisconsin residents. The series generated substantial discussion throughout the state. While it is too early to assess legislative impact, more than 30 different legislative enhancements have been proposed. In today's economy, amid the decline of print journalism, it is rare for a newspaper to devote so much space to the issue of drunk driving - particularly a year-long series. “Wasted in Wisconsin” was a brave endeavor that will translate into lives being saved.

More detailed descriptions about the winners are available online at http://www.ghsa.org/html/meetings/awards/09.index.html.

The Association's highest honor, the James J. Howard Highway Safety Trailblazer Award goes to Illinois State Senator John J. Cullerton of Chicago. Senator Cullerton serves as President of the Illinois State Senate. Throughout his 30-year career in the Illinois State Legislature, Senator Cullerton has amassed a traffic safety record likely surpassing that of any state legislator in the nation. He has led the effort in the state to enact safety legislation on a variety of issues, including: child passenger safety; primary seat belt use; mandatory motorcycle helmet use; .08 Blood Alcohol Content (BAC); graduated licensing; and alcohol interlock laws.

GHSA also presented the Kathryn J.R. Swanson Public Service Award posthumously to Kevin E. Quinlan, who spent 35 years of exemplary service with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the National Transportation Safety Board. Mr. Quinlan was a dedicated public servant who diligently worked to improve the safety of our roadways.