U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Definitions of traffic calming have varied from publication to publication over the years. The following "definition," which has been developed by FHWA and ITE for this ePrimer, is a robust description that encompasses the many aspects of traffic calming:

The primary purpose of traffic calming is to support the livability and vitality of residential and commercial areas through improvements in non-motorist safety, mobility, and comfort. These objectives are typically achieved by reducing vehicle speeds or volumes on a single street or a street network. Traffic calming measures consist of horizontal, vertical, lane narrowing, roadside, and other features that use self-enforcing physical or psycho-perception means to produce desired effects.

A variety of definitions are commonly used in the traffic calming field and although the exact wording may differ, the essence remains; traffic calming reduces automobile speeds or volumes, mainly through the use of physical measures, to improve the quality of life in both residential and commercial areas and increase the safety and comfort of walking and bicycling.

Traffic calming has helped to increase the quality of life in urban, suburban, and rural areas by reducing automobile speeds and traffic volumes on neighborhood streets. The implementation of traffic calming on residential streets is illustrative of the tools that traffic engineers and planners can use to meet broader societal needs to facilitate the safe and efficient movement of all street users. Traffic calming measures can help to transform streets and aid in creating a sense of place for communities.

The practice of traffic calming has evolved in recent years from a neighborhood-specific treatment to an integral part of complete streets and other bicyclist/pedestrian-related projects. Although mostly known as a neighborhood-specific initiative, traffic calming can be implemented on different street types and in different areas, including commercial settings and rural areas. Neighborhood traffic calming as a stand-alone approach to address traffic concerns isn't as prevalent as in past decades, with fewer new or updated neighborhood traffic calming programs due to funding constraints. However, the desire of citizens to slow automobile speeds or reduce volumes on streets adjacent to their homes has not decreased, and neighborhood traffic calming programs often provide the most effective way for residents to request traffic calming on residential streets.

Traffic calming within neighborhoods is unique as local residents are often the primary group interested in addressing automobile speeds and traffic volumes. Therefore, it is important that there continue to be a clear process for the planning, evaluation, and implementation of neighborhood traffic calming. As a comparison, the other major uses of traffic calming in cities are driven by multiple facets, whether by the bicyclist advocacy community in the case of bicycle boulevards or by safety advocates in the case of complete streets projects, and emerging Vision Zero policies, as examples. Neighborhood traffic calming continues to provide residents with a means to address traffic concerns in their neighborhoods.

A video that presents an overview of the issues addressed by traffic calming and the wide range of available measures can be accessed at the following hyperlink: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bkz026kKpRU (Source: Streetfilms)

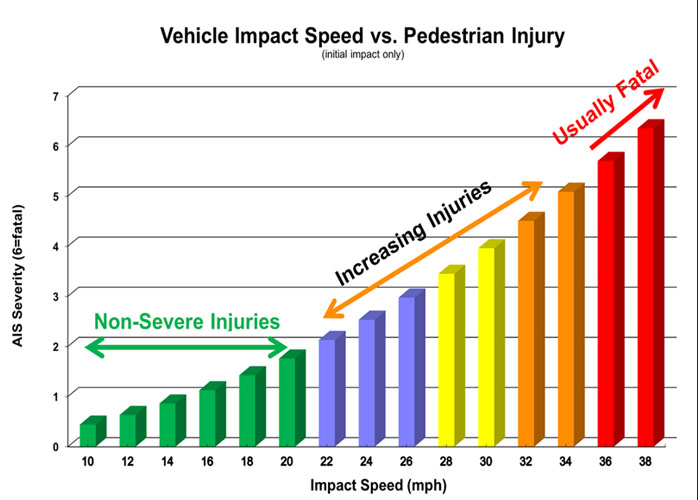

The importance of reducing vehicle speeds cannot be overstated in an area where there is potential for conflict between a pedestrian and a motor vehicle. The slower the speed of the motor vehicle, the greater the chances are for survival for the pedestrian. If struck by a motor vehicle travelling at a speed of 20 miles per hour or less, a pedestrian is typically not permanently injured. If struck by a motor vehicle travelling at a speed of 36 miles per hour or more, a pedestrian is usually fatally injured (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Speed/Pedestrian Injury Severity Correlation

(Source: C. E. "Rick" Chellman)

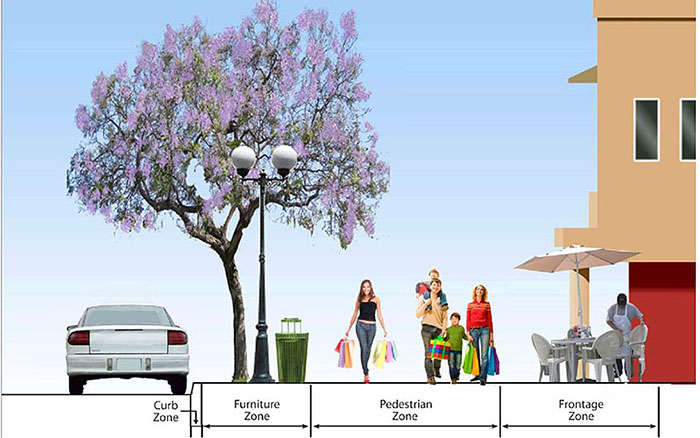

In order to effectively improve pedestrian safety and mobility, a traffic calming measure needs to be integrated with, supplement, and not conflict with the overall pedestrian network and system. This proper application and integration requires the analyst to understand and appreciate the full scope of services provided by a sidewalk. A sidewalk is comprised of four distinct zones: frontage zone, pedestrian (or walking) zone, furniture zone, and curb (or edge) zone. Figure 2.2 is an illustration of a typical sidewalk cross-section in a mixed-use or commercial area.

Figure 2.2. Sidewalk Zones in a Typical Mixed-Use or Commercial Area

(Source: California Model Design Manual for Living Streets and Michele Weisbart)

The frontage zone provides:

A typical frontage zone width ranges between 18 and 30 inches (plus 8 feet or more for cafe seating).

The pedestrian zone is the throughway part of the sidewalk, where pedestrians walk and otherwise ambulate through an area. It must be kept clear of all fixtures and obstructions. The pathway must comply with Americans with Disabilities guidelines. A typical pedestrian zone width ranges between 5 and 8 feet.

The furniture zone is located between the pedestrian and edge zones. It contains fixtures that are integral to the function of the sidewalk, but that must be placed apart from the pedestrian zone. It can include street trees, bus stops and shelters, utility poles and boxes, lamp posts, bicycle racks, signs, benches, parking meters, and waste receptacles. A typical furniture zone width ranges between 4 and 8 feet.

The curb zone provides curbing that prevents water from encroaching on the sidewalk area and provides a clear demarcation between the sidewalk and motor vehicle travel and parking lanes. A typical curb zone width ranges between 6 and 18 inches.

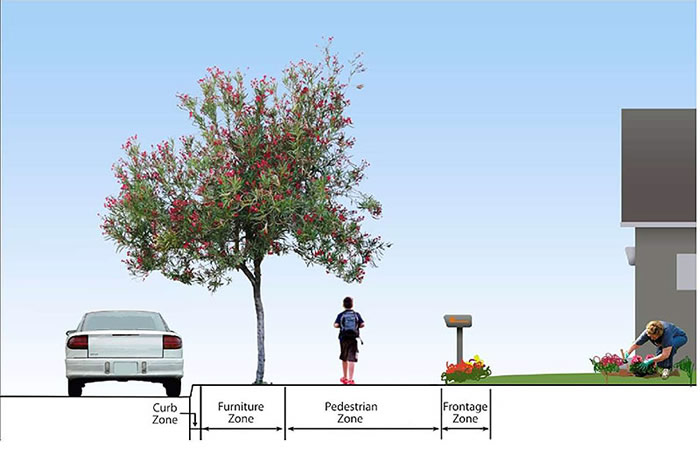

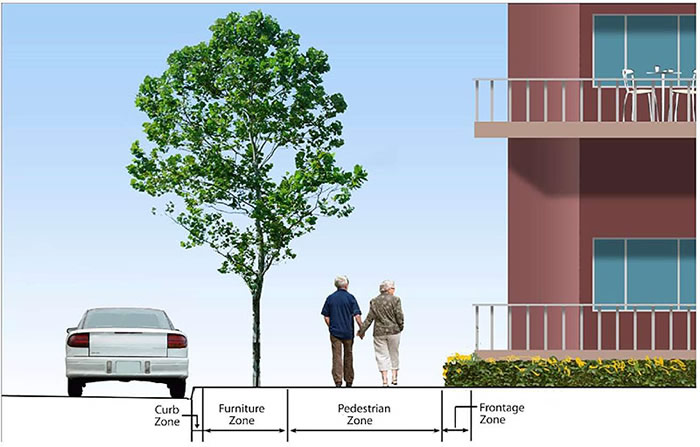

In a purely residential setting, the sidewalk zones are often simplified, but are still identifiable (as illustrated in Figures 2.3 and 2.4).

Figure 2.3. Sidewalk Zones in a Typical Low/Medium-Density Residential Area

(Source: California Model Design Manual for Living Streets and Michele Weisbart)

Figure 2.4. Sidewalk Zones in a Typical Medium/High-Density Residential Area

(Source: California Model Design Manual for Living Streets and Michele Weisbart)

Traffic calming is often an integral part of many other transportation initiatives, such as context sensitive solutions, shared streets, and complete streets, among others. Outside of residential areas, traffic calming measures often go completely unnoticed by motorists. For example, many walkable downtown commercial areas have traffic calming measures woven in to the built transportation network to help reduce vehicle speeds and volumes, such as corner extensions and median islands. The following are examples of uses of traffic calming measures outside of the traditional neighborhood focus.

Traffic calming can be a key element of a successful complete street, which is a roadway that is designed and functions to enable safe travel by all users of all abilities. A complete street design can include the use of traffic calming measures primarily to enhance the facilities for bicyclists, pedestrians, and transit uses. The automobile speed reduction benefits of the individual measures are an important part of the layout, but typically are less important than in neighborhood traffic calming. Many of the bicyclist and pedestrian amenities that are common in a complete street project have been used in traffic calming for years, such as corner extensions, chokers, and median islands. The inclusion of these measures in urban complete streets projects highlights a general shift in cities from neighborhood to urban traffic calming.

Traffic calming can help in implementation of context sensitive solutions by minimizing the negative effects of vehicle travel to improve safety and mobility for all street users. A major component of context sensitive solutions is a transportation facility that fits its settings. Traffic calming fits this approach as it is often built into an existing roadway to blend into the surroundings. For example, traffic calming measures such as chokers and corner extensions fit the setting by reducing portions of the roadway not used by the traveling public and better allocate that space to the safety and mobility of pedestrians.

Shared streets and pedestrian-priority streets (also referred to as living streets) are locations where the number of pedestrians crossing the street outnumber the vehicle usage. By necessity, the roadway features reflect the need to accommodate pedestrian activity and frequent crossings. However, the roadways remain open to vehicle traffic and deliveries, although the vehicle traffic is minimal and travels at slow speeds. Horizontal deflections and street width reductions are often included in shared streets. Raised intersections can also be used to mark the beginning of a shared street, particularly if the entire roadway is not brought up to the pedestrian level.

The concept of a shared street is commonly associated with the "woonerfs." Originating in the Netherlands, a woonerf is a roadway where the vehicle speed limit is the walking speed and the roadway is typically designed to accommodate pedestrians as the highest priority transportation mode. While individual traffic calming measures can help to reduce vehicle speeds on these street types, traffic calming programs often have included a woonerf as a complete treatment.

The complete streets movement has led, in part, to greater standardization of traffic calming measures by cities. The emergence of complete streets and urban street design guidelines for cities has provided jurisdictions the opportunity to create specific design guidelines for traffic calming measures. The complete streets guidelines and urban street design guidelines often identify various roadway types, with applicable traffic calming measures identified for each type, thereby allowing the design guidelines to be tailored specifically to achieve the goals of the complete streets policies for each street.

Traffic calming involves trade-offs; finding a balance between the need to provide an efficient transportation network and maintaining a livable and safe environment for bicyclists, pedestrians, and other street or street-adjacent users. The challenge of traffic calming is selecting the appropriate measures and locations to reach that balance.

Traffic calming issues have shifted over the decades as communities across the country have embraced the concept of installing traffic calming on their roadways. Rapid response needs of emergency service providers remains a concern and policy to resolve such concerns has been developed. Funding of traffic calming however, continues to be an issue for many traffic calming programs and plans.

Often in neighborhood traffic calming, meeting the desires of the neighborhood residents is a challenge. Residents may want slower vehicle travel speeds through their neighborhoods, but mobility desires can be at odds with that goal. A traffic calming measure seen as necessary by some may be seen as a nuisance by others. For example, residents may object to a traffic calming measure being placed directly in front of their property. The placement of measures adjacent to property lines may reduce this potential negative reactions of residents. Approaches exist to help reach a neighborhood consensus on a traffic calming plan.

Traffic calming can also affect a variety of entities that rely on the transportation network for efficient movement. Some of the agencies most challenged by the implementation of traffic calming measures include fire departments and emergency response agencies. Other entities that may be affected by traffic calming include transit agencies, police departments, school districts, snow removal, and waste collection.

Few jurisdictions have been successfully sued over liability issues related to traffic calming measures. The successful lawsuits have generally been the result of improper or inadequate maintenance of signs or pavement markings, not because a traffic calming measure was determined to be inherently unsafe.

It is the duty of the public entity to make sure the roadway system is safe for the intended use of that roadway. In order to establish negligence on the part of a public entity, the injured party must establish (1) that the government agency owed a duty to that person, (2) that the duty was breached by an act or a failure to act, (3) that the breach of duty was the proximate cause of the injury or loss to the complainant, and (4) that the government had adequate notice of the dangerous condition.

In order to minimize the potential for any liability, a public agency should develop and maintain documentation of every step in the traffic calming program process.

Property Access

In general, a property owner has a right of access to a non-limited access public roadway, but not necessarily at all points along the roadway. The standard language is for reasonable and conventional ingress and egress to the property.

A traffic calming measure, such as a median island or median barrier, could affect accessibility of a property. If the hindrance is permanent and substantial, the measure could be considered a taking.

For a traffic calming measure (or series of measures) to be successful and effective, the government entity should involve directly-affected property owners in the identification of a problem to be solved, identification of alternative potential solutions to the problem, analysis of solutions, selection of a design concept, and finalization of the traffic calming measure design.

One common issue that arises is the assignment of maintenance responsibilities when the curb line is altered with the introduction of some traffic calming features (such as a corner extension, choker, lateral shift, or chicane).

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires that traffic calming measures be designed, installed, and maintained so that the mobility of an individual with disabilities is not impeded. In general, any traffic calming measure that improves pedestrian safety and mobility will likewise improve safety and mobility for a person with a disability if designed to comply with ADA guidelines.

The field of traffic calming has evolved since the 1970s and has become commonplace in many municipalities. Although various traffic calming techniques date back to the late 1940s or early 1950s, it wasn't until FHWA's State of the Art Report: Residential Traffic Management in 1980 that the magnitude to which traffic calming had caught on was realized. This publication found that over 120 jurisdictions in North America had experience with traffic calming in one form or another by 1978.

In 1999, ITE published Traffic Calming: State of the Practice, which became a primary traffic calming reference in the U.S. The book was widely used for its robust data on the effectiveness of traffic calming measures, its design details for various traffic calming measures, and illustrations/photos of a wide variety of measures. The publication also contained background information on legal authority and liability, emergency response and other agency concerns, and impacts of traffic calming, among other subjects.

Traffic Calming: State of the Practice made a significant impact on the landscape of traffic calming in the engineering profession and since then numerous additional manuals and articles have been published to assist planners and engineers in implementing traffic calming on public roadways. In 2009, the American Planning Association published the U.S. Traffic Calming Manual, which combined much of the information from Traffic Calming: State of the Practice and the Traffic Calming chapter of the 6th Edition of the Traffic Engineering Handbook, with updates provided throughout. Information contained in the documents has been and continues to be integrated into practice.

As traffic calming is implemented on the public roadway system, there are established guidance documents that should be used as references for some design aspects of traffic calming. A sample of the design practice documents that relate to the ePrimer include: the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets ("Green Book"), FHWA Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) Urban Street Design Guide, AASHTO Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities, and ITE Guidelines for the Design and Application of Speed Humps.

The ePrimer text references a pair of FHWA documents that present information on the effects of a wide range of measures (including traffic calming) on pedestrian and motorist safety: Engineering Speed Management Countermeasures: A Desktop Reference of Potential Effectiveness in Reducing Crashes and Engineering Speed Management Countermeasures: A Desktop Reference of Potential Effectiveness in Reducing Speed. The FHWA Crash Modification Factors (CMF) Clearinghouse website provides CMFs for several traffic calming measures, including speed humps, speed tables, raised crosswalks, median islands, on-street parking, and road diets. [provide hyperlink to website: http://www.cmfclearinghouse.org/]

The information provided in this ePrimer makes use of a variety of state and local guidance documents, including: