Module 2: Fundamentals of Transportation Planning

The purpose of this module is to provide a basic introduction to transportation planning, especially for safety planners, stakeholders, and other audiences. It is designed to inform safety practitioners with adequate knowledge of the planning process and exhibit opportunities for incorporating safety as a consideration in all phases of the transportation planning process. It defines the basic steps of the transportation planning process by identifying the stakeholders, legislation, plans and processes, data and analysis methods, and funding.

Introduction

Transportation planning defines a State, region, or community’s vision for the future. It is a collaborative, data-driven process carried out by transportation planners at Departments of Transportation (DOT), Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO), public transit agencies, and local and Tribal governments. Transportation planning is a cooperative, performance-driven process by which long- and short-range transportation improvement priorities and investments are determined. MPOs, States, and transit operators conduct transportation planning, with active involvement from the traveling public, the business community, community groups, environmental organizations, and freight operators. It includes 1) a comprehensive consideration of possible strategies; 2) an evaluation process that encompasses diverse viewpoints; 3) the collaborative participation of relevant transportation-related agencies and organizations; and 4) open, timely, and meaningful public involvement.

The 3C planning process (continuing, comprehensive, and cooperative) dates back to the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962. It is designed to engage the public and stakeholders in establishing shared goals and a vision for the community. Planners use various tools to forecast population trends, employment growth, and projected land use and to identify major transportation needs and opportunities for investment. This process requires planners to establish existing conditions and needs, review available funding resources, establish transportation performance measure targets and goals, and develop strategies to meet the goals. The information is documented in the Statewide Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) and Metropolitan Transportation Plans (MTP). The Performance-Based Planning Process (PBPP), provides tools to establish system performance targets based on informed investment decisions, which are documented in the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) at the State level and the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) at the MPO level.

National Performance Goals

23 U.S.C. §150 specifies seven national goal areas for the Federal-Aid Highway Program:

- Safety.

- Infrastructure condition.

- Congestion reduction.

- System reliability.

- Freight movement and economic vitality.

- Environmental sustainability.

- Reduced project delivery delays.

Transportation safety is a required factor in the planning process. Safety specialists play a significant role in transportation planning and this role can be enhanced if they have working knowledge and understanding of transportation planning job functions, products, and plans. The tools and methods developed by safety practitioners provide data and input when developing short- and long-term transportation safety goals and strategies. Better collaboration, communication, and coordination between safety specialists and transportation planners ensures the integration of safety into the transportation planning process and optimizes opportunities to address the most critical transportation safety issues.

Transportation Planning Stakeholders

Transportation planning covers a range of topics, disciplines, and stakeholders from the traveling public, private industry, community advocates, and local transportation agencies and operators. According to 23 U.S.C. §134 and §135, transportation planning processes should provide reasonable opportunity for involvement from interested parties, which might include representatives of public transportation, employees, public ports, providers of freight, providers of transportation (including intercity bus operators, employer-based commuting programs, transit benefit program, parking cash-out program, shuttle program, or telework program), users of public transportation, users of pedestrian walkways and bicycle transportation facilities, representatives of the disabled, and other interested parties.

State DOTs and MPOs use a variety of methods to engage the stakeholders in the planning process to comply with public involvement practices. The techniques include holding public meetings at convenient and accessible locations and times, employing visualization techniques to describe plans; and making public information available in electronically accessible formats and means (e.g., World Wide Web, social media, and phone-based/virtual information sessions). Task forces, focus groups, and technical committees assume various roles in the planning process and are used to gather information and provide input on the transportation system and priorities. Specific methods and information transportation planners can glean from safety practitioners and stakeholders include the following:

- Data—Planners utilize crash data, but safety specialists are familiar with crash data and other data sets that may be useful to planning (e.g., demographics and health data, the results of behavioral surveys, or effective education/enforcement programs). Planners can utilize this information to make decisions about infrastructure investments.

- Safety Expertise and Knowledge—Safety practitioners provide knowledge relevant to safety areas. They are more likely to be involved in the Strategic Highway Safety Plans (SHSP) process. Sharing this knowledge will help shape the Statewide LRTPs, MTPs, as well as Statewide and metropolitan transportation improvement programs (S/TIP).

- Information Sharing—Safety practitioners can share information about upcoming enforcement and education campaigns, safety workshops/meetings, behavioral research, and the safety performance of planned infrastructure investments with transportation planners, encouraging them to learn from and leverage safety opportunities as part of their job responsibilities. This information exchange also can highlight the need to include specific safety-related projects in the Statewide LRTP/MTP or S/TIP.

- Statewide LRTP/MTP Update—For a plan update, State DOTs and MPOs utilize outreach to solicit input from different stakeholder groups. They may form specific committees, visit stakeholders one on one, or host workshops. Safety practitioners can contact the State DOT Planning Office or MPO to obtain more information on the next update cycle and opportunities to participate. A safety committee or ad hoc task force may be convened to gather information on the State or region’s traffic safety challenges and potential countermeasures. The DOT or MPO’s Public Participation Plan could include specific strategies to collect information on safety issues and needs during the public involvement process and opportunities to integrate the collected information into the LRTP, MTP, and SHSP.

- MPO Committees—All MPOs have Transportation Policy Committees (TPC) or Policy Boards and most have Technical Advisory Committees (TAC). These are used to inform and make decisions about all transportation planning topics. TPCs and TACs are actively engaged in the development of the MTP and TIP. Safety practitioners’ attendance at these meetings maximizes opportunities to educate elected officials and contribute information about regional safety issues and programs, other planning efforts (e.g., freight plans, transit studies, corridor plans, bicycle and pedestrian plans, etc.) or an update on SHSP-related topics.

- Special Topic Committees—Some MPOs have specific safety committees or task forces to discuss behavioral or infrastructure-related topics.

Planning Legislation

This section explains the legislation and Federal rules governing the Statewide, nonmetropolitan, metropolitan, and transit planning processes.

Statewide and Nonmetropolitan Transportation Planning

The State may establish Regional Transportation Planning Organizations (RTPO) to assist them in carrying out the Statewide and nonmetropolitan transportation planning process. The RTPO consists of nonmetropolitan area local officials and transportation system operators who volunteer and represent their jurisdictions in the Statewide planning process.

The Statewide and nonmetropolitan transportation planning process requirements are described in 23 U.S.C. §135. States must develop transportation plans and programs for all areas of the State, including nonmetropolitan areas. State DOTs cooperating with existing Regional Transportation Planning Organizations (RTPO) may conduct transportation planning for nonmetropolitan areas. The plans and programs provide for transportation facilities, which function as an intermodal State transportation system. The intent of the process is to inform investment decisionmaking and considers all modes of transportation. States are required to coordinate with the metropolitan transportation planning activities. The legislation outlines the transportation plans and products States must develop, and the government agencies and public stakeholders who should be engaged.

Metropolitan Transportation Planning

23 U.S.C. §134 and the planning regulations (23 CFR 450.306) establishes the required transportation planning factors that must be addressed in a metropolitan transportation plan, including operational and management strategies to improve performance by targeting congestion and improving safety of existing facilities. Safety considerations are included in several portions of the planning rule.

Transportation Planning Factors

This section defines key terms and explains the general requirements for States and MPOs to implement the transportation planning process. The key Federally required planning factors or considerations are the same for State DOTs and MPOs and include the following:

- Support the economic vitality of the United States, the States, nonmetropolitan areas, and metropolitan areas, especially by enabling global competitiveness, productivity, and efficiency.

- Increase the safety of the transportation system for motorized and nonmotorized users.

- Increase the security of the transportation system for motorized and nonmotorized users.

- Increase the accessibility and mobility of people and freight.

- Protect and enhance the environment, promote energy conservation, improve the quality of life, and promote consistency between transportation improvements and State and local planned growth and economic development patterns.

- Enhance the integration and connectivity of the transportation system across and between modes throughout the State, for people and freight.

- Promote efficient system management and operation.

- Emphasize the preservation of the existing transportation system.

- Improve transportation system resiliency and reliability and reduce (or mitigate) the stormwater impacts of surface transportation. (FAST Act expanded the scope of consideration of the metropolitan planning process to include this factor.)

- Enhance travel and tourism. (FAST Act expanded the scope of consideration of the metropolitan planning process to include this factor.)

Transit Planning

Transit planning is governed by the 49 U.S.C. Chapter 53, which provides funding to support public transportation; establishes standards for the state of good repair of public transportation infrastructure and vehicles; and promotes continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive planning that improves the performance of the transportation network. Statewide and metropolitan planning requirements for public transportation mirror those of 23 U.S.C. §134 and §135.

Transportation Plans and Processes

Legislation requires transportation planners to complete a Statewide LRTP, MTP, STIP, and TIP. State DOTs must also develop a State Planning and Research Guide (SP&R). MPOs also are required to develop a Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP). Transportation planners conduct other planning efforts based on State, regional, and local needs.

Table 2 summarizes the key transportation planning products. The transportation plans are described below.

| Who Develops? | Who Approves? | Time Horizon | Content | Update Requirements | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statewide LRTP | State DOT | State DOT | 20 years | Future Goals, Performance Measures, and Strategies | Not specified |

| MTP | MPO | MPO | 20 years | Future Goals, Strategies, and Projects | Every 5 years (4 years for nonattainment and maintenance areas) |

| STIP | State DOT | Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)/Federal Transit Administration (FTA) | 4 years | Transportation Investments | Every 4 years |

| TIP | MPO | MPO/Governor | 4 years | Transportation Investments | Every 4 years |

| UPWP | FHWA/FTA/MPO | MPO | 1 or 2 years | Planning Studies and Tasks | At least once every 2 years |

| State Planning and Research Work Program (SP&R) Guide | State DOT | FHWA | Not specified | Planning and Research | Not specified |

| Congestion Management Process (CMP) | MPO | MPO | Not specified | Congestion Management Objectives, Performance Measures, Strategies | Periodic review and update |

| Public Participation Plan | MPO | MPO | Not Specified | Public Engagement Strategies and Goals, Incorporating Input, Responding to Comments | Periodic review and update |

(Source: FHWA, The Transportation Planning Process Briefing Book, 2015 Update.)

Long-Range Transportation Plan/Metropolitan Transportation Plan

The Statewide LRTP/MTP is the primary transportation planning document required for the State DOT and MPO planning process. The plans are guided by the planning factors listed in 23 U.S.C. §134 and §135. Data analysis results, travel demand model outputs, and stakeholder/public input are used to identify the key roadway and transit issues and needs over the next 20-plus years. To meet those needs, MTPs detail capital improvements, and operations and maintenance projects that are fiscally constrained. Statewide LRTPs are not required to be fiscally constrained, but may include a financial plan. The Statewide LRTP may be a policy plan and may not include any specific projects. Statewide LRTPs/MTPs must include a description of the performance measures and performance targets, as described in 23 U.S.C. §150(b), used in assessing the performance of the transportation system, a system performance report, and subsequent updates evaluating the condition and performance of the transportation system, with respect to the performance targets.

Basic Elements of a Performance-Based LRTP

- Goals, performance measures, and desired trends or targets.

- Status report of current conditions.

- Assessment of needs.

- Investment priorities, policies, and strategies.

(Source: FHWA Performance-Based Planning Guidebook.)

Statewide LRTPs and MTPs address a wide range of transportation topics (e.g., air quality, environment, health, connectivity, and mobility), but an essential component is the safety of the transportation network. A range of approaches should be used to integrate safety into Statewide LRTP/MTPs. Safety may be addressed in the Statewide LRTP/MTP as a chapter or element and as project evaluation and selection criteria. Some MTPs address safety more broadly and develop a separate Regional Safety Plan, which provides a detailed 4 Es (Engineering, Education, Enforcement, and Emergency medical services) regional approach to safety improvement project development and implementation.

Statewide Transportation Improvement Program/Transportation Improvement Program

State DOTs and MPOs must develop STIPs/TIPs to identify projects that are to be funded, the implementation timeframe, and the available or committed funding sources for each project. The STIP/TIP is a financial program that describes the schedule for obligating funds to State, regional, and local projects over a four-year period.

The TIP draws from the pool of projects identified in the cost-feasible MTP that will be implemented over the next four years. Project selection criteria are then used to rank projects and match available funding streams to projects and strategies. Safety can be one of the project selection criteria. The TIP contains funding information primarily for roadway and transit projects, and is updated regularly to reflect the highest priority projects.

The STIP includes Federally funded transportation projects in consultation with MPOs, Tribal governments, and local governments in nonmetropolitan areas, and the public. Additional projects may come from the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), nonmetropolitan regional transportation planning organizations (RTPO or RPO), and transit operators.

Unified Planning Work Program

MPOs are required to prepare a Unified Planning Work Program. It is an annual or biennial statement of work identifying the planning priorities and activities to be carried out within a metropolitan planning area. MPOs list work relevant to safety in the UPWP, including upcoming safety plans or studies, data collection efforts, corridor studies, and development of the MTP and TIP.

State Planning and Research Program

State DOTs are required to prepare a State Planning and Research Program, which outlines how they will conduct their research and technology program with SP&R funds.

Congestion Management Process

Transportation Management Areas (TMAs) are required to develop and implement a CMP. TMAs are urbanized areas with populations exceeding 200,000.

The Congestion Management Process (CMP) is a structured process for analyzing congestion and air quality issues using a systematic and regionally accepted approach. The process includes development of congestion management objectives, establishment of multimodal transportation system measures, data collection, and system performance monitoring to determine the extent and duration of congestion, identification of strategies to manage congestion, implementation activities, and evaluation of strategies. A CMP is required in MPO urbanized areas with populations exceeding 200,000, known as Transportation Management Areas (TMA). The CMP is developed and implemented as an integrated part of the metropolitan transportation planning process. In TMAs designated as ozone or carbon monoxide nonattainment areas, Federal law prohibits projects that result in a significant increase in carrying capacity for single-occupant vehicles (SOV) from being programmed into these areas’ TIPs, unless the project is addressed in the CMP.

Public Participation Plan

Public involvement is a key component of the transportation planning process. To ensure the public’s needs and preferences are considered in the planning process, State DOTs and MPOs are required to document public and stakeholder engagement in transportation planning. State DOTs are required to document the process for Statewide engagement of the public and interested agencies and organizations. Public involvement should be coordinated with MPOs and RTPOs, when relevant. MPOs prepare Public Participation Plans (PPP), which describe how the MPO involves the public and stakeholder communities in transportation planning. The Transportation Planning Stakeholders section of this module describes the broad group of stakeholders to be engaged in the public involvement process and specific opportunities for safety specialists to engage in the transportation planning process.

Other Transportation Plans

While not required, State DOT and MPO planners undertake a range of planning activities to meet regional needs. These activities may include small area studies, corridor or subarea studies and plans, transit plans, freight and logistics plans, and bicycle and pedestrian plans. Safety is often addressed as part of a corridor or subarea plan to identify solutions for crashes in a specific area. Modal plans (e.g., bicycle and pedestrian, freight, and transit plans) explore opportunities to expand or enhance the use of the modes and often include safety components. Subarea plans propose growth and mobility options for a planning area, and also address the safety for all transportation users. 23 CFR 450.306(d)(4) requires State DOTs and MPOs to integrate directly or by reference the goals, objectives, performance measures, and targets described in other transportation plans and transportation processes. This includes applicable portions of the HSIP and SHSP.

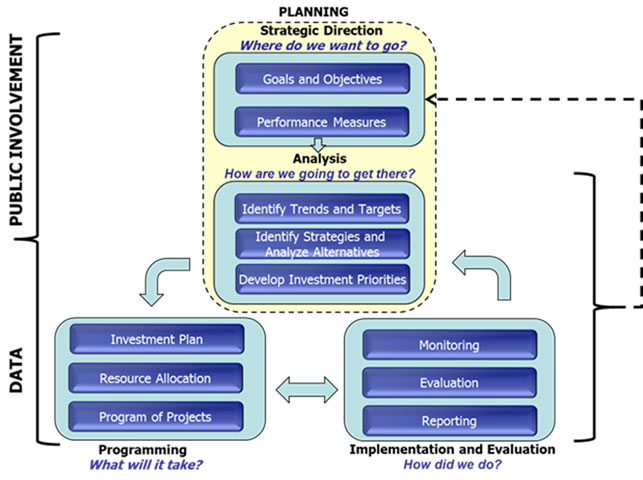

Agencies may conduct the planning processes differently, but all agencies use the framework similar to one outlined to the Performance-Based Planning Process (figure 1) to identify, prioritize, implement, and evaluate transportation projects. The process framework asks four basic questions with the expectation that the plans will answer them. The questions are: Where do we want to go? How are we going to get there? What will it take? and How did we do? Transportation safety can be addressed during the answers to each of the questions. State DOTs and MPOs are required to integrate other performance-based plans, such as the SHSP, into the transportation plans. Transportation planners participate in the performance management process by developing performance measures to address established goals, conducting data analysis and forecasting to determine the future performance of the transportation system, setting performance targets, identifying a plan of action to achieve desired results, tracking progress in achieving the targets, and developing performance reports.

Figure 1. Flowchart. Performance-based transportation planning process.

(Source: FHWA, The Transportation Planning Process: Key Issues, 2015 Update.)

The transportation planning process follows a process similar to the safety planning process summarized in Module 1. The process must be transparent and cooperative and includes several steps, such as collecting and analyzing data, establishing goals and objectives, identifying performance measures, prioritizing projects, implementing and evaluating projects and programs.

As with safety, transportation planning is multidisciplinary involving public involvement and coordination; however, in the case of transportation planning public involvement is foundational and required by law. Stakeholders and the public are involved and engaged, throughout the transportation planning process, in workshops, meetings, committees, focus groups or one-on-one meetings. The purpose of these outreach activities is to obtain input from stakeholders to be used during the process and to inform the resulting products (e.g., long-range transportation plans).

Goals address the key desired outcomes for the transportation network and are usually developed for all the major transportation modes and topic areas. State and regional transportation agencies often utilize the planning factors as a guide to establish goals. Objectives describe methods for achieving the goals, and performance measures track progress towards goals and objectives, which assess the extent to which goals and objectives are met. This is similar to the SHSP in the sense that emphasis areas, strategies, and actions provide the structure for the plan. Performance measures and targets are used to describe and assess the expected outcomes and achievements for safety.

To initiate a planning process, planners utilize data, forecasting tools, and stakeholder input to identify current and future transportation needs and develop investment priorities to address them. The analysis will consider factors such as travel modes, mobility, connectivity, environment, air quality, economy, health, security, and safety. Planners may also analyze alternatives or scenarios to produce the best program of projects for addressing future needs, given a fiscally constrained revenue budget.

States and MPOs use a project prioritization or programming process to evaluate potential projects-based on performance-based planning priorities. The prioritization process results in the S/TIP. The project prioritization process may involve a scoring system which incorporates planning factors and priorities. Once projects have been programmed into the S/TIP, they are eligible to begin further project development.

During the implementation and evaluation process, programs and projects in transportation plans are implemented and performance measures are used to understand how the projects impact system performance goals. Finally, planners and decisionmakers continually consider alternatives for achieving future performance goals.

For more information see the Performance-Based Planning and Programming Guidebook.

Transportation Planning Data and Analysis Methods

To initiate transportation plans, State DOTs and MPOs obtain data and analyze it using the travel demand model and other tools to identify future transportation trends, issues, challenges, and needs. The most common data sources and analysis tools are discussed below.

Types of Planning Data

The Census Transportation Planning Products (CTPP) are based on data from the American Commuter Survey (ACS), which is designed to help transportation planners understand commuter information (e.g., where people are commuting to and from and how they get there). The data are used to inform the travel demand model to forecast future travel trends and decisions regarding infrastructure investments. The ACS data are organized by where workers live (residence geography tables), where they work (workplace geography tables), and by the flow between those places (residence to workplace flow geography tables). (ACS data for 2012 to 2016 will soon be released and replace the 2006-2010 data.)

The United States Census Bureau collects quality data about the Nation’s people and economy that can be used by transportation planners for the travel demand model or qualitative assessment. Population, employment, income and poverty, education, health, and housing information, all collected through the Census, inform future transportation investments. The four primary methods for accessing Census Bureau data include: 1) the American FactFinder Web site; 2) DataFerrett (Ferrett stands for Federated Electronic Research, Review, Extraction, and Tabulation Tool); 3) the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) download system; and 4) Census application program interface (API).

The National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) provides comprehensive data on travel and transportation patterns in the United States. The data include information on trip purpose, transportation means, travel time, time of day and day of week, number of people in the vehicle, driver characteristics, and vehicle attributes for private vehicle trips. Planners utilize the data to quantify travel behavior and understand travel patterns to inform future infrastructure needs. State DOTs and MPOs also typically conduct household travel surveys to obtain specific information for the State or region.

Traffic count data help planners understand the volume of vehicle travel on highways and roads in a planning area. The data are used to calibrate and validate the travel demand model, show growth trends, and inform decisions about how and where to program future transportation funds.

DOTs and MPOs develop and utilize transit passenger surveys to evaluate the travel patterns and demographics of public transportation users. The information allows planners to consider future transit routes, service changes or cuts, service expansion, and access/egress to services.

In transportation planning, planners use a wide range of data to make informed decisions. Freight data, land use information, economic development, environmental data, historic preservation, recreation and tourism data, and natural resources are examples of the types of data used in the planning process. The FHWA Planning Web site provides information on planning data and other planning resources.

Transportation Planning Methods and Tools

Travel demand modeling is a tool that uses the best available transportation, population, employment, and socioeconomic data to assess existing travel conditions (baseline) and forecast future travel by testing the impacts of projects or sets of projects on expected performance. The model estimates the amount of travel within, into, and out of a specified area, calibrated to actual existing conditions. The transportation network in the model can be modified to include new projects to see how travel patterns, transportation modes utilized, and congestion changes under these new conditions. Another major application of travel demand models is to demonstrate conformity of future transportation investments with air quality emissions levels. State DOTs and MPOs rely on the results of the model and qualitative inputs (e.g., public and stakeholder engagement) to identify future transportation investments.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is another tool that captures, stores, and displays spatial transportation data. Transportation planners can use GIS to show information to devise programs and projects. Some examples of GIS displays include transportation scenario comparisons, crash clusters, bike routes, land uses, planning study areas, functional classifications, and more. GIS gives meaning to short- and long-range transportation plans by providing innovative ways to visualize data.

A tool that could prove useful to transportation planners is The Transportation Planner’s Safety Desk. The Desk Reference provides a summary of how safety can be integrated into the transportation planning process. This reference, a resource providing a range of safety strategies in 22 emphasis areas that may be implemented by or coordinated by transportation planners. The strategies in the document are derived from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program’s (NCHRP) Report 500 Guidance for Implementation of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Strategic Highway Safety Plan that covers the 22 key emphasis areas identified in the AASHTO Strategic Highway Safety Plan, as well as additional sections on collecting and analyzing highway safety data and developing an emphasis area plan. Each emphasis area section provides an overview of the problem, data defining the problem, and descriptions of strategies that are most relevant to planners. When available, crash modification factors are included that can be used to determine the safety performance of specific safety improvements. Each section provides lists of additional resources and best practices, when available.

One of the strengths of transportation planning is looking at a range of issues and the interrelationships and interactions of these issues. There is a number of tools and applications available for the transportation planning areas of travel demand modeling, scenario planning, land use planning, motor vehicle emissions, and other environmental issues. As examples of these tools, PlanWorks is a resource that assists collaborative decisionmaking in the transportation planning and project development process. This resource provides information to improve development, prioritization, and apprise transportation plans and projects. Metropolitan areas and States also have applied tools to evaluate current and predicted future safety performance. Scenario planning has been embraced by many metropolitan areas and States as a way to examine alternative investments and alternative population, employment, and financial forecasts; while many different performance outcomes can be predicted there has been relatively little focus on safety outcomes. The Travel Model Improvement Program (TMIP) provides research, technical assistance, and training to transportation planners at local, regional, and State levels. Information on these tools and other planning resources can be found at the FHWA Planning Web site.

Transportation Funding

Funding for transportation plans and projects come from a variety of sources, including Federal and State Governments, public or private tolls, local district tax assessments, and local government general fund contributions. The Federal Highway Trust Fund and the Mass Transit Account of the Trust Fund provides funds for transportation projects. Funding programs include:

- The National Highway Performance Program.

- The Highway Safety Improvement Program.

- The Surface Transportation Block Grant Program.

- State Planning and Research (SPR).

- Metropolitan Planning (PL).

- Federal Lands Highway programs.

- Federal Transit Grant Programs.

- National Highway Freight Program.

Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act supports transit funding through fiscal year 2020, reauthorizes FTA programs and includes changes to improve mobility, streamline capital project construction and acquisition, and increase the safety of public transportation systems across the country.

The Act’s five years of predictable formula funding enables transit agencies to better manage long-term assets and address the backlog of state of good repair needs. It also includes funding for new competitive grant programs for buses and bus facilities, innovative transportation coordination, workforce training, and public transportation research activities.

States and MPOs also receive Federal funds, established by formula, to support planning studies and report preparation for the transportation planning process, through FHWA’s State Planning and Research Funds and Metropolitan Planning Funds, and through the FTA §5305(d) and §5305(e) programs, which respectively correspond to the metropolitan planning program and Statewide planning and research program. Planning program funds typically make up a large portion of the State or MPO budget for carrying out planning activities and studies and developing transportation plans, such as S/TIPs and other planning documents. Surface Transportation Block Grant Program (STBG) and FTA’s urban and nonurban area formula programs also can be used for developing transportation plans and other planning documents.

Summary

Safety specialists and transportation planners are working toward a common goal, i.e., a safer transportation system with fewer fatalities and serious injuries as the outcome. Many opportunities are available for coordinating the long-range planning process with the SHSP and other safety plans. Both processes require data collection and analysis, identification of alternative investment opportunities, alternatives ranking, and evaluation.

Module 3 explores the strategies and tools safety and transportation planners can use to communicate safety and planning needs, collaborate on safety and transportation plans and programs, and coordinate the objectives and strategies in safety and transportation planning products.

You may need the Adobe® Reader® to view the PDFs on this page.