U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

| < Previous | Table of Content | Next > |

Communities large and small are taking actions in a variety of ways to improve the safety and mobility of pedestrians and bicyclists and are getting great results. The table below provides an overview of 12 different communities and how they are working to make both quick and lasting improvements.

| Formed a coalition | Conducted a walkabout or collected data | Held events to educate, encourage, or engage | Made a plan | Focused on health | Focused on accessibility | Raised money | Promoted policy or engineering changes | Used social media | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban or Large City Examples | |||||||||

| Washington, DC (pg 34) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Philadelphia, PA (pg 45) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Tulsa, OK (pg 40) | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| New Orleans, LA (pg 47) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Suburban or Medium Sized City Examples | |||||||||

| Memphis, TN (pg 42) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Baldwin Park, CA (pg 58) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Brownsville, TX (pg 50) | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Charleston, SC (pg 52) | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Rural or Small Town Examples | |||||||||

| Philadelphia, PA (pg 45) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Philadelphia, PA (pg 45) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Philadelphia, PA (pg 45) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Philadelphia, PA (pg 45) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

Read their success stories to learn what others are doing, how they're doing it, and get inspiration and tips for replicating efforts in your own neighborhood.

Iona Senior Services is a non-proit organization in Washington, DC with one staffed position, two active senior leaders, and multiple community volunteers. For the past several years, Iona staff have partnered with community members to focus on improving the walkability of a four-mile stretch of Connecticut Avenue, a major six-lane commuter route from Maryland into Washington, DC. The route travels through some of the highest concentrations of older adult (65+) residents in the DC region. These older residents mostly live in apartment buildings, retirement homes, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes. Connecticut Avenue is also a major commercial corridor with transit and bus stops and small businesses that rely largely on pedestrian trafic. More than a dozen schools are also located on or within a block of Connecticut Avenue, from pre-schools to Universities, all of which have people of all ages trying to cross Connecticut Avenue during rush hour and non-rush hour trafic.

In past years, Connecticut Avenue has been lined with wreaths marking the deaths of pedestrians, some of whom were older neighbors who were hit attempting to cross the street to access local businesses and healthcare facilities. More than 50 pedestrian crashes occurred on this street in the period from 2000-2006. Many crosswalks were at intersections without trafic lights or at midblock sites leading to bus stops, where drivers rarely yielded to pedestrians attempting to cross. Where trafic lights existed, there was often inadequate time allotted for pedestrian to cross streets safely. Motorist speeds were high, and speed limits and the law requiring drivers to yield to pedestrians in crosswalks were only sporadically enforced. As a result of these concerns, Iona staff and local community members decided to form a community group to help examine the problems on this corridor

Three community members initially came together, including a pedestrian advocate, the coordinator of a local Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program, and the chair of an advisory neighborhood commission (ANC) – a government body established to advise government entities on local issues – who was also the vice president of a neighborhood alliance. These three activists began engaging others, such as neighbors in nearby Chevy Chase and Cleveland Park communities and the Coalition for Smarter Growth, to support efforts to improve the environment and safety for pedestrians along Connecticut Avenue. They also reached out to the Pedestrian Coordinator of the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) to learn about what efforts were already underway

Three community members initially came together, including a pedestrian advocate, the coordinator of a local Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program, and the chair of an advisory neighborhood commission (ANC) – a government body established to advise government entities on local issues – who was also the vice president of a neighborhood alliance. These three activists began engaging others, such as neighbors in nearby Chevy Chase and Cleveland Park communities and the Coalition for Smarter Growth, to support efforts to improve the environment and safety for pedestrians along Connecticut Avenue. They also reached out to the Pedestrian Coordinator of the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) to learn about what efforts were already underway

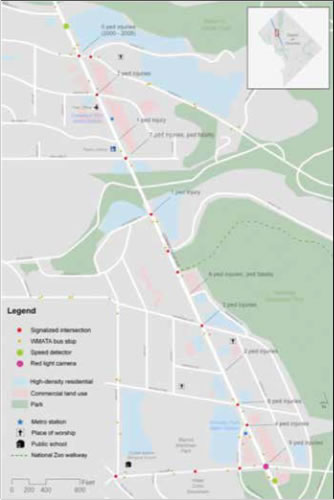

Figure 1. Map of Pedestrian Crashes and Other Key

The group raised $34,080 from local donations and in-kind contributions, including funds provided by the local ANCs, Citizen Associations, the Family Foundation, individuals, and the DC A ARP. The group received in-kind donations for the graphic design and printing of a brochure, free use of meeting rooms for training sessions with audit volunteers, and food from local restaurants for a kickoff event. Raised funds were used to support outreach to the community (such as printing signs and brochures), and to hire a consultant. The consultant, from a local planning and design irm, helped the group develop a customized pedestrian safety assessment tool, train volunteers to conduct walkability assessments using the tool, and create a temporary website which was used to conduct an online survey and host an interactive map community members could use to log concerns about Connecticut Avenue.

The CAPA steering committee recruited and trained more than 80 volunteers to perform audits along Connecticut Avenue (including 23 blocks and 39 intersections) and collect, enter, and summarize pedestrian safety concerns identiied during the audits (see Figure 1). They also conducted three focus groups at senior residential communities, to hear community members' concerns about pedestrian safety in the area. Using the data gathered from the audits, focus groups, and online-surveys, the group developed a pedestrian safety plan for the corridor. The plan highlighted key concerns, made the case for pedestrian safety improvements, and presented a uniied community vision for the changes the coalition wanted to see.

Group leaders presented their plan's recommendations to neighbors in community meetings, to council members, and to DDOT. They coordinated with DDOT to incorporate the recommendations of their plan into an ongoing planning effort, the Rock Creek West Livability Study, which was being led by DDOT. They were also successful in engaging with the local media to highlight their work and plan, including getting a positive editorial, two new articles, and an op-ed in a local newspaper, "The Current."

To date, the group meets monthly to move the CAPA plan forward and to advocate for funding from DDOT, the DC Council, and MPD to implement the recommended improvements and engage in an effective public education program to address pedestrian safety. They continue to collaborate with the MPD for the enforcement component of the effort, in part by adding a member of the police force to the CAPA steering committee.

The information above was provided by Marlene Berlin, former staff member with Iona Senior Services.

North Carolina Route 12 (NC 12) is a two-lane road that passes through the Town of Duck, a seaside resort village on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Duck is home to approximately 500 permanent residents. However, during the summer peak vacation season, Duck hosts more than 25,000 people. During tourist season, there is a signiicant volume of vehicle, pedestrian, and bicycle trafic. NC 12 also serves as a commuter route, providing access to Corolla (north of Duck) and to Nags Head and Manteo (south of Duck). Currently, all trafic coming from or going to Corolla must pass through Duck, since the only bridge crossing (Wright Memorial Bridge) is located to the south of town.

Pedestrians were having dificulty crossing the busy two-lane highway, which was lined with both businesses and residential property. There were designated crossings in the town, but there were not always crossings in the most convenient locations to where pedestrians or bicyclists wanted to go. Furthermore, there were many conlicts between motor vehicles accessing the driveways and side streets and the numerous pedestrians and cyclists walking or riding on the shoulder. There were also conlicts on the shoulder among pedestrians and cyclists.

The town began working with the community to ind out more about where bicyclists and pedestrians were coming from and where they wanted to go, to help make decisions on crosswalk placement. This included talking with committee members working on a Comprehensive Pedestrian Plan, business owners, residents, and elected and appointed oficials. In addition to providing information to support the development of the Comprehensive Pedestrian Plan, the effort helped generate interest in and support for the plan.

In August 2009, town volunteers helped count pedestrians and bicyclists traveling on Route 12. The road was divided into ten, 200-300 foot long zones (see Figure 2). One person was assigned to each zone to count pedestrians and cyclists entering, exiting, or crossing the road within each zone in 15-minute intervals for a two-hour period. One observer could see and accurately record all pedestrian and bicycle activity in each zone. Combined, the six zones extended the entire length of the rural village and captured the areas of highest pedestrian and bicycle activity. Observers were ield-trained in data collection. Data collection included the following:

Figure 2. Data Collection Zones along NC 12.

The data showed that the highest concentrations of entering and exiting pedestrians and bicyclists in the study area were along the east side of the corridor. The pedestrian and bicycle counts showed that crossings occurred frequently at unmarked locations as well as at marked crosswalks throughout the study area (see Figure 2). While some crossings were used regularly, others were rarely used. Several desired crossing locations were identiied from the count information, and along with town input, were used to identify enhanced crossing treatments. This information was used in conjunction with a road safety audit (RSA) – an assessment of roadway design features by a group of transportation professionals following a formal set of procedures – which resulted in crossing improvements that were made along NC 12 (see Figure 3), and identiication of additional measures to be implemented). The needs identiied in the road safety audit report also led the town to pursue and receive a grant from the North Carolina Department of Transportation (DOT) to fund the development of a pedestrian master plan. The town conducted additional data collection and identiied further needed improvements during master plan development. These improvements were subsequently funded and are in the process of being implemented. The Duck Town Council also recently approved the Comprehensive Pedestrian Plan.

Figure 3: Crossing Improvements Included Pavement

Markings and Signage for Drivers and

Pedestrians at

Crosswalks.

Wabasha is a historic, small, rural community in southeastern Minnesota with a population of around 2,800. Nearby communities, including Kellogg, bring the area population to around 5,000. The city is fortunate to perch between majestic bluffs and the Mississippi River, which contributes to a beautiful environment for active transportation and recreation, but also creates some challenges relating to steep topography in some areas. Wabasha is a thriving town that provides a number of services and basic needs of its residents and tourists. As in many rural communities, though, street designs, dispersed development, and distances between communities diminish the opportunities for accessing schools and businesses by walking or biking. It was widely thought that a car was essential for reliable transportation in the area and, until recently, there had been little emphasis on creating a better environment for walking and biking.

High rates of obesity and low levels of physical activity among the city's population called attention to the need for residents to increase activity levels. Local public health workers, the city, and other partners resolved to address these public health issues. They formed a coalition, Fit City Wabasha (http://bit.ly/15o3nYw) to begin to address these concerns. The coalition was originally composed of staff from Saint Elizabeth's Medical Center, Wabasha County Public Health Department, the City of Wabasha, local business owners, and other volunteers with an interest in promoting a healthy community. Fit City has no separate legal status, stafing, or budget.

The impetus for the community to address walkability concerns in Wabasha was to enhance opportunities for physical activity. Local businesses were also interested in improving walkability for visitors to this historic community. At irst, the view was that hardly anyone walked in Wabasha because developing a walking/biking friendly community just had not seemed to be a priority earlier

Community-led walkability assessments were used as a starting point to engage residents and the City Planning Commission about walkability issues. Data gathered from residents who completed the audits suggested that there was much more walking occurring than realized, including among senior residents and in some areas where walking was unexpected. Although the average audit generated a "pretty good" score, the audits helped to identify safety issues on key roads and neighborhood streets, including a road adjacent to a public park. The auditors identiied instances of incomplete sidewalks, sidewalks that were blocked or in disrepair, and streets that lacked crossing infrastructure.

Subsequently, Fit City's promotions focused on increasing physical activity. Fit City Wabasha hosted a "Walk to Win" 10-week Challenge competition between Wabasha and nearby Lake City (see Figure 4). Nearly 400 Wabasha residents, 14 percent of the town's population, and another 300 Lake City residents participated, logging more than 1 million miles walked altogether. Fit City in partnership with the City Historic Preservation Commission and the Wabasha-Kellogg Chamber of Commerce also unveiled four new historic walking tours in brochure form; these have been distributed at some of the area events and are included in tourist information, including on internet outlets. Saint Elizabeth's Medical Center also hosts a Wabasha Walking Routes brochure, which highlights four different walks for itness (http://bit.ly/1zV07O1).

Figure 4: Community Walking Event in Wabasha, Minnesota.

The Walk to Win challenge and continuing events (such as an annual Fit City Kids' Triathlon), the audits, and the walking brochures have generated visibility and increased attention to walkability issues in the community. There is increased collaboration, discussion, and actions among City commissions and varied City departments including planning, transportation, law enforcement, and health. There is also more engagement with the County and other nearby cities.

The City Planning Commission began work on a subdivision ordinance that will help to make new developments, and the Town overall, more walkable. A Complete Streets type of policy statement has also been drafted to include in the new ordinance. A new law enforcement focus on pedestrian safety is also underway. Additional funding was obtained from a Statewide Health Initiative Program to help promote non-motorized transportation by marking and signing a bike route and share the road banners, to mark portions of a ive-mile multi-use trail, and to conduct other outreach activities.

The information above was adapted from a report, Encouraging Physical Activity and Safe Walking in Wabasha, MN, by Molly Patterson-Lundgren, a planner contracted by the City of Wabasha planning department.

The Pearl District neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma is located directly east of the downtown central business district and one mile west of the University of Tulsa. Historically, the area was known for its mix of industrial and residential uses, but had the basic structure of a walkable, urban neighborhood. In recent years, significant redevelopment and a resurgence of interest among residents and business owners has revived the urban fabric of the neighborhood. The Pearl District represents significant potential for pedestrian activity in central Tulsa. In 2005, the neighborhood adopted the 6th Street Infill Plan (http://bit.ly/1pDAaLL), intended to guide the further redevelopment of the area. One of the principal tenets of the Infill Plan is pedestrian orientation. The Infill Plan aims to reduce automobile dependency through increased transit use and to provide bicycle and pedestrian facilities. A sizeable population of residents with physical disabilities lives adjacent to the Pearl District, and this population receives services by the Center for Individuals with Physical Challenges (the Center). The Hillcrest Hospital complex is also just two blocks south and attracts many pedestrian trips.

In a recent year, one-third of all traffic fatalities in the city were pedestrians, and pedestrian fatalities are approaching the number of homicides in the city. Pedestrian safety is a major concern for the Pearl District area, especially as it begins redevelopment and as walking becomes more common. With an active freight railroad running through the area as well, pedestrian safety is a priority. The poor physical condition of existing sidewalks and lack of connected facilities presents safety and accessibility concerns and detracted from pedestrian activity. The City of Tulsa has a reporting system and a ranking system for needed repairs or sidewalk additions, but the system is not easily accessible or transparent for citizens.

As reported in Tulsa People (http://bit.ly/1uCQLRZ), a local store owner became concerned watching residents attempting to navigate Utica Street to the Center and other destinations. She watched pedestrians struggle through the grass: "The baby strollers wouldn't roll, the wheelchairs would get stuck, the journey was exhausting." For the residents of Murdock Villa, an apartment building serving people with physical challenges, it was not only exhausting and inconvenient, but also unsafe and limiting. According to the executive director of the Center, which provides support services to help individuals with physical challenges maintain independence, "For the approximately 40,000 Tulsans with disabilities, sidewalks are often the deciding factor in whether they can go to the grocery store, get a haircut, attend classes, and have freedom."

A group began meeting to focus attention on the needs of disabled residents, especially on the need for sidewalks along Utica Street, across from the Center. During these meetings between representatives from the Pearl District Association and the Indian Nations Council of Governments (INCOG), it became apparent that there was a need for better grass-roots advocacy for pedestrian accessibility. INCOG provides local and regional planning, information, coordination, implementation, and management services to Tulsa metropolitan area member governments.

From the early meetings, the Pearl District Association, The Center, and INCOG launched the Alliance for an Accessible City (Alliance) to advocate for pedestrian improvements. The mission for this group was to "be Tulsa's leading grass-roots advocacy group for safe, accessible, attractive sidewalks." Beginning in November 2010, the Alliance met monthly to discuss strateg y and invited City of Tulsa Public Works leadership to take part in those meetings. Using funding from a small grant, INCOG created a temporary website, which was used to convey information about trafic calming strategies, ways to contact local oficials about pedestrian safety issues, and recruit new members for the Alliance

Some of the early successes of the Alliance were the sidewalks that were, in fact, installed along Utica Street, across from the Center for Individuals with Physical Challenges (see Figure 5). This was the Alliance's first victory and led to a more concerted effort to advocate for sidewalks in other parts of the city. However, this effort evolved into new forms. The leaders of the initial coalition proved to be focused on the particular goal for sidewalks leading to the Center, and once that success was achieved, the Alliance lost momentum. However, many of the people involved in the initial Alliance became members of a new citywide Accessible Transportation Coalition (ATC). This group was fostered by an INCOG mobility manager with a strong personal interest in accessible transportation and access to transit.

The new ATC attracted the attention of the Tulsa County Wellness Partnership (http://bit.ly/1thbSKb), an outreach arm of the Tulsa County Health Department. The Wellness Partnership has many community health goals, and their aim in partnering with the ATC was to facilitate active travel and lifestyles in the interest of community health and well-being. The Tulsa County Wellness Partnership has funded several initiatives of the ATC, including Sidewalk Stories (http://bit.ly/1pkezOE), a series of personalized videos bringing attention to area access and mobility issues and the benefits of pedestrian improvements. The Wellness Partnership is also sponsoring a "Walk to the Future" summit organized by the ATC. Thus, although the new ATC lacks a formal structure or dedicated funding, they have found a partner that does have resources, and supports the objectives of improving access and walkability for health.

Figure 5: New Sidewalk Along Utica Avenue.

Other momentum was more indirectly spurred by the presence of the original Alliance. Members were tapped to serve on the City's Transportation Advisory Board (an official board), and a Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Board, a board established by a city council member to provide advice and advocacy on pedestrian and bicycle issues. The activities of these boards have led to further bicycle and pedestrian planning efforts and adoption of a Complete Streets resolution by the Tulsa City Council, and the subsequent development of a Complete Streets guide for the city.

The information above was adapted from a report, Fostering Advocacy and Communication in Tulsa, OK, by James Wagner, Senior Transportation Planner, INCOG, and supplemented with information collected through a follow-up interview.

The Livable Memphis program (http://bit.ly/1xYnR5W) is a grassroots program begun in 2006 by the Community Development Council of Greater Memphis (CD Council). Livable Memphis advocates for healthy, vibrant, and economically sustainable communities through the development and redevelopment of neighborhoods. Walkability and bikeability are seen as critical components of a livable neighborhood and city. The organization works by building a shared vision and promoting public policies to further that vision. Livable Memphis represents over 125 neighborhoods from across 32 zip codes across the entire Memphis area. With the first paid staffer brought on in 2008, there are now three full time staff with another hire imminent. The organization engages neighborhood groups on a grassroots level, takes advantage of many partner organizations and dedicated community volunteers for help with events, provides consulting, and carries out direct advocacy.

Long-term neglect of sidewalks and other infrastructure, auto-centric sprawl, low density development, and road design practices that increase exposure risk for pedestrians had led to systemic problems and Memphis being ranked as one of the most dangerous large metropolitan areas (of a million or more residents) for child pedestrians. Driving became the default for many residents due to the impracticality of walking great distances and the barriers to safe pedestrian movement. Some residents were, however, deemed "captive" pedestrians and bicyclists, including those with disabilities and those who do not own cars or are unable to drive. The pedestrian infrastructure that did exist was often crumbling or did not meet accessibility and mobility needs of all types of pedestrians.

In addition, the city sometimes did not follow its own ordinances and other legal obligations that have a direct bearing on pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure and safety. A "perfect storm" for progress formed when the combination of new local vision among elected leaders and residents encountered a bicycling advocate with an interest in policy. The bicyclist noticed that projects planned to be funded with Federal stimulus dollars (American Recovery & Reinvestment Act or ARRA, signed into law in February 2009) did not meet legal requirements for considering the needs of pedestrians and bicyclists. Livable Memphis, bicycle advocates, and other partners brought this information to the attention of the City Council with a letter-writing campaign. The council immediately required that bicycle lanes, which could be implemented without major redesign, be incorporated into all the planned ARR A projects. These actions helped to avoid lost opportunities to improve bicycle infrastructure in those project locations; new curb ramps were also installed with the new projects. However, Memphis' ordinance that required property owners to maintain adjacent sidewalks had not been enforced for decades. Crumbling sidewalks, poor driveway crossings, and other issues created barriers and safety impediments for pedestrians traveling between intersections, and the ARR A projects provided little mobility improvement for pedestrians. Numerous wide, high-volume roadways radiating from the city center also dissected neighborhoods and acted as barriers for residents to access commercial centers, schools, and other neighborhoods. These problems provided other opportunities for concerted action.

Since its inception, Livable Memphis has identified and cultivated effective partnerships wherever they could be found. The volunteer policy guru and cycling advocate became an important ally and resource, and early on, bicycling advocates helped clamor for change. There is now a statewide advocacy organization, Bike Walk Tennessee, and Livable Memphis is a member. Another ally was found in the city's engineering department. A deputy engineer proved to be a receptive audience at a time when others were not necessarily listening, and this relationship was cultivated over time. Now, this person is the city's chief traffic engineer and works well with Livable Memphis and partners. Other partners include the Healthy Memphis Common Table, a public health non-profit that supports many of the same goals of Livable Memphis. These and other diverse stakeholders write letters and show up to Council meetings and other events to advocate for specific policies and solutions to identified problems.

A variety of outreach methods are also used to directly engage community members. MemFix (http://on.f b.me/1CbsjB7) is a fun community event that features neighborhood-based temporary streetscaping and treatments (see Figures 6-7).

Besides in-person events, Livable Memphis uses a number of technologies to educate and rally the community. In conjunction with the Memphis Center of Independent Living and Memphis Regional Design Center, Livable Memphis sponsored narrated video audits of important pedestrian corridors illustrating where those with disabilities and/or in wheelchairs would have issues on local sidewalks. The audit videos were then posted on a YouTube channel, "Barrier Free Memphis," for broader distribution (http://bit.ly/1vKHU7b). A newly launched effort, the Create Memphis initiative, uses ioby, an online tool for people to share and develop ideas (http://bit.ly/1uUqWSk). Recently Livable Memphis completed a locally-tailored walkability audit tool, and is promoting its use through presentations and other actions among the neighborhood groups.

Figure 6: MemFix Event that Created Temporary

Improvements on a Roadway.

Figure 7: MemFix Temporary Intersection Improvements,

Including

Crosswalk Markings and Curb "Bulbouts" to

Provide Safer Spaces for Pedestrians Waiting to Cross.

An early success was getting bicycle lanes incorporated into the planned ARR A-funded projects. A city attorney-led initiative to enforce the sidewalk maintenance ordinance was also making significant progress in getting sidewalks repaired before being challenged by a small but outspoken group. Livable Memphis continues to advocate to Council for enforcement of the maintenance ordinance. Among a number of other accomplishments, Livable Memphis was also successful in promoting the hiring of a Memphis Regional Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator and is a driving force behind the Memphis Complete Streets initiative, successfully advocating for an executive order, and facilitating the creating of a Memphis Complete Streets Design Manual and a Street Regulatory Plan.

The information above was adapted from a report, Advocating for Pedestrian Issues in Memphis, TN, by Sarah Newstok, Livable Memphis Program Manager, and supplemented with information collected through a follow-up interview.

The South of South neighborhood comprises 70 dense, urban blocks of south Philadelphia. Since the 1980s, rehabilitation and renovation of properties and new construction projects have affected most blocks in the neighborhood. Significant private investment in the neighborhood has improved housing conditions and attracted new businesses. Property values have risen by 150 percent in ten years, despite the nationwide economic downturn. These activities have shifted the neighborhood demographics. According to a report by the University of Pennsylvania, many of the neighborhood's newer residents are young families who value the area's walkability. The area is experiencing some pains of its age and evolution, along with opportunities to enhance walkability for all residents.

The South of South Neighborhood Association (SOSNA) is served by one paid staffer and a volunteer board of directors made up of 15 neighbors. The membership theoretically includes all residents in the neighborhood, but most activities are carried out by a core group of around 100 dedicated volunteers. Operational funding is provided through a business tax credit partnership program.

In 2009, SOSNA published the South of South Walkability Plan (http:// bit.ly/11SY khj). The Walkability Plan was the culmination of a yearlong planning effort managed by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission (PCPC), and funded by a Transportation and Community Development Initiative (TCDI) through the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission. The Walkability Plan described the current conditions and outlined planned improvements appropriate for each type of street and intersection throughout the neighborhood. Problems identified in the plan included aging infrastructure and street designs that affect walkability, issues related to the ongoing re-development of the neighborhood, and security issues. Contractors involved in the numerous construction projects underway on almost every block frequently blocked sidewalks with dumpsters for long periods. Other barriers included cars illegally parked, street trees, and light and telephone poles. Aging infrastructure, patchy maintenance, and tree roots had also caused sidewalks in some areas to be uneven or broken. While curb ramps existed in many locations, none were compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which requires streets and public buildings to be accessible.

Street design and enforcement issues included cars parked too close to intersections. Many stop-sign regulated intersections, particularly on one-way streets, were treated by drivers to the "South Philly slide." Drivers roll through these intersections looking only in the expected direction of motor traffic, risking crashes and conflicts with pedestrians or bicyclists coming from the other direction. Few on-street bike facilities also resulted in cyclists regularly using the sidewalks, creating conflicts with pedestrians. Many of these issues required action by the City to improve the infrastructure and implement other suitable treatments, and SOSNA sought to help coordinate actions to get the Walkability Plan implemented.

Some of the problems identified in the Walkability Plan included crime, perceptions of crime, and a lack of pedestrian lighting on most streets. The number one concern of surveyed residents was, however, trash and litter. These issues affected the personal security, comfort, and attractiveness of walking in the neighborhood. To some extent, these types of issues could be addressed creatively at a neighborhood level.

SOSNA created a Pedestrian Advisory Committee (PedAC) to contribute to the Walkability Plan and guide priorities. Thirteen dedicated neighbors formed the core of this new committee. Among the priorities of the PedAC were improving education, awareness, and communication with property owners to address chronic problems including sidewalk obstructions, lack of lighting, and trash dumping. The SOSNA Safety Committee also meets regularly with the Philadelphia police district, and works closely with the TownWatch community initiative. Following some of these activities, the community sought low-cost, practical, and immediate solutions to improve pedestrian-oriented lighting throughout the neighborhood and to address other safety and security issues.

PedAC members thought that the objective of safer nighttime streets could be achieved in the short term by encouraging all neighbors to turn on their stoop lights at night. The initiative was named Lights ON! Southwest Center City. The PedAC applied for and received a donation of more than 500 compact fluorescent light bulbs (CFLs) from the Philadelphia Electric Company, which they distributed through a special event at a local pub. PedAC also created post-it notes (see Figure 8) to distribute door-to-door, especially on some of the neighborhood's darker blocks, to advertise the light give-away event. The bulbs continue to be distributed at police district community meetings and other community safety events.

Figure 8: Pre-printed post it notes used to share

information with neighbors about the Lights ON! Effort.

Another initiative undertaken, SeeClickFix & Philly 311, was intended to make it easier for neighbors to record complaints and report nuisance issues on their block that required City action. Although any resident could do this directly, the SOSNA program coordinator became a neighborhood liaison available to convert the complaints and requests into Philly311 service requests. The SOSNA Clean and Green committee also leads a number of programs designed to make the neighborhood more attractive and environmentally pleasing to its current and potential residents and businesses.

The Lights ON! initiative has led to better nighttime lighting of dark blocks, according to local SOSNA members. Since the SeeClickFix program was initiated, neighbors have identified obstructed or broken sidewalks, illegal trash dumping, and other pedestrian-safety-related issues. New waste receptacles are being installed at strategic neighborhood locations. New recycling programs, Neighborhood Clean-Up Days and other activities also help to create a more pleasant environment.

More recently, SOSNA, and the PedAC have successfully implemented street improvements through a Better Blocks Philly demonstration project (see Figures 9 and 10). For more on the Better Blocks event, visit: http://bit.ly/1yTwk7J.

Figure 9: Temporary Road Diet and Crosswalk

Created

for the Better Blocks Philly Event.

Figure 10: Temporary Traffic Calming Devices

Created

for the Better Blocks Philly Event.

The information above was adapted from a report, Engaging Residents in Pedestrian Safety Issues in Philadelphia, PA, by Andrew Dalzell, former staff member of SOSNA.

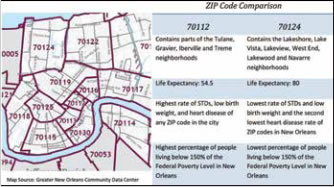

Louisiana consistently ranks among the States in the U.S. with the highest rates of childhood obesity. Within New Orleans, there is a more than 25 year difference in life expectancy between individuals living in the zip code area with the highest socio-economic indicators and those living in the zip code with the lowest indicators (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: 25.5 Year Life Expectancy Difference between

High- and Low-Income Areas in New Orleans.

The KidsWalk Coalition in New Orleans was the brainchild of a former epidemiology professor at Tulane University's Prevention Research Center (PRC). Concerned about childhood obesity and equity issues in New Orleans, she realized that infrastructure improvements were a key to unlocking children's travel mobility and providing options for kids to be active in their travel to school daily journeys and at other times. An initial partnership was formed between the PRC and the City of New Orleans and other public health partners to work on improving infrastructure. One of these partners, the Louisiana Public Health Institute (a statewide nonprofit), funded a traffic engineer from 2003 to 2008 as part of the Steps to a Healthier New Orleans program, which was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This traffic engineer focused on pedestrian and bicycle issues and helped to ensure that Federal funding was leveraged to enhance active transportation and recreational opportunities for the city's children. The engineer was embedded in the city's Department of Public Works. With limited resources for hiring additional staff at the time, the city agreed to this arrangement, whereby the engineer provided technical assistance to the city, but was not an official member of staff.

Then Hurricane Katrina descended on the city in 2005. Following Katrina, a lot of work in progress came to a halt as priorities shifted toward urgent recovery needs. It took a while for the city to regroup; then new visioning processes started up. Residents and city officials thought there was a real opportunity to build on the kind of work that had started before Katrina to make walking and biking "easy" choices in New Orleans.

After the CDC funding ended, ENTERGY, the local energ y provider, committed to provide continued funding for the engineer position with the city. The Tulane PRC, in partnership with the City of New Orleans, also applied for, and received a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) grant through the Healthy Kids, Healthy Communities (HKHC) program, an initiative aimed at reversing the childhood obesity epidemic by 2015. Following the model of providing technical assistance, the partnership used the awarded funds to support a planner to work with the engineer and provide additional expertise to the community. The planner also focused on pedestrian and bicycle issues, SRTS initiatives, and, like the engineer, was embedded with city staff. The KidsWalk Coalition was formed in 2009 from this partnership with a mission to "to reverse the childhood obesity epidemic in New Orleans by making walking and bicycling safe for children and families to access schools, healthy eating choices and other neighborhood destinations." The RWJF HKHC program funded the KidsWalk Coalition activities from 2010 to 2014.

Among the coalition-funded staff objectives were to ensure that Federal Katrina-recovery funds were optimized to make improvements in pedestrian and bicycle facilities and to help coordinate sidewalk improvements with street improvements. The KidsWalk staff provided support and assistance to any school in Orleans Parish wishing to make pedestrian and bicycle safety improvements surrounding their campus. As a liaison between schools and the Department of Public Works, the staff coordinated sign replacements and crosswalk maintenance, they advised on pick-up and drop-off logistics, and on-campus safety improvements. The staff also assisted elementary and middle schools with applications for funding and implementation of Safe Routes to School activities (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: KidsWalk Staff Provided Support to

Schools

Looking to Make SRTS Improvements.

The partnership secured its own SRTS grant to focus on education and encouragement of kids walking and bicycling to school, and to improve enforcement through development of a school crossing-guard program. A new partner, Bike Easy, a local board-led non-profit with a mission to "make bicycle riding in New Orleans easy, safe, and fun," was a natural fit to take charge of the encouragement and education aspects of the State SRTS-funded initiative. Bike Easy is developing a pedestrian and bicycle safety education and encouragement program for fourth and fifth grades that will be piloted at 10 schools.

The original KidsWalk partnerships continue and have expanded to include over 25 active partners including community-based organizations. The following are among the accomplishments of the partnership:

Presently the partnership is seeking to improve outreach to bring more community members and input into on-going efforts.

Information provided by Naomi Doerner at Bike Easy and formerly with the KidsWalk Coalition.

Brownsville is a city of 175,000 residents at the southernmost tip of Texas, sharing a border with Mexico. Ninety-three percent of people in Brownsville are Hispanic and the metro area has one of the highest poverty rates in the country. The community also faces a lot of health disparities – one in three people are diabetic and 80 percent are either obese or overweight, so the driving force of Brownsville's efforts related to walking and biking has been to activate community members to improve their health.

Over the past decade community partnerships have formed to improve public health by encouraging physical activity and promoting healthy eating. In 2001, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health opened the Brownsville Regional Campus, which focuses on obesity-reduction strategies. The school made a concerted effort to become a partner with the community and formed a Community Advisory Board (CAB) comprised of leaders from nonprofits, schools districts, city government, health care, business, and community groups. The CAB helps translate research and provides a forum for community members to voice their opinions on decisions and initiatives related to community health. The CAB started with media campaigns, founded a farmer's market, and supported wellness programs, but lack of physical activity was still a major barrier to improving community health and wellness. To achieve the vision of a healthy and livable community – part of the city's 2009 comprehensive plan – the city needed to commit to filling crucial gaps in the sidewalk network, constructing new bicycle facilities, and providing opportunities that encourage people to be more active.

A couple of forward-thinking city commissioners and the mayor began a call for bike lanes as part of a vision of a more bikeable and physically-active Brownsville. City Commissioner Rose M. Gowen, MD, is adjunct faculty at the Houston School of Public Health and was instrumental in pushing the health angle. The city planning staff conducted community outreach and quickly found that one of the biggest impediments to more physical activity was a lack of safe environments to be active, and thus recognized that improved infrastructure was needed in order to support the goal of having a healthy, active community. Political leadership was also instrumental for the city's adoption of a Safe Passing ordinance (requires drivers to allow at least four feet when passing vulnerable road users), a new ordinance requiring sidewalks for commercial developments, and a Complete Streets policy that was developed following a public workshop.

The city also hosted several events to get community members engaged and involved. For example, thousands of residents attend Brownsville's CicloBia events, where downtown streets are closed to motorized traffic so that residents can walk, bike, run, and play freely (http://www.cyclobiabrownsville.com/). The city has also worked with local businesses to host Build Better Block events where local streets are temporarily turned into pedestrian plazas, but this type of event is now subsumed within the Brownsville CicloBia. The city has hosted at least seven CicloBias, often held in the evenings to avoid the Texas heat, and the participation in these events continues to grow. The Houston School of Public Health regularly surveys CicloBia participants; results find that 69 percent of attendees would have been sedentary if they weren't at CicloBia and that the average participant is physically active for 123 minutes while at the events.

In 2013, Brownsville adopted its first Bicycle and Trail Master Plan that laid out the city's 10-year vision for walking and biking in Brownsville. The city wanted to ensure that all residents had an equal voice in developing the plan, so staff sought new mediums beyond traditional public hearings, which often result in simple information dissemination. At the annual Charro Days Fiesta, the city bought four bikes to raffle off to residents who filled out a survey – they collected nearly 900 surveys that represented the range of demographics. They also partnered with the school district and hosted meetings at four schools, each of which had 50-70 attendees. Following the adoption of the plan, the City continues walking- and biking-related community outreach to garner continuous feedback during the plan's implementation. In the implementing the plan, the city is first implementing rapid-term projects (two-year timeline) that are high-visibility projects that serve the most people (see Figure 13). These types of projects will hopefully lead to continued support from the 97 percent of CicloBia attendees who want more designated bike lanes and the 44 percent of attendees who say that the main barrier to walking and biking more often is their concern about safety.

Figure 13: Brownsville Staff Conducted Outreach and

Bike-on-Bus Trainings after Church on Sundays.

One small example of how the culture is changing in Brownsville is that the City went from having one bike shop to having three. These shops now represent important community partners that promote physical activity by hosting rides and sponsoring events (see Figures 14 and 15).

Figure 14: A Bike Ride on One of the

City's Newest

Shared-Use Paths.

Figure 15: Bicycle Skills Trainings for

Some

of the City's

Youngest Residents.

Important programmatic spin-offs that followed initial efforts from the CAB and the city include the Bike Barn, an all-volunteer-run operation where kids learn how to repair bikes and can eventually earn a bike of their own, and the Bike Brigade, which organizes rides for different abilities and distances (http://on.fb.me/15qorxy).

In summer 2014, Brownsville was named an All- America City by the National Civic League and was one of six winners of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health Prize. These awards are well deserved, but not a sign that the mission is complete, just on the right track.

Information and images provided by Ramiro Gonzalez, Comprehensive Planning Manager at the City of Brownsville.

In 2003, in response to community pressure to improve conditions for bicyclists and pedestrians in and near Charleston, South Carolina, the Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Council of Governments (BCDCOG) – the region's metropolitan planning organization – submitted a successful proposal for funding to the RWJF Active Living by Design Program. The $200,000 grant funded the creation of a regional bicycle and pedestrian action plan as well as a partnership to promote health and active living.

The partnership included a bicycle and pedestrian advocacy group, the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, the South Carolina Department of Transportation, the Medical University of South Carolina, and several healthcare organizations. The action plan contained three main goals: 1) to implement a Safe Routes to School program, 2) to implement Complete Streets policies to make roads accessible for all users, and 3) to begin community intervention programs to improve bicycling and walking conditions.

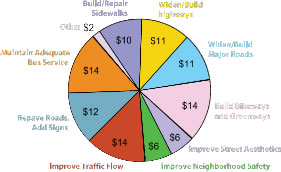

Figure 16: Results of Resident's Poll Regarding

Transportation Spending Priorities.

The community was involved during the planning process. During the creation of the long-range transportation plan, the BCDCOG distributed a survey asking local residents how much they would spend on different transportation infrastructure elements if given just $100. On average, respondents allocated $24 for pedestrian and bicycle improvements, which contrasted with the existing allocation of $0.05 for pedestrians and bicycles out of every $100 spent (see Figure 16).

The agency took steps towards narrowing this discrepancy by allocating $30 million for pedestrian and bicycle improvements over the next 21 years. For more information, visit the BCDCOG website at http://www.bcdcog.com/. Mobilizing Community Leaders and Volunteers for Safe Routes to School Programs Corrales, New Mexico

Corrales is a rural village in northeastern New Mexico. Nestled into a bend on the west side of the Rio Grande, this agricultural community of just over 8,000 people within 11 square miles is hemmed in by Albuquerque to the south and sprawling Rio Rancho to the west and north. Most traffic in the village is funneled onto one road that provides access to all three of the village's schools: Sandia Elementary on the north side of the village, Corrales Elementary in the center, and Cottonwood Montessori on the south side. As a result, the town experienced severe traffic related to elementary school student drop-offs and pickups. Upwards of 250 vehicles arrived at Corrales Elementary each day, which over whelmed the school zone, blocked the shoulder for pedestrians, blocked the road for through traffic, blocked neighbors' driveways, and led to prohibited pickups and drop-offs in the parking lots of nearby businesses. The congestion also led to numerous traffic violations by other drivers including speeding on side roads, passing on the shoulder, and failure to stop at stop signs and crosswalks. Drivers using side roads near the school to avoid traffic on Corrales Road nearly collided with walking children on several occasions. More than 200 students lived within a mile of school, making them ineligible for bus transportation. But their parents didn't feel like the streets were safe enough for their children to walk or bike; less than five percent of them – about 25 kids – did, contributing to the cycle of more vehicles on the roads.

Walking and cycling advocates on the Town's Bicycle-Pedestrian Advisory Commission (CBPAC) were aware of these travel challenges, and they sent student travel surveys home with all 564 Corrales Elementary students in November 2004. Half of the surveys were returned, with many parents writing passionately about the concerns they had for their children's safety. In April 2005, the town held a community meeting to address this issue, and in 2006, Corrales participated in National Walk to School Day. At least 130 Corrales Elementary and Cottonwood Montessori students participated, and the event organizers built upon the momentum of this program by making Walk- N-Roll to School a monthly event. Parents and local advocates, and even the Mayor, served as volunteers for monthly bike and walk to school events (see Figures 17 and 18).

Figure 17: Students Walking to School along the Acequias.

Figure 18: Walk-N-Roll Volunteers, Including Mayor Phil

Gasteyer (left).

Event organizers were concerned with finding the safest possible routes to school and found it in a community asset – the acequias. Acequias are irrigation ditches brought to New Mexico by Spanish settlers more than 400 years ago, and they carry water for crops. The sides of the acequias, known as ditch banks, provide paths for nonmotorized travel. The use of the acequias for SRTS rekindled a long-standing but dormant effort to develop a Trails Master Plan for the community. That plan has since been completed and accepted by the Village Council, with SRTS an integral component.

In 2007, the Village Council completed a successful proposal to earn Corrales' first SRTS funding, $15,000 to develop a Safe Routes to School Action Plan. For its first step, the Village Council appointed a SRTS Committee that collaborated with school principals to set a schedule of monthly walk and bike to school days throughout the school year. Walk-N-Roll to School Day continued for several years while SRTS planning in the village stayed on track.

In 2010, following the completion of an Action Plan, the Committee submitted a request for SRTS infrastructure funding and separate funding for educational and encouragement activities. The $25,000 non-infrastructure grant was approved, and the STRS committee used the funds to hire a coordinator. Hired for just the 2011-12 school year, the coordinator's tenure marked an explosion in SRTS activity in Corrales. During this time, Walk- N-Roll increased from a monthly program to one that occurred three times each week. Accelerating from once a month to three times a week wasn't a totally smooth transition. Gradual change allowed parents and school staff to adjust their routine, and once people felt ownership of the program, it expanded dramatically.

Along with the expansion came the need for volunteers to lead the walks and bike rides with children and provide supervision. This included not just parents, but older, retired residents as well. Kiwanis Club members are very active in Corrales and trusted by their community, and many Kiwanis were eager to volunteer. They volunteered regularly and were key participants to expanding the program. The expansion also included outreach to local businesses, which began donating incentives and coupons to students who walk and bike to school. Students were able to track their walking and biking on punch cards to earn points toward incentives like passes to the local swimming pool and movie theater.

Funding for the position expired after the 201112 school year, by which time approximately 25 percent of Corrales Elementary students were walking and biking to school on a regular basis. While the program has slowed a little since – the Wednesday afterschool Walk-N-Roll has been cut – walking and biking participation is still growing, with up to 29 percent of students walking in early 2013, including on non-Walk-N-Roll days. The program's success caught the attention of the National Center for Safe Routes to School, and Corrales received special recognition as a recipient of the 2012 James L. Oberstar Safe Routes to School Award. This accolade recognizes successful SRTS programs, and is awarded annually by a multi-organization panel of reviewers coordinated by the National Center.

The information above was adapted from the article, New Mexico Village Finds Safe Routes, Sense of Community Along by the National Center for Safe Routes to School in April 2013. http://bit.ly/1xYvVnl

Newport, Rhode Island, is a small picturesque colonial town. Located on Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay, Newport is surrounded by the sea. With historic houses dating to the early 1700s, majestic mansions, miles of seaside paths and beaches, and some of the world's best sailing, New por t is a popular destination for holidays and recreation. The population of 24,000 can swell to 100,000 in the peak summer season. With only 11 square miles, most destinations in the city are within walking or biking dist ance.

With the visitors come the traffic congestion and parking challenges that can strain a city and its fragile historic landscapes. In addition, there are few alternatives to driving; just a few years ago, there was not a single bike path or protected lane on Aquidneck Island. By city ordinance, bicycle riders over the age of 13 must ride on the roads with the traffic. In Newport, this created concerns with bicyclists and vehicles sharing narrow one-way streets; bicyclists risking falls on old, uneven surfaces; and distracted tourists cruising the boulevards.

Bike Newport, the local bicycle advocacy organization, seeks to improve, encourage, and facilitate bicycling in Newport. The organization plays a key role in connecting all of the stakeholders working toward road user safety, including:

Bike Newport played a key role in assembling stakeholders to participate in the Rhode Island Department of Transportation's (RIDOT) first ever Vulnerable Road User Safety Action Plan. This plan provided an approach for addressing the safety needs of vulnerable road users – pedestrians and bicyclists – in the City of Newport. Bike Newport, through their efforts in working with the community and other stakeholders, helped bring to the table key participants who were actively engaged in identifying issues and formulating strategies to address these issues. Bike Newport staff led the team in a review of existing bicycle facilities, which was critical in demonstrating challenges. The plan now serves as RIDOT's municipal model for addressing pedestrian and bicycle safety.

In addition to working collaboratively with RIDOT to provide input on local bicycle plans, Bike Newport spearheads a number of other initiatives:

Figure 19: Bike Newport Staff Engage with Local

Enforcement and Other Agency Staff on a Range of

Bicycle Issues,

Including Efforts to Prevent Bike Theft.

Figure 20: One of Newport's Newest Bike Lanes.

As a result of the group's involvement in the plan and other efforts, Bike Newport is one of the first organizations contacted for other efforts conducted by RIDOT, such as participating in safety reviews and evaluations of roads regarding the suitability for bicycles. Additionally, bike lanes and shared lane markings have been added to many Newport streets, thanks to in large part to Bike Newport's efforts working with State, city, and other stakeholders (see Figure 20).

In 2013, Newport was recognized by the League of American Bicyclists (LAB) as a Bicycle Friendly Community at the bronze level – the first in Rhode Island. Nicole Wynand, Director of LAB's Bicycle Friendly America program, said, "We were very impressed by how far Newport has come in such a short period of time. This is a great example how a strong local advocacy group can make a real difference." The city and Bike Newport continue working to move up that scale, in the interest of all of the city's residents, workers, and visitors.

Baldwin Park is a city of 79,000 residents located in the central San Gabriel Valley, 15 miles east of Los Angeles County, California. Compared to other communities within the region and state, Baldwin Park is particularly disadvantaged, with many residents facing socioeconomic burdens. As a result, health burdens follow. Baldwin Park has a large number of drive-through restaurants, which signify the auto-oriented design of the community and its lack of emphasis on physical activity. The community is crisscrossed by a series of major thoroughfares with high traffic speeds, and is missing sidewalks and bicycle lanes that make it difficult to walk or ride a bike to the city's Metrolink regional passenger rail station, 20 public schools, and other destinations. There is limited green space per capita, and high levels of congestion contribute to poor air quality.

Aware of the challenges facing the community, Baldwin Park started early in its efforts to improve local health. The city began passing policies in ordinances as early as 2003 to address obesity and the lack of walkability within Baldwin Park. In addition, Baldwin Park is predominantly Hispanic (80 percent), and therefore home to a large Spanish-speaking population who need tailored outreach to be engaged in the local initiatives to improve health.

The California Center for Public Health Advocacy (CCPHA) developed a model for community engagement to promote health within Baldwin Park. CCPHA helped the city develop People on the Move (POTM), made up of the 57th Assembly District Grassroots Team in Baldwin Park. POTM is a program funded through the California Endowment's Healthy Eating, Active Communities (HEAC) initiative. POTM's primary goal is "to reduce disparities in obesity and diabetes among school-aged children by improving the food and physical environment in Baldwin Park". To do this, CCPHA and POTM developed a system of shared leadership; this involved bringing community members in contact with various sectors and agencies, including the County of Los Angeles Department of Health Services, Kaiser Permanente, Citrus Valley Health Partners, Baldwin Park Unified School District, and Search to Involve Pilipino Americans (a nonprofit organization aimed at improving health outcomes for Pilipino residents in the Los Angeles area).

POTM developed and hosted "Change Starts with Me", a six-week advocacy boot camp to train local advocates to take action to support health and physical activity. Participants for this program were chosen strategically from the community, and were recruited through community events, including health fairs, city council meetings, community forums, and concerts in the park. POTM also sought local advocates through targeted recruitment through partner organization contacts, such as preschool and childcare organizations and reaching out to identified community leaders. Through this recruitment strateg y, "Change Starts with Me" participants included representatives from traditional partners within the region, such as city departments, school districts, and the Mexican American Opportunity Fund (the largest Latino-oriented family services organization in the U.S., which serves disadvantaged individuals and families in the Los Angeles Area). However, this also led to collaboration with nontraditional partners, such as Cal Safe, a school-based program for expectant and parenting students and their children; local women's clubs; the City of La Puente Little League; and the East Valley Boys and Girls Club.

During the camp, participants identified decision- makers and allies, and they gathered data and tools to help document their community concerns (see Figure 21). Upon completion of the advocate training, residents were ready to participate in advocacy efforts, evaluate and speak about the built environment, and have a foundation of knowledge regarding health and nutrition. The comprehensive and targeted recruitment strateg y led to training advocates deeply rooted in the local community. "Change Starts with Me" shifted the ownership of the healthy communities initiative from the CCHPA, the statewide organization, to the local advocates.

Figure 21: Community Members Participate in Advocacy

Leadership Boot Camp, "Change Starts with Me."

Key community advocates formed the Baldwin Park Resident Advisory Council, in which members participated in the planning of community activities and actions to change systems and local policies to support parents in leading healthier lives and having a voice in their community. They worked to develop several programs to engage teens and youth in advocating for safer streets and healthier food options. Two organizations, Healthy Teens on the Move and Kids on the Move, used teen and child-led efforts to improve youth visibility and youth testimony on how the environment impacts young people's choices to be active and eat healthy (see Figure 22).

Figure 22: Community and Youth Engagement to

Support Bicycling for Health.

In 2009, the City organized the SMART (an acronym for Safe Mobility And Reliable Transit) Streets Task Force, which included a successful series of community workshops to evaluate the walkability of Baldwin Park. Conducted in English and Spanish, these workshops represented a variety of interests, including schools, businesses, residents, and high-school students.

The city hosted a Complete Streets Community Charrette; more than 500 residents participated in a three day Design Fair with the city, CCPHA, and transportation experts to develop and adopt a plan for improving pedestrian access and walkability. It included educational workshops, focus groups, and walkability assessments. Based on all of the input received from community members and leaders and during site visits, the project team then developed an initial set of recommendations. These results were shared with city staff and honed for presentation at the charrette's closing event a few nights later. The closing event featured dinner and a mariachi concert at City Hall, where the project team made a presentation, in English and Spanish, to 125 elected officials, city staff, residents, and other community leaders. They reviewed key findings from the community input, and shared the team's recommendations, including visuals of potential changes.

The city was able to hire a full-time employee dedicated to analyzing the intersection of health and the built environment, and this staff member conducted community engagement, evaluated city corridors, and developed the proposed Complete Streets policy for Baldwin Park. The position was funded through the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Developing the Complete Streets policy was a community effort. In addition to the design charrette, POTM hosted six community meetings to discuss the issues, many of which were led by Spanish speakers.

The local initiatives and partnerships have paid off. Through an Annual Fitness Test, the Baldwin Park Unified School District measured a 13 percent decrease in Body Mass Index in students from 2004-2009.

In July 2011, Baldwin Park adopted a Complete Streets policy. This was not only the first policy of its kind in southern California at the time, but was also recognized by the National Complete Streets Coalition as "one of the strongest Complete Streets policies in the nation." Upon passing this policy, the city established an inter-departmental advisory group to oversee implementation, including members from the Departments of Public Works, Community Development, Recreation and Community Services, and the Police Departments.

In 2012, Baldwin Park received a grant from the California DOT to improve pedestrian and bicycle safety for students. A total of $235,000 was awarded to improve its current SRTS Plan, with a provision to increase bicycle and pedestrian safety. This plan seeks to concentrate pedestrian student traffic onto designated routes, and to provide better security for students walking to and from school. The plan was developed with input from neighborhood advisory groups, school district staff, local trained advocates, city staff, and parents. Implementation of the plan is ongoing.

Information and images provided by Alfred Mata, Local Policy Associate with the California Center for Public Health Advocacy. For more info, visit: http://bit.ly/1xBu6ra and http://bit.ly/1AQ0D3e.

| < Previous | Table of Content | Next > |