U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

| < Previous | Table of Content | Next > |

Traditional Neighborhood Design (TND) (also called "New Urbanism" and "Neo-Traditional Neighborhood Design") is a town planning principle that has gained acceptance in recent years as being one solution to a variety of problems in suburban communities throughout the country. Traditional neighborhoods are more compact communities designed to encourage bicycling and walking for short trips by providing destinations close to home and work, and by providing sidewalks and a pleasant environment for walking and biking. These neighborhoods are reminiscent of 18th and 19th century American and European towns, along with modern considerations for the automobile.

This lesson includes an informative article on TND/New Urbanism that appeared in the May 1994 edition of Engineering News Record . It is written from an engineering perspective, but it also describes the cooperative spirit that must exist between planners, architects, and engineers to make TND work.

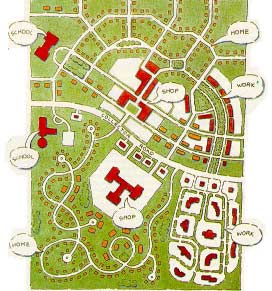

![Village model showing gridded streets and clustered buildings of different types proposed for Haymount [Virginia] development. (Photo and caption, ENR, May 9,1994.)](images/06_01_0001.jpg) Village model showing gridded streets and clustered buildings of different types proposed for Haymount [Virginia] development. (Photo and caption, ENR , May 9, 1994.) |

Engineering News Record article, May 1994. Reprinted with permission. New urbanists are zealots. They proselytize their antidote to alienation – new old-style towns – with a missionary's fervor. And after a frustrating first decade bucking an automobile-driven society unfriendly to their peripatetic ways, they are beginning to make great strides.

With several neo-traditional neighborhoods built, public planners are taking notice. Some are even adjusting general plans and zoning for compact walkable mixed-use towns. Suburban traffic engineers and public works officials are no longer simply recoiling at the prospect of pedestrian-friendly street patterns with narrower, gridded and tree-lined streets. And market surveys are convincing skeptics that suburban residents are content living in a town that by design nurtures both community consciousness and the individual spirit.

"Contemporary suburbanism isolates and separates," says Paul Murrain, an urban planner based in Oxford, U.K. Consumers are recognizing "in their hearts" the better quality of life offered by new urbanism, he adds.

Though new urbanism is also intended for cities cut to pieces by highways, it is more the planner's answer to suburban sprawl and the breakdown of community caused by a post-World War II obsession with the automobile. Apart from nearly total dependence on the car, the typical suburb, with its looping or dendritic street pattern and dead-end cul-de-sacs, "is laid out so that it can't grow," says Andres Duany, partner in Andres Duany & Elizabeth Plater- Zyberk Architects and Planners (DPZ), Miami. "It chokes on itself in very short order."

New urbanism allows travel from one destination to another without using collector roads. (Photo and caption, ENR , May 9,1994.) |

"Suburban sprawl is riddled with flaws," Duany continues. Unfortunately, "all of the professions [involved in development] have sprawl as their model."

Even those who do not subscribe to new urbanism see a need for change. "We are finally recognizing we should plan communities, not structures," says Carolyn Dekle, executive director of the South Florida Regional Planning Council, Hollywood.

"New urbanism is a return to romantic ideas of the past and does not respond to current lifestyles," says Barry Berkus, principal of two California firms, B3 Architects, Santa Barbara, and EBG Architects, Irvine. "But it is part of a knee-jerk, but needed, reaction to irresponsible planning that produced monolithic neighborhoods without character."

Duany, both charismatic and outspoken, and his cerebral wife Plater-Zyberk are in new urbanism's high priesthood. To focus attention on their goals, DPZ and several others created the Congress for the New Urbanism last year. The second meeting is set for May 20 to 23 in Los Angeles. "We need all the converts we can get," says Duany, because, "inadvertently, one thing after another prevents it." Among these are fear of change and criticism that the new urbanism model is too rigid - robbing the individual residents of choice.

Regardless of criticism, converts are beginning to spill out of the woodwork. "Before my conversion, I was a schlock developer," confesses John A. Clark, of the Washington, DC, company that bears his name. "Most of my stuff was so bad it makes your teeth ache."

Then in 1988, after reading about neo-traditional development, the movement's original name, "the light bulb went off," says Clark. He called Duany and soon enlisted DPZ in the campaign for Virginia's Haymount.

There are other tales of conversion. "We were Duanied," says Karen Gavrilovic, principal planner in the Loudoun County Planning Dept., Leesburg, VA. Last year, the county adopted a comprehensive general plan based on new urbanism, which just won an American Planning Association award.

Until new urbanism becomes mainstream, the approvals process for each community tends to be tortuous and therefore expensive. "The thing that must change is the cost of establishing new communities," says Daniel L. Slone, a lawyer with Haymount's counsel, McGuire Woods Battle & Boothe, Richmond. "It will take the cooperation and leadership of planners, politicians, and environmental and social activists."

Approvals are complicated. The approach "raises hundreds of landuse questions" that must be answered, says Michael A. Finchum, who as Caroline County's director of planning and community development, Bowling Green, VA, is involved with Haymount.

"Anything new is of concern," especially to lenders and marketers, agrees Douglas J. Gardner, project manager for developer McGuire Thomas Partners' Playa Vista, a new urbanism infill plan sited at an old airstrip in Los Angeles ( ENR, 10/04/93, p. 21). But Gardner sees planning obstacles as surmountable and blames Playa Vista's 5-year approval time on a trend toward a "more rigorous regulatory framework" for all types of developments.

New urbanism combines aspects of 18th and 19th century American and European towns with modern considerations, including the car. As in Loudoun County, the model can be applied on any scale – to a city, a village, or even a hamlet. In West Palm Beach, FL, which is drafting a new urbanist downtown plan, it is superimposed on an existing urban fabric. Though most of the architecture so far has been traditional, any vernacular is possible.

Like a bubble diagram, neighborhoods should overlap at their edges to form larger developed areas, interconnected by streets, public transit, and bicycle and footpaths. Regional mass transit and superhighways enable workers to commute to remote job centers.

Superhighways-Have they done more harm than good? |

To make new urbanism work on a wider scale, San Francisco-based Calthorpe Associates promotes urban growth boundaries and future development around regional transit. But localities are afraid they will lose control, so most States have not authorized regional governance, says Peter A. Calthorpe. The result is "fractured development, no regional transit, and no attention to broader environmental and economic issues," he says.

There are many proposed new urbanism projects, but less than a dozen are built. Most, not yet 5 years old, have yet to reach build-out. The more well known are DPZ's Kentlands in Gaithersburg, MD; architectplanner Calthorpe's Laguna West in Sacramento; architect Looney Hicks Kiss' Harbor Town in Memphis; and DPZ's Seaside, a northern Florida vacation-home town.

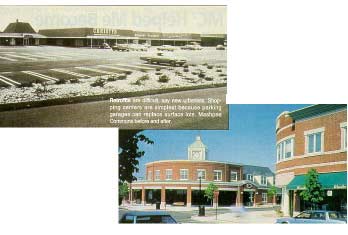

Retrofits are possible, but more difficult. Subdivisions, with multiple landowners and streets that are nearly impossible to link, are the most troublesome. Office park and shopping center makeovers, such as Mashpee Commons on Cape Cod, are easier because the cost of a parking garage to free up surface lot space for development can often be financially justified, says Duany.

The optimal new urbanism unit is 160 acres. Typically, the developer provides the infrastructure. The town architect establishes and oversees the plan and designs some structures. But other architects are also involved. Public buildings and space, including a community green, are located near the center, as are many commercial buildings.

| Street Design | Standard | New Urbanism |

|---|---|---|

| Basic layout | Dendritic | Interconnected grid |

| Alleys | Often Discouraged | Encouraged |

| Design speed | Typically 25-30 mph | Typically 20 mph |

| Street width | Generally wider | Generally narrower |

| Curb radii | Selected to ensure in-lane turning | Selected for pedestrian crossing times and vehicle types |

| Intersection geometry | Designed for efficiency, safety, vehicular speed | Designed to discourage through traffic, for safety |

| Tree, landscaping | Stricly controlled | Encouraged |

| Street lights | Fewer, tall, efficient luminaires | More, shorter, closely spaced lamps |

| Sidewalks | 4-ft minimum width, outside right of way or to indulate | 5-ft minimum, within ROW and parallel to street |

| Building setbacks | 15 ft or more | No minimum |

| Parking | Off-street preferred | On-street encouraged |

| Trip generation | Developed from a sum of the users | Developed from a reduced need for vehicular trips |

ENR , May 9, 1994.

Under new urbanism, there is often no minimum building setback. Lot widths are typically multiples of 16 feet, and are 100 feet deep. There are a variety of residential buildings-apartment buildings, row houses, and detached houses-usually mixed with businesses. Finally, there are alleys lined by garages and secondary buildings, such as carriage houses and studios.

All elements are planned around "the distance the average person will walk before thinking about getting in the car," says Michael D. Watkins, Kentlands' town architect in DPZ's Gaithersburg office. That's a maximum 5-minute walk-a quarter mile or 1,350 feet-from a town center to its edges.

New urbanists maintain that a family will need fewer cars. Duany likes to point out that it costs an average of $5,500 per year to support each car, the equivalent of the annual payment on a $55,000 mortgage.

Sidewalks are usually 5 feet wide instead of 4. Streets, designed to entice, not intimidate, walkers, are typically laid out in a hierarchical, modified grid pattern. The broadest are 36 feet wide; the narrowest, 20 feet. On-street parking is encouraged and counted toward minimum requirements. Vehicle speed is 15 to 20 mph, not 25 to 30 mph. Curb return radii are minimized so that a pedestrian crossing is not daunting. Superhighways are relegated to the far outskirts of town.

In a grid, traffic is designed to move more slowly, but it is also more evenly distributed so there are fewer and shorter duration jams, says Duany. In the typical suburb, broad commercial streets, called collectors, have become wall-to-wall traffic, while loop and cul-de-sac asphalt typically remains under-used.

Berkus objects to the grid, except to organize the town center. The "edges should be organic" for those who perceive "enclaves" as safer and more secure places to live, he says. Bernardo Fort-Brescia, principal of the Miami-based Arquitectonica, also thinks the undulating street and cul-de-sac should be offered. "There are no absolutes," he says.

|

25' Curb Return Radius 2-10' Travel Lanes with Parking Lane |

|

10' Curb Return Radius 2-10' Travel Lanes with 7' Parking Lane |

|

25' Curb Return Radius 2-10' Travel Lanes with 7' Parking Lane plus "Bump-out" |

Effects of curb return radii on pedestrian crossing distance. Source: Wilmapco, Mobility-Friendly Design Standards, Wilmington Area Planning Council, Nov. 1997.

The firm's plan for Meerhoven, a new town proposed for Holland, reflects many new urbanist concepts in a modern vernacular. "Nothing is faked to appear old," says Fort-Brescia. Every element has a function based on modern lifestyles. For example, the town lake is sized for triathlon swimming and perimeter marathon runs. But pedestrians and bikers are encouraged. And mass transit will whisk commuters to jobs elsewhere.

Retrofits are difficult, say new urbanists. Shopping centers are simplest because parking garages can replace surface lots. Mashpee Commons before and after. (Photo and caption, ENR , May 9, 1994.) |

Arquitectonica is fortunate-there are no intractable standards in the way of its plan. But in the United States, new urbanists say their biggest roadblocks are existing street design standards geared to traffic volume and efficient movement, and zoning that prohibits small lots and mixing building types. For example, firefighters and sanitation officials want to have a street wide enough for trucks to turn corners without crossing the centerline.

"Public works will view your proposal with suspicion" because in new urbanism, traffic is no longer the driving force behind street design, says Frank Spielberg, president of traffic engineer SG Associates Inc., Annandale, VA.

Spielberg, sympathetic to new urbanism, but cautious about traffic issues, says there are still questions: Lower expected traffic volume justifies narrow streets, but is actual traffic volume lower? How long would it take to convince residents they need fewer cars? Will traffic be retained within the project, which would relieve the developer of adjacent road upgrades?

Traffic engineers have been working for 40 years to accommodate the proposals of architects and planners, maintains Spielberg, chairman of the Washington-based Institute of Transportation Engineers'(ITE) 5- year-old committee on traffic engineering for neo-traditional development. Now that the approach is changing, "traffic engineers will respond," he says.

"Surprisingly, traffic engineers, the most recalcitrant of all, are the first to reform," agrees Duany. ITE plans to publish neo-traditional street design guidelines late this year or early in 1995.

In addition to ITE's manual, which already contains residential street guidelines, there are American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials standards. They support compact projects, "but only if you already know where to look," says C.E. Chellman, CEO of White Mountain Survey Co., a land surveyor-engineer in Ossippe, NH, and editor of ITE's draft guidelines.

Chellman says transportation officials often forget that ITE and AASHTO standards are not binding codes. Officials are reluctant to use judgment, he says.

Some engineers simply take issue with the specifics driving new urbanism. Skokie, IL-based traffic engineer Paul C. Box, who wrote the existing ITE residential street guidelines, claims lowering the speed limit is against human nature. He says onstreet parking is dangerous because children get hit running out between parked cars. He is against narrower through streets and the bicycle as transportation unless separate bike paths or lanes are constructed, which he says is too costly. He also thinks undulating sidewalks are safer than those along the street.

Until there is a body of research to support it, mainstream lenders and commercial interests will continue to shy away from new urbanism, says James Constantine, principal of Community Planning Research Inc., Princeton, NJ. In February, Constantine released data from a survey of "active" home-buyers attending the Home Builders Association of Memphis show at Harbor Town last September. Of 123, "a whopping two-thirds" said they'd "like" to live in a neo-traditional neighborhood, he says. The only market resistance was to small lots and minimal setbacks, he adds.

John H. Schleimer, president of Market Perspectives, Carmichael, CA, says even home-buyers surveyed recently who bought elsewhere "like" the idea of community and the option of walking places. But many said they paid the same price for bigger homes on larger lots.

Haymount's Clark isn't rattled: "Someone who wants to live on a mansion-size lot and 'commit cul-de-side' has to go elsewhere. That's why there is vanilla and chocolate."

By Nadine M. Post

Neo-traditional neighborhoods have begun to appeal both to community designers and home-buyers alike. It is important, however, to consider that neotraditional street design fundamentally differs from standard suburban street design. In recent years, many neighborhoods have been built across the country that claim to be neo-traditional that are, in fact, missing critical features.

The magazine article in this section provides a good overview of the concepts of neo-traditional neighborhood design. This section provides more specific details on neo-traditional street design, and explains how it is different from standard suburban street design.

Standard suburban street design is characterized by a hierarchical, tree-like pattern that proceeds from culde- sacs and local streets to collectors to wide arterials. The organization of the network collects and channels trips to higher capacity facilities. The use of streets in residential areas for inter-community and through-traffic is minimized by limiting access by constructing few perimeter intersections, reducing interconnections between streets, and by using curving streets and cul-de-sacs in the development. Where this layout is successfully designed and constructed, automobiles are the most convenient choice for short, as well as long, trips. The street layout forces longer, less direct auto travel when street connections are missing.

Typical suburban neighborhoods offer few route choices for trips. |

The hierarchical street layout reflects the guiding principle that streets on which residences front should serve the least traffic possible. At best, only vehicles traveling to or from the homes on a given street would ever appear on that street. There would be little or no "through-traffic," hence the prevalence of cul-de-sacs. Traffic from residential streets is quickly channeled through the street hierarchy to collectors and then to arterials. Only arterials, fronted primarily by stores, offices, or apartments, provide direct connectivity between land uses and other neighborhoods.

By contrast, Neo-Traditional Neighborhood Design (NTND) calls for an interconnected network of streets and sidewalks to disperse vehicular trips and to make humanpowered modes of travel (such as walking and biking) practical, safe, and attractive for short trips. Motorists, pedestrians, and public officials will find the regular pattern more understandable.

The street pattern in an NTND can also have a hierarchy, with some roadways designed to carry greater traffic volumes. A basic assumption of NTND planning, however, is that neighborhood streets that serve local residential trips can also safely serve other neighborhood trips and some through-traffic. For example, a street with 40 homes would need to carry about 20 vehicle trips during the peak hour. The effective capacity of this street could easily be 200 vehicles per hour without a significant effect on safety or environmental quality. By limiting the access to the street as in standard suburban design, 90 percent of its effective capacity is wasted. Nearby arterials must make up the difference.

By eliminating dead ends and designing all streets to be interconnected, neo-traditional neighborhoods provide multiple route choices for trips. By using narrow streets and by constructing more of them, more, yet smaller, intersections are created. In concept, therefore, overall network capacity is increased, traffic is dispersed, and congestion is reduced in neo-traditional communities. While this rationale seems intuitively correct, it must be carefully applied. Land use and density are not constant across a neo-traditional community. Larger traffic generators will attract larger numbers of vehicles that may require multi-lane streets and intersections.

Planners discourage alleys in standard suburban residential areas. In a typical suburban development, an alley behind homes serves no function because garages and their driveways are accessed from the street.

However, in Neo-Traditional Neighborhood Design, alleys give neighborhood planners design flexibility by permitting narrow lots with fewer driveways on local streets. Fewer driveways also mean more affordable, smaller home sites and more space for onstreet parking, especially if the home-owners use the alleys for their own vehicular access, parking, and utilitarian activities. Alleys provide space for underground or unattractive overhead utilities while freeing streets for trees and other plantings. Alleys also can be used for trash storage and collection and emergency vehicle access. NTND projects do not have alleys everywhere, but where they do, traffic safety may improve. Alleys eliminate residential driveways and the need for backing up onto the street, which would otherwise occur and is inherently unsafe.

Design speeds for suburban neighborhood streets range from a minimum of 25 or 30 mph to 45 mph. The design speed recognizes the type of facility (local, collector, or arterial), and it allows for a standard 5- or 10-mph "margin of safety" above the 85th percentile speed, which is usually the posted speed. Often, the signing of wide streets for 25 to 35 mph simply results in more speed violations. It is not unusual for neighbors to complain of speeding traffic on neighborhood streets and to request actions to slow the traffic. Stop signs, speed bumps, "Children at Play" signs, and the like may have to be used to slow vehicles from the original design speed of the street.

Neo-traditional neighborhoods have narrower, tree-lined streets. |

Neo-Traditional Neighborhood Design projects attempt to control vehicle speeds through careful design of streets and the streetscape. Minimum NTND street design speeds are 15 to 20 mph. Onstreet parking, narrow street widths, and special design treatments help induce drivers to stay within the speed limits. T-intersections, interesting routes with lots of pedestrian activity, variable cross-section designs, rotaries, landscaped medians, flare-outs, and other treatments may be used.

At slower speeds, the frequency of vehicular accidents may decline, and those that do occur may be less severe. What is not clear is whether or not the frequency of pedestrian-vehicle accidents also decreases with speed. Indeed, more than 70 percent of all pedestrian traffic collisions occur in locations where speeds may be low (NHTSA, 1989). Pedestrian accident types are often associated with darting out from between parked cars, walking along roadways, crossing multi-lane intersections, crossing turn lanes, dashing across intersections, backing-up vehicles, ice cream vending trucks, and bus stops.

For NTND projects, the goal is to create more "active" streetscapes, involving more of the factors that slow drivers. These include parked cars; narrow street width; and eye contact between pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers. The overall impact of these elements of design is enhancement of the mutual awareness of drivers and pedestrians. Thus, many professionals believe that in a neo-traditional neighborhood, drivers are more likely to expect pedestrians and avoid them in emergency situations.

Neo-traditional neighborhoods re-create commercial densities reminiscent to pre- World War II era downtowns. |

Street Width

In suburban neighborhoods, street type, width, and design speed are based

on projected vehicle volumes and types. The larger the vehicle permitted on

the street according to local regulations, the wider the street. The focus is

on motorized vehicles, often to the exclusion of pedestrians, other transportation

modes such as bicycles, and other considerations of the community environment.

Ideal suburban lane widths per direction are 12 feet, while exclusive turn lanes may be 10 feet or less. Depending on whether or not parking is permitted, two-lane local street widths vary from 22 to 36 feet, while two-lane collector streets vary from 36 to 40 feet. In many suburban jurisdictions, the minimum street width must accommodate cars parked on both sides, an emergency vehicle with its outriggers, and one open travel lane. These "possible uses" instead of "reasonably expected uses" lead to a worst-case design scenario, an excessively wide street, and probable higher travel speeds.

In contrast to suburban street design, the width of NTND streets is determined by the projected volumes and types of all the users of the street, including pedestrians. The actual users of the street and their frequency of use help determine street width. In addition, NTND-type standards come into play. The basic residential NTND street has two lanes, one for each direction, and space for parking on at least one side. The resulting minimum width may be as narrow as 28 to 30 feet. Design considerations, however, may preclude parking in some areas, perhaps to provide space for bicyclists.

If neo-traditional communities encourage narrower streets with parking, then vehicles will naturally slow and stop for parking maneuvers and for larger approaching or turning vehicles that may encroach on the other lane. The NTND concept is that drivers must be more watchful (as they usually are in central business district (CBD) areas) and, once more watchful, drivers expect to and do stop more frequently.

To alert drivers to the relative change in importance between vehicles and pedestrians, they must be warned at entrances to the NTND. This warning must be more than signs. Narrower streets; buildings closer to the street; parked cars; smaller signs;and the generally smaller, much greater visual detail of a pedestrian-scale streetscape all serve as good notice to the visitor.

Curb radii in suburban neighborhoods match expected vehicle type, turning radius, and speed to help ensure in-lane turning movements if possible. In order to accommodate the right-hand turning movements of a tractor trailer (WB 40) and larger vehicles, no matter what their frequency of street use, suburban streets typically have minimum intersection curb radii of 25 to 35 feet. Some jurisdictions require 50 feet or more. What such large curb radii do for smaller, more predominant vehicles is to encourage rolling stops and higher turning speeds. These conditions increase the hazards for crossing pedestrians. The large curb radii effectively increase the width of the street, the pedestrian crossing time, and the exposure of pedestrians to vehicles.

NTND curb radii are usually in the range of 10 to 15 feet. They depend on the types of vehicles that most often use the street, not the largest expected vehicle. The impacts on pedestrians, parking spaces, and turning space for larger vehicles are also considered. The smaller the curb radii, the less exposure a crossing pedestrian has. Furthermore, an additional parking space or two may extend toward the intersection with small curb radii, or if parking is prohibited, additional room for turning vehicles is created.

Many manuals detail conventional intersection design and analysis for suburban developments (AASHTO, 1990). Such intersections are designed for an environment in which the automobile is dominant. Hence, traffic engineers attempt to maximize intersection capacity, vehicle speed, and safety. They also aim to minimize vehicle delay and construction cost. As a result of the hierarchical approach to street system design, which carries traffic from narrow local streets to larger collectors and arterials, intersection size and complexity grow with the streets they serve. Drivers of these streets expect an ordered structure and any anomalous designs present safety problems.

In Neo-Traditional Neighborhood Design, the concept of connected patterns of narrow, welldesigned streets is intended to improve community access in spite of low design speeds. The numerous streets provide more route choices to destinations and tend to disperse traffic. In concept, the more numerous, smaller streets also mean smaller, more numerous, less congested intersections. Again, due to slower vehicular speeds, greater driver awareness, and the desire for vista terminations, some NTND intersection designs are typically different from suburban designs.

Trees and landscaping form an essential element of the streetscape in NTND projects. |

Street Trees and Landscaping

Subdivision standards and roadway design practice strictly control the size

and location of street trees and other plantings. Some local regulations may

even prohibit trees and other plantings near the street. These guidelines originated

with the precedent of the "forgiving roadway" that arose through tort

actions. They generally place trees far from the edge of highspeed roads to

reduce the chance of serious accidents if vehicles swerve off the road. For

suburban streets with lower design speeds and space for parked cars, trees can

be closer to the street.

Trees and landscaping form an essential element of the streetscape in NTND projects. The relationship of vertical height to horizontal width of the street is an important part of creating a properly configured space or "outdoor room." On some streets that feature single-family housing, the design may call for setting the houses back somewhat from the street. In neighborhoods and along streets such as this, the trees form an important part of that street. While providing shade and lowering street and sidewalk temperatures, they create a sense of closure in a vertical plane. Along streets that contain townhouses and stores with apartments above them, actual full-sized trees become less important, while smaller trees and landscaping remain essential elements.

Suburban neighborhood design calls for large, efficient luminaires on high poles spaced at relatively large distances. Their purpose is not only to illuminate the nighttime street for safer vehicle operation, but also to improve pedestrian and neighborhood security.

Street lighting in traditional neighborhoods serves the same purposes as that in suburban neighborhoods. However, the intensity and location of the lights are on a more pedestrian scale. Smaller, less intense lumninaires are often less obtrusive to adjacent properties and allow the nighttime sky to be seen. They only illuminate the streetscape as intended.

Sidewalks in suburban neighborhoods typically have a minimum width of four feet. While they may lie parallel to the street, they may also meander within the right-of-way or lie entirely outside of it.

NTND designers try to keep walking as convenient as possible, and this results in shorter distances when sidewalks remain parallel to the street. The focus is on a safe and pleasant walking experience. The typical minimum sidewalk width is 5 feet because this distance allows two pedestrians to comfortably walk side-by-side. Walking distances should be kept as short as possible, and, in traditional neighborhoods, horizontally meandering or vertically undulating designs are avoided even though these features may add interest. Neither should a pedestrian route be perceived as longer than the same driving route, nor should it create undue mobility problems for visually impaired pedestrians or people who use wheelchairs.

Conventional front setbacks are 15 feet or more for several reasons. Setbacks allow road widening without having to take a building and compensating its owner. They help sunlight reach buildings and air to circulate. In addition, side and rear setbacks afford access by public safety officials.

Traditional designs have no minimum setback and, indeed, maximums may be specified by some policymakers. The goal is to integrate residential activity and street activity and, for example, to allow the opportunity for passers-by to greet neighbors on their front porches. Furthermore, the walls of nearby buildings help to vertically frame the street, an important aesthetic dimension.

Pedestrian push buttons should be conveniently placed. Be sure existing site features are not obstacles to reaching the button. |

NTND projects are intensely planned and closely regulated as to types and ranges of use and location. Such planning affords the otherwise unusual opportunity to have a good degree of understanding about the future traffic demands for a street, and to design for those needs. Furthermore, to minimize the need for future widening, NTND streets have adequate rights-of-way, typically not too dissimilar to "standard" requirements, and the buildings do not encroach on the right-of-way. Within the right-of-way, the typical NTND street will have a planting strip of 6 feet or so on each side, and parking lanes on both sides of the street (sometimes striped, sometimes unstriped), both of which provide opportunities for some widening without a great deal of effort if a future wider street is needed.

The importance of parking for suburban projects cannot be over-emphasized because nearly all trips are by car. Off-street parking is preferred; indeed, large parking lots immediately adjacent to the street give a certain status to retail and commercial establishments. Sometimes, suburban parking is allowed on the street in front of smaller stores. Because of the importance of vehicle access in suburban development, city ordinances typically establish minimum parking criteria.

Suburban parking lots in retail developments are vast-and are rarely full. |

Neo-traditional design encourages on-street parking by counting the spaces toward maximum parking space requirements. The parking is usually no more than one layer deep. If the adjacent development contains residential and other uses, parallel parking is recommended. In commercial areas, 90-degree head-in and diagonal parking are permitted. Parking lots are usually built behind stores. As a result, the street front is not interrupted by a broad parking area.

On-street parking is a concern for some traffic engineers. The concern is that "dart-out" accidents (where pedestrians, especially children, dart-out from between parked vehicles into the traffic stream) will increase if on-street parking is encouraged. The proponents of NTND projects argue that a row of parked vehicles enhances pedestrian activity by creating a buffer between pedestrians and moving traffic, that the overall street design slows moving traffic so that any accidents that do occur are less severe, and that the active streetscape makes drivers more alert to pedestrians. There is also some evidence that children in conventional neighborhoods are susceptible to driveway backing accidents. Onstreet parking, therefore, must be limited to streets where the design fosters low speeds (20 mph or less) for moving traffic.

Text and graphics for this lesson were taken from the following sources:

Institute of Transportation Engineers, Neo-Traditional Neighborhood Street Design , 1995.

Nadine M. Post, "Putting Brakes on Suburban Sprawl," Engineering News Record , May 9, 1994, pp. 32-39.

Wilmington (DE) Area Planning Council, Wilmapco Mobility-Friendly Design Standards , Nov. 1997.

For more information on this topic, refer to:

Office of Transportation Engineering and Development, Pedestrian Design Guidelines Notebook , Portland, OR, 1997.

"Made to Measure: How to Design a Livable Street the New England Way," Planning Magazine , June 1996.

Town of Cornelius, NC, Land Development Code, Traditional Neighborhood District , 1996.

| < Previous | Table of Content | Next > |